Alaska Fish & Wildlife News

December 2018

Goin’ with the Flow

The Instream Flow Program Protects Fish Habitat

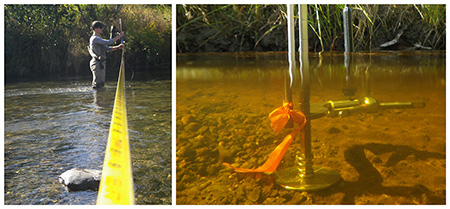

“Four point five four at twelve point five!” I yelled.

“Four point nine four?” came back from the stream bank.

“No, four point FIVE four!”

What was I doing standing in Granite Creek, a glacially-fed river east of Palmer for nearly an hour, yelling numbers to Leah over the roar of the water? Not only was the fast-moving water testing my balance, but (now that it was October) the water temperature hovered right above freezing. We were working to protect fish and wildlife habitat, of course!

Protecting Alaska’s Rivers and Lakes

From the unmatched sockeye salmon runs in Bristol Bay to the well-fed coastal brown bears in southeast, Alaskan waters produce some of the most viable fish and wildlife populations in the world. In addition to sustaining fish and wildlife, humans value the waters of Alaska for many reasons including hydroelectric power, drinking water, navigation, recreation, and aesthetics. It is the mission of Alaska Department of Fish and Game’s (ADF&G) Instream Flow Program to protect Alaska’s rivers and lakes by ensuring that our robust fish and wildlife populations will have sufficient amounts of good quality water in their habitat. The Instream Flow Program uses rigorous scientific techniques to conduct hydrologic investigations to determine the instream flows required to maintain healthy conditions for aquatic and riparian species, such as salmon and aquatic insects, as well as terrestrial (land) species such as moose and bear or migratory birds. The anticipated result of these investigations is a “Reservation of Water” which is the legal protection of instream flows for fish and wildlife habitat, migration, and propagation, such as salmon spawning habitat.

What is Instream Flow?

Instream flow is simply the amount of water flowing in a stream or the volume of water in a lake at any given time of year. Fish and other aquatic and terrestrial species have adapted to natural streamflows and lake levels that provide essential seasonal habitats used by many different species during their various life stages. A great example is how these ranges of natural stream flows play a vital role in creating and maintaining instream habitat that fish, such as salmon, depend on to meet their spawning, rearing, incubation, overwintering, and migration requirements.

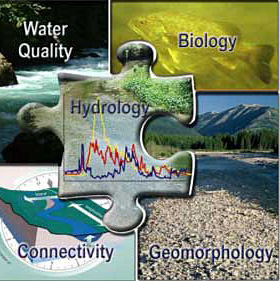

The structure and function of river and lake systems are based on five components: hydrology, geomorphology, biology, water quality, and connectivity. Hydrology is the study of water movement and its properties, and this may be the main component that comes to mind when we think about water resources management. However, when considering fish and wildlife habitat requirements on the watershed level (that is, a system of rivers, lakes, and wetlands confined to a basin), it is important to note that all five components and their interactions with each other must be assessed to provide a holistic characterization of rivers and lakes to aid in managing aquatic ecosystems.

Quantifying Streamflow and Lake Levels

Instream flow levels are calculated through scientific studies referred to as hydrologic investigations. Reliable streamflow measurements are essential to determine how much water is needed to sustain productive fish habitat within a watershed. Streamflow measurements (aka discharge measurements) record the amount of a water flowing in a stream or river at a point in time, usually expressed in cubic feet per second (cfs), and are a critical component of every hydrologic investigation. It is important to quantify stream discharge at different times throughout the year because water levels can fluctuate significantly between seasons.

The streamflow data collected needs to be scientifically defensible, credible, and comparable. To accomplish this, scientists within the department’s Instream Flow Program use several different types of equipment to collect discharge measurements depending on environmental conditions and the physical characteristics of a stream or river.

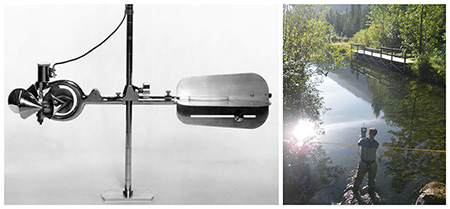

In shallow, low-velocity streams that can be safely waded, scientists can use two types of meters attached to a rod to collect a stream discharge measurement. One instrument that was the standard until the recent decade is a mechanical meter, known as the Price AA Current Meter, which has conical cups that rotate when placed in the flow of water to record velocity. Advancements in acoustic technology have led to a new standard type of equipment used for discharge measurements. Today, the meter type that our Instream Flow Program most frequently uses is called an Acoustic Doppler Velocimeter (ADV). This instrument measures the water velocity by transmitting sound waves which bounce off particles suspended in the moving water.

When performing a discharge measurement, the field methods for both meter types are similar. Essentially, one scientist moves slowly across a river transect, collecting 40-second velocity measurements at specific depths at approximately 25 locations. At the completion of a transect, the water discharge rate is calculated by a mathematical equation (velocity multiplied by the cross-sectional area).

For larger streams, our Instream Flow Program utilizes a more advanced technology known as an Acoustic Doppler Current Profiler (ADCP), which is deployed on a tethered or remote-controlled boat. The advantage of using an ADCP is that it collects a lot more data, delivering a complete stream profile with velocity measurements throughout the entire depth of the water column vs. individual measurements at specific depths obtained when using the methods described above.

Why is an Instream Flow analysis important?

Instream flow analysis includes the concept that a range of varying water flows and levels throughout the year, not a static amount, is necessary for aquatic ecosystems to function properly. For example, fish require differing amounts of water depending on their life stage, from higher flows that promote upriver migration during the summer to lesser flows needed for protection of eggs in the winter. Once the hydrological data has been collected and analyzed together with the stream’s biological data, scientists use the information to determine how much water should be requested to remain in the stream for habitat protection, with consideration to the amount that may be available for other out-of-stream uses. Based on this information, a Reservation of Water application is then prepared and submitted to the Alaska Department of Natural Resources (DNR), the agency which acts as the water manager for the State of Alaska. The resulting Reservation of Water is a legal document that grants instream flow water rights for the purpose of sustaining fish and wildlife habitat. Since 1984, ADF&G has filed more than 300 reservation applications resulting in protection of more than 2,000 miles of rivers (and several lakes). However, with over three million lakes and more than 12,000 rivers in Alaska, much work remains.

For Additional Information:

Please visit the ADF&G Instream Flow Program webpage for further information:

Ann Marie Larquier and Leah Ellis are both habitat biologists with the Instream Flow Program based in Anchorage. They enjoy long field days wading through rivers across the state, even if it means frozen toes.

Subscribe to be notified about new issues

Receive a monthly notice about new issues and articles.