Alaska Fish & Wildlife News

November 2017

Snowy Owl

Arctic Raptors Can Be Wide-Ranging Nomads

A duck hunter on the Mendenhall Wetlands in Juneau found an unexpected bird in late October, a snowy owl. These Arctic raptors are rare in the Juneau area, which is well outside their normal range.

Don Martin was crossing the wetlands in the foggy pre-dawn light when he noticed a white thing in the grass. “At first I thought it was a snow goose, or a seagull or something, but when we got closer it was obvious what it was,” he said. Martin, who works with the Forest Service, has degrees in wildlife management and fisheries, but it doesn’t take a biologist to recognize a snowy owl.

“It ran, with its wings stretched out, but it couldn’t fly and it didn’t go far,” he said. “It was apparent that its wings were okay, and all the feathers were there, but it couldn’t fly. It looked wet but I didn’t put my hands on it.”

Martin’s hunting spot was within sight of the owl. “I kept an eye on it, I was thinking I might need to scare an eagle off it,” he said. “A northern harrier did fly over it and take a second look, but it left it alone.”

It was foggy and hunting was slow, so after a couple hours he called the Juneau Raptor Center. He was advised to catch the bird and someone would meet him in the parking lot. He threw his jacket over the owl and carefully wrapped it up with its head sticking out. On the trail out he ran into a group of birders led by another biologist, Mark Schwann, and they were pretty excited to see the owl.

Martin said he’s seen other raptors on the wetlands, including osprey, short-eared owls and a peregrine falcon, but never a snowy owl. Eagles are abundant, and many area duck hunters (or their dogs) have lost a race to a downed bird to those sharp-eyed opportunists.

Snowy owl sightings outside the Arctic are usually associated with irruption events. Raptors found in Interior Alaska or the Arctic, such as goshawks, rough-legged hawks, great grey owls and snowy owls leave the north if lemmings and the other small mammals they depend on for food become scarce. These movements are called irruptions; they’re not migrations because they are irregular and driven by food. Lemmings are a dietary staple for snowy owls, and their populations fluctuate. When lemming numbers are down in an area, snowy owls don’t breed or nest there. Some winters, large numbers of snowy owls appear well outside their normal range, making dramatic appearances in places like Pennsylvania and Washington.

Steve Lewis is a raptor biologist with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, based in Juneau. He said the established thought about irruption fits well for raptors like great grey owls or short-eared owls, but biologists have learned a lot more about snowy owls in recent years, and there is more to the irruption story than food. That’s especially true this year, since it seems food is abundant.

“It’s been a good year for small mammals in the Interior,” he said. “I was in Fairbanks last week, and it’s been pretty warm and wet in Fairbanks. Normally it should be dry and snowy. There is vole sign all over, and it’s a big year for hares.”

He said someone in Fairbanks saw a snowy owl last week, which is unusual even for Fairbanks.

Lots of small mammals in the Arctic can mean high nesting success for snowy owls. “They can have broods of five to seven, and they breed more when there is a lot of food,” he said. “It’s probably a big year for owls and there’s an abundance of owls.”

That said, he added that it’s also not simply dispersal, where a young adult animal strikes out to find its own home range or territory, because a snowy owl might leave the area where it was hatched and raised, and then return a year later. Biologists are learning that there are extreme events in some years where great numbers of snowy owls leave the Arctic. There was a huge irruption the winter of 2013-2014, he said, and snowy owls were in the Great Lakes region, the Eastern US and Canada, and as far south as Florida.

“The classic thought is that a raptor is in a place, its territory, and they breed if there is enough food, and they don’t if there is not enough. It’s more complicated for snowy owls. They’re nomadic. They move until they find food. It’s not like lemmings go down all across the Arctic. Snowy owls will move until they find the right conditions.”

He said one marked snowy owl spent one season in Barrow, the next in Russia, and the following year in Canada.

He said Juneau is not a good place for a snowy owl, and in the past, snowy owl sightings have been followed by people finding a dead owl. “It’s really wet here, and there are not a lot of small mammals here compared to other areas,” he said.

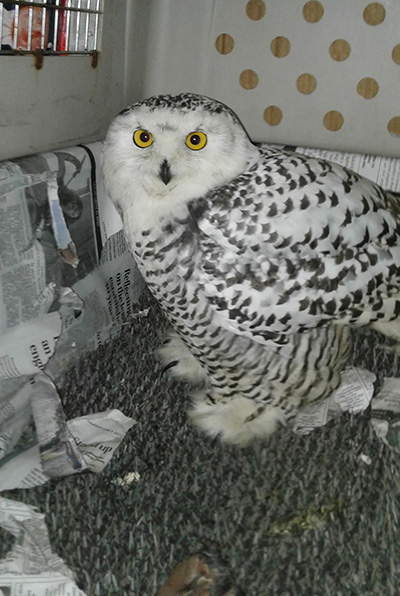

Janet Capito, with the Juneau Raptor Center, examined the owl when it was brought in. “He was soaking wet and looked pitiful. He was not owl-like in any way, he wasn’t aggressive, he didn’t try to bite, which is unusual. I could move all the different parts and he didn’t try and draw back or anything. Nothing seemed broken, he was exhausted and drenched. One thing I found was that he was very thin.”

Capito said the snowy owl was slightly larger than a great horned owl, with feathered feet. She did not have a sense for its age. They administered fluids and warmed it up, and the next day it was much stronger.

“What a difference,” Capito said. “I have high hopes for this guy. He was far more aggressive and more normal. I’m not sure what happened, maybe the leftover Typhoon Lan just soaked him.”

Juneau and much of northern Southeast Alaska was hit by a powerful rainstorm just two days earlier, the remnant of an Asian typhoon that dumped up to six inches of rain in some areas, with high winds.

The snowy owl was flown to Sitka the following day. Capito said the Alaska Raptor Center there has a vet who deals with a lot of birds, and is a larger facility better equipped to deal with a raptor the size of a snowy owl.

Capito has been with the Juneau Raptor Center 23 years. “This is maybe the fourth or fifth snowy, we don’t get very many,” she said. “We get a variety of owls, from little saw whets and northern pygmy owls, up to great horned owls.”

Veterinarian Victoria Vosburg has a clinic in Sitka, Pet’s Choice Veterinary Hospital, and also works closely with the Alaska Raptor Center. She said working with ARC, she sees about 200 birds a year.

“That’s all birds, we don’t just take raptors,” she said. “We see about ten owls a year, mostly western screech owls. They seem to be very abundant on our island in particular.”

Vosburg and technician Jennifer Cedarleaf examined the snowy owl. Cedarleaf thinks it is a juvenile female, hatched this spring. Vosburg said the bird is very thin, dehydrated, and hypothermic. “It should be up around 106 or 108, and it’s at 98.4,” she said. “Birds are much warmer than mammals.”

The owl was having difficulty breathing, so they did not finish the examination, which would’ve included an x-ray to identify potential injuries. Instead, they began providing oxygen via a cone that fits over its beak. No injuries were noted, but they did not do a full examination.

She said the Alaska Raptor Center has rehabilitated and released three snowy owls in the past. The birds were not released on Baranof Island, but were instead flown back up to the Arctic for release.

“We released two in Barrow and one in Prudhoe Bay,” she said.

More on winter 2014-15 snowy owl irruptions: eBird (Cornell University and Audubon) article

Riley Woodford produces the SoundsWild! radio program in Alaska. He studied barn owls in Eastern Oregon and worked with spotted owls in Arizona.

Subscribe to be notified about new issues

Receive a monthly notice about new issues and articles.