Alaska Fish & Wildlife News

August 2017

Watching for Ticks

Ticks, small blood-sucking arachnid parasites, are not well-known in Alaska. One species, generally found on squirrels and hares, is fairly common and native to the state, but those aren’t the problem. It’s the introduction of non-native, potentially disease carrying ticks that’s a concern.

Kimberlee Beckmen, a wildlife veterinarian with the Alaska Department of Fish and Game, is working with state veterinarian Bob Gerlach and other researchers to study and monitor the introduction of non-native ticks to Alaska. They are asking the public to send them ticks that are discovered on pets, people and game animals.

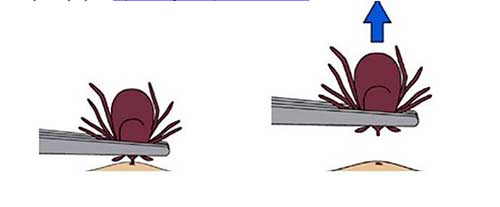

If you find a tick on your pet, you can remove it yourself or take your pet to a veterinarian. It’s easy to remove a tick. You don’t need to torture ticks with solvents or heat (heat causes the tick to regurgitate material back into the wound and should be avoided). Use fine pointed tweezers, grasp the tick close to the skin, apply firm, steady tension straight out and in just a few seconds, it will release. Don’t squash it. Any fluids released are infective too so you don’t want to get any of the fluid in a cut or on your skin. Wash up afterward.

Put the tick in a small unbreakable container. It is best if it is in a small amount of ethanol (vodka works in a pinch) but not rubbing alcohol. It can also be sent by itself in an unbreakable container, with no wadding or tissue because that dries it out.

It is critical that some information is provided as well. You can download a “sample submission form” from the Fish and Game website. This form is used for a wide variety of samples – so note on the form this is a tick submission. Researchers need to know the host animal or if the tick was on a person, the location where the tick was found, and your contact information.

State Veterinarian Bob Gerlach is with the Department of Environmental Conservation. He’s based in Anchorage, and Beckmen is based in Fairbanks. The samples from pets or people can be sent to Anchorage and ticks found on wildlife should be sent to Fairbanks. They will then be sent to Georgia, where an expert is identifying the tick species.

Gerlach said he’s seen more tick samples this year than ever before. “I sent off six last week, and I got 10 in this week.”

In the past, Beckmen was not collecting Alaska’s native squirrel ticks, but Gerlach said he’ll take any tick samples. Researchers with the University of Alaska Fairbanks are testing native ticks for potential tick-borne diseases like tularemia.

“There were two cats in Fairbanks that died, and tularemia was suspected,” he said. The diagnosis was confirmed by Dr. Murphy, the pathologist at the UAF Veterinary School.

“Pets may move into Alaska with ticks they acquired from southern areas where tick-borne diseases like Lyme Disease, Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever, Anaplasmosis or Babesia are endemic,” Gerlach said. “Ticks from these animals can be spread to other pets or to wildlife, and then possibly people.”

A pet could potentially vector a tick-born disease to native ticks. “If a dog got a tick down south that was carrying something like Lyme disease, and came up here and was later bitten by a tick in Alaska, that tick could then carry and transmit the pathogen,” he said.

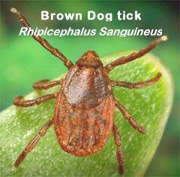

The sample submission process is already providing valuable insights. Over the past five years, Beckmen has received more than 80 samples, including the first non-native ticks seen in Alaska. They came up to Alaska on dogs and people, and were sent to her as samples. The tick species included the American dog tick, the brown dog tick and the Rocky Mountain wood tick.

Beckmen has published evidence that some non-native ticks are now established in the state. Both the brown dog tick Rhipicephalus sanguineus and the American dog tick Demacentor variabilis are established in the Fairbanks and North Pole area (also in Anchorage/Eagle River, Chugiak and Valdez). The brown dog tick prefers indoors, especially kennel environments and homes.

Our current climate can support the life cycle of many of these ticks, once they arrive, Beckmen said. “The only thing to prevent this is to keep them from arriving. People should look for ticks and treat their dogs with a tick repellant if they are coming up.”

Wildlife Health & Disease Surveillance Program Email: dfg.dwc.vet@alaska.gov

Wildlife Health Information Phone: 907-328-8354

Alaska State Veterinarian office: 5251 Dr. MLK Jr. Ave., Anchorage, AK 99507

State Wildlife Veterinarian address: 1300 College Road, Fairbanks, AK 99701

Submitting a sample Sample submission form

More on parasites in general

Subscribe to be notified about new issues

Receive a monthly notice about new issues and articles.