Alaska Fish & Wildlife News

May 2021

Hair Snares “Trap” Grizzly Bears

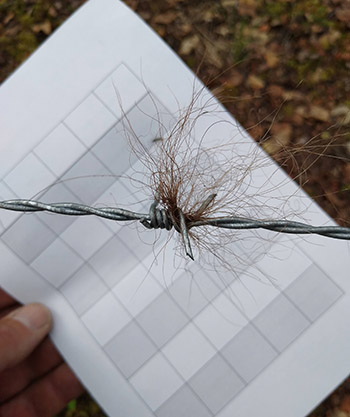

Biologists with the Alaska Department of Fish and Game will be setting about 100 hair snares for bears in Southcentral Alaska’s Game Management Unit (GMU) 13 this summer. These “hair traps” use strands of barbed wire to snag tufts of fur and don’t capture or restrain the bears. DNA in the hair follicle provides valuable biological information about the bears.

“Our goal is to get an abundance estimate, to learn how many grizzly bears are on the landscape,” said wildlife biologist Christi Heun.

It’s a landscape the size of West Virginia – just over 23,000 mi2 (about 62,000 km2). GMU 13 contains the Nelchina Basin and is surrounded by the Talkeetna, Chugach, Wrangell, and Alaska mountain ranges. Denali National Park is on the northwest side, with the Parks Highway on the west and the Glenn Highway on the east. An important area for moose hunting, it is home to the Nelchina Caribou Herd.

It is also part of the traditional homeland of the Ahtna, an Alaska Native Athabaskan people who call it Atna Nenn. Ahtna, inc., an Alaska Native regional corporation based in Glennallen, is a collaborator in the project as is AITRC (Ahtna InterTribal Resources Commission), which helps manage the fish, wildlife, and plant resources in the Ahtna Traditional Use Area.

“We’ve been really lucky to collaborate with some fantastic organizations on this project,” Heun said. Sterling Spilinek with AITRC and Trenton Culp with Ahtna are helping with field logistics. Heun said without these collaborators, this project could not be successful. Shawn Crimmins with the Alaska Cooperative Fish and Wildlife Research Unit at the Institute of Arctic Biology in Fairbanks is also collaborating.

Snagging Bears

Hair snaring provides information that used to require physically capturing animals. Hair snaring is favored as an economical, non-invasive way to collect a tiny tissue sample. DNA in the follicle of the hair identifies individual bears, the sex of the animal, and its relatedness to other bears; repeated detections of individuals can be used with statistical models to address a variety of questions about a population including abundance, density, and population growth rates. Grizzly bears are the focus, although there are plenty of black bears in the area that may be sampled as well.

That sample identifies the animal, essentially marking it as an individual. Over the course of the summer, as bears are “captured” and “marked” – and some are “recaptured,” Heun, biologist Jeff Stetz, and their colleagues will be able to estimate the number of grizzly bears in the area.

Wildlife biologist Nick Demma studies carnivores and has been working on Unit 13 grizzly bears. He’s equipped some females with GPS collars, which provide insights into their movements and home ranges. This has already proved valuable to this project. The opportunity to conduct concurrent research on this population will not only improve the quality of results from each method but will lead to improving how populations are monitored into the future.

“The collared bears helped guide our study design,” Heun said. “Using his information, we can look at the average home range size of the females and use the estimate to help set how far apart the traps should be. And we’ll compare what he’s learning with what we find. We can use his information to fortify our information.”

Stetz and Heun are fine-tuning the trap design this spring with a couple prototypes at the Alaska Wildlife Conservation Center near Girdwood. AWCC has long collaborated with Fish and Game; the 200-acre site is home to six bears and a variety of other wildlife and was a partner in the Wood Bison reintroduction project.

Heun noted that once the study design is finalized, this process could be substantially less expensive than the traditional wildlife research methods for estimating bear abundance, which involve a lot of air support and expensive radio and GPS collars. These methods have the added benefit of not requiring biologists to handle the animals, which requires chemical immobilization and being fitted with a collar. Beyond safety concerns for wildlife and biologists, limiting the effects on study animals simply makes for good science.

Stetz drew from recent work in the Yukon by Canadian carnivore biologist Jodie Pongracz. She did a study using free-standing, three-legged “teepee traps,” with barbed wire wrapped around the posts. A debris pile in the center mimics a bear cache. Instead of bait, scent attractants are used to draw bears to the sets.

“They were wildly successful,” Heun said. “They got so much information and great footage of the bears from trail cameras.”

Stetz and Heun conducted a pilot study in GMU 13 last summer with about 60 sites in five or six clusters. “We were testing the methods, checking the logistics regarding the work involved,” she said. It was a lot of work. “If you weren’t in the field you were getting ready to go out into the field.”

Some traps won’t use the newer constructed-structure design but will the take advantage of local vegetation. Heun described it as “the old tried and true string-a-barbed-wire-between-the-trees-and-leave-a-giant-pile-with-scent-in-it technique.” Anise, castor, skunk, or cherry broadcast a far-reaching scent; about a gallon of cow’s blood (sourced from a local slaughterhouse) poured on the brush pile gets bears up next to the wire.

“There is no actual bait, just strong odor that will draw them in,” Heun said. “There is no actual reward for going to these traps.” As such, bears do not defend the lure and do not become food-conditioned.

Hair snared on the barbs is carefully pulled off with tweezers, placed in a sample container, then a lighter is used to burn and sterilize the barbs so a new sample can be captured. Each site will be visited every two weeks, five times over the summer – about 500 total site visits.

“Field crews consist of two people, and there are four or five crews,” Heun said. “It’ll be almost constant work rotating through the sites. There will be some hiking in, and some we’ll boat in, and some we’ll take ATVs in. We’re hoping to get some air support for one of the remote clusters.”

They’ll begin setting up the hair trap sites about June 1 and traps will remain in the field until mid-August. As soon as it is set up it will begin “working.” Heun said after a site is checked it will be moved a little bit.

“Maybe even as little as few hundred feet, it keeps the bears interested,” she said. “Sometimes bears will roll in the brush scent piles; by moving the site you eliminate uncertainty about hairs around the site. For the sites where we’ve strung barbed wire around trees, we’ll just unwrap them and move them over to some new trees.”

They also change the type of scent, since once a bear has investigated a site and learned there’s no actual food there, they want to rekindle its interest to draw it back. These sites aren’t like garbage piles where bears would hang around, scavenging.

“If someone comes across one of these sites, we want people to know what they are,” she added. “If you happened to stumble upon a trap, please leave the area immediately, without disturbing the site, and be sure to make a lot of noise to alert bears that may be in the vicinity. Bears tend to investigate for a few minutes then take off as there is no food reward associated with the scent. I personally have never seen a bear while I was checking a trap, but you should always remember to be bear aware regardless of where you are in the outdoors.”

More on Alaska's brown (grizzly) bears

Subscribe to be notified about new issues

Receive a monthly notice about new issues and articles.