Alaska Fish & Wildlife News

May 2016

Alaska’s Private Non-Profit Hatchery Program

Alaska’s modern salmon fisheries enhancement program began in the early 1970s, when state harvests plummeted to record lows. The Alaska Department of Fish and Game took the early lead in salmon production and rehabilitation. Fish ladders were constructed to provide adult salmon access to previously non-utilized spawning and rearing areas. Lakes with waterfall outlets too high for adult salmon to ascend were stocked with salmon fry. Log jams were removed in streams to enable returning adults to reach spawning areas. Nursery lakes were fertilized to increase juvenile salmon growth. The state built new hatcheries to raise salmon.

Alaska lawmakers authorized private nonprofit corporations (PNP) to operate salmon hatcheries to rehabilitate the state's depressed salmon fishery in the mid-1970’s, after voters approved a constitutional amendment that allowed for limited entry to commercial fisheries and the efficient development of aquaculture in the state. The amendment allowed hatcheries to take broodstock – the adult salmon used to collect eggs and milt - from wild stocks for production and to sell a portion of their returns to pay for operations. Alaska lawmakers also established a revolving loan fund for hatchery construction and operations.

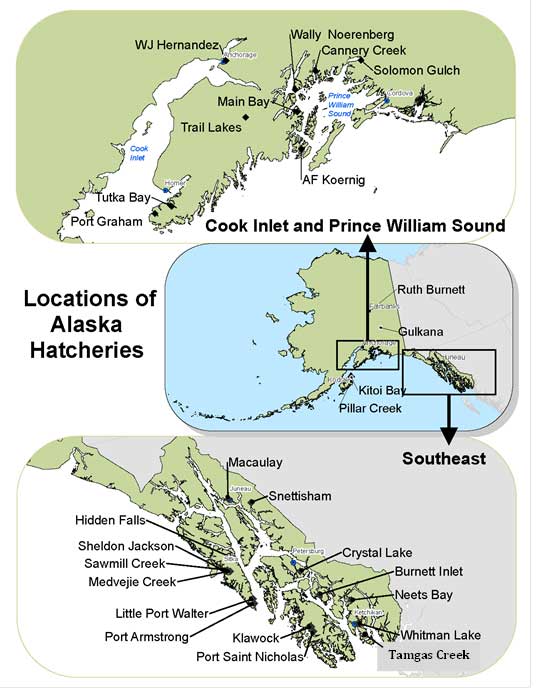

Commercial salmon fishermen in Southeast Alaska, Prince William Sound, Cook Inlet and Kodiak formed PNP regional aquaculture associations to operate hatcheries. Fishermen in these regions pay a self-imposed tax on their landings that help fund the operation of the associations. Other independent PNP corporations, such as the Valdez Fisheries Development Association, the Douglas Island Pink and Chum Corporation in Juneau, and Armstrong Keta, Inc. on south Baranof Island, also built and operate hatcheries.

Today, there are 25 hatcheries operated by PNP corporations. The State of Alaska also operates two sport fish hatcheries in Fairbanks and Anchorage that produce Chinook salmon, rainbow trout, coho salmon and Arctic char for sport harvest. The National Marine Fisheries Service operates a research hatchery on south Baranof Island at Little Port Walter, and the Metlakata Indian Community operates Tamgas Hatchery on Annette Island (see map below).

How many fish and what species can a hatchery produce?

Alaska PNP hatcheries do not grow fish to adulthood, but incubate fertilized eggs and release resulting juveniles back into the wild. By protecting eggs from predators and environmental factors, survival from egg to fry is about eight times higher in hatcheries than in the natural environment. As a result, compared to wild stock production, a much higher percentage of the hatchery return can be harvested while still providing broodstock to continue operations.

How many fish and what species can a hatchery produce? That depends on the amount of freshwater available and the species grown. Alaska PNP hatcheries draw their water from a lake or stream through a permit from the state. Freshwater is needed for both incubating eggs and rearing juvenile salmon. So, the more salmon you have in rearing tanks requiring fresh water, the fewer eggs you can have in incubation. Soon after hatching, pink and chum salmon fry can be transferred directly from fresh water incubators to salt water net pens, where they acclimate and are fed for a few months and released. King, sockeye, and coho salmon, on the other hand, must spend a year or more rearing in fresh water before developing to the smolt stage, when they can tolerate salt water. Pink salmon will return two years after eggs are collected. Other species have longer production cycles. Thus, it comes down to water, expense, and value of the return. These are the economic factors that PNP Hatchery Board of Directors and their constituents weigh in operating their hatcheries. Although king, sockeye, and coho salmon garner higher prices per pound at harvest, chum and pink salmon cost less to rear and generally provide a higher economic return on production costs, requiring less "cost recovery" harvest to pay for hatchery operations and leaving more fish for the commercial and sport fisheries to harvest.

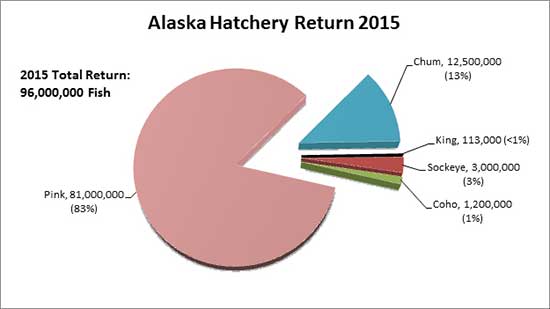

As a result, most of Alaska’s PNP hatchery production is pink and chum salmon (Figure 3). Sockeye, coho and king salmon are also produced, but usually in concert with, and subsidized by, chum or pink salmon production. Local, state and federal government also fund some PNP hatcheries to raise king, sockeye, and coho salmon for commercial and sport fisheries.

How are salmon fisheries managed for hatchery returns to ensure wild stocks are protected?

Alaska’s salmon populations are managed to ensure adequate numbers of adults spawn in the wild, which is called the “spawning escapement”, or “escapement” for short. Salmon stocks are arguably managed at their maximum harvest level each year, given fluctuations due to environmental variability and imperfect management precision. Hatchery production provides a means to increase the overall harvest by supplementing – not replacing - the catch of naturally produced salmon.

The success of Alaska’s hatchery program is attributable to development of state practices over the years to ensure hatchery returns do not negatively impact wild stocks. Alaska's hatcheries use stocks taken from close proximity to the hatchery so that any straying of hatchery returns will have similar genetic makeup as the stocks from nearby streams. Alaska hatcheries do not selectively breed for a particular characteristic. Broodstock is selected without regard to size or other characteristic to maintain genetic diversity. Most Alaska hatchery release sites are located away from important natural salmon stocks so that fishery managers can determine the strength of wild stocks in the catch and manage wild stocks conservatively. The salmon stocks used in the hatcheries, the locations of hatcheries and release sites, and the number of juvenile salmon released are regulated by ADF&G through an extensive permitting process that includes public participation and a thorough vetting of hatchery operations for fish health, impacts to fisheries management, and potential genetic interaction with naturally spawning stocks.

Marking and tagging salmon

Alaska’s PNP hatchery program has a history of active assessment and innovation. Hatcheries use either coded-wire-tag or otolith marking (or both) to mark releases. During the fishing season, the catch is sampled to measure the magnitude of wild and hatchery stock returns, allowing fisheries managers to manage for wild stock escapement goals. Hatchery release sites are located such that, if fishery managers need to restrict fishing in the traditional wild stock fishing areas for conservation, the hatchery fish will pass through those areas to the hatchery release sites that are usually located in isolated bays where few wild stocks are present. At these release sites, hatchery stocks can be fully harvested with minimal impact to wild stocks.

Coded wire tagging is done by inserting a tiny piece of wire engraved with a code into the snouts of juvenile salmon. After the tag is inserted, the adipose fin of the fish is clipped. When the fish return as adults, the catch can be examined for fish missing their adipose fin, and the tags removed from these fish to determine their origin. Coded wire tagging is laborious and expensive. Only a fraction of a release is tagged. When the released fish return as adults, the hatchery contribution to the catch is estimated by multiplying the number of tags recovered by an expansion factor based on the fraction of the juvenile release that was tagged. Therefore, if only a very small fraction of the release can be tagged, as was the case in the early years of the hatchery program for large releases of pink and chum salmon, the estimate of the hatchery contribution to the catch contained a lot of uncertainty.

Otolith marking, which was first implemented on a production scale in Alaska, changed all that. Thermal otolith marking is done by alternating warmer and colder incubation water over about a three to six day period, usually during the egg stage. This procedure will lay down alternately dark and light rings on the fish’s ear bone (called the otolith), similar to rings on a tree. Naturally spawned salmon will have less distinct marks that lack regularly spaced intervals. Fish can be marked with different patterns of thermal marks, allowing for stock separation among hatcheries or even release locations.

The development of otolith marking is a powerful tool. During the adult harvest, a sample of otoliths will be taken and read to estimate how many hatchery origin fish are in the catch, and which hatcheries the fish were released from. Because all fish in a hatchery can be marked this way – and not just a fraction of the releases as normally occurs when hatchery releases are coded-wire-tagged – a much more accurate assessment can be made. In addition, otoliths from immature salmon caught on the high seas can be used to determine origin and migration pattern, and otoliths from spawning carcasses can be collected during stream surveys to assess straying.

Today most of Alaska’s PNP hatcheries otolith mark pink and chum salmon releases, and work cooperatively with ADF&G to assess the hatchery contribution to the catch during the season to provide ADF&G managers the information they need to manage for wild stock returns. Much of the king, coho and sockeye salmon releases are otolith marked as well.

Coded wire tagging remains in use for coho and king salmon. Because these species are released in lesser numbers, a higher fraction of the release can be tagged and provide an acceptably precise estimate of contribution to the catch. In addition, ADF&G conducts wild stock assessments for coho and king salmon by capturing, coded-wire tagging, and releasing wild smolts in streams in some areas of the state. Coded-wire tag data provides an essential tool to accurately monitor both the hatchery component of the harvest and the wild stock dynamics for these two species.

Sustainable Returns

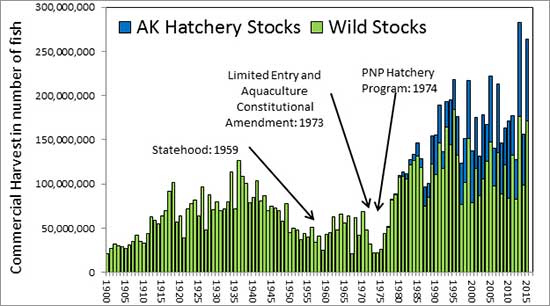

A combination of favorable environmental conditions, restricted fishing effort, abundance-based harvest management, habitat improvement, and hatchery production gradually boosted salmon catches from the dismal returns in the early 1970’s. Today, Alaska’s salmon fisheries are among the healthiest in the world, with the two highest overall harvests in the past three seasons. The 2013 salmon season was a record harvest overall, with the 283 million fish commercial harvest comprised of the second highest catch for wild stocks (176 million fish) and the highest catch for hatchery stocks (107 million fish). The 2015 salmon season was the second highest harvest overall, with a 264 million fish commercial harvest comprised of the third highest catch for wild stocks (170 million fish) and the second highest catch for hatchery stocks (93 million fish). The hatchery harvests alone in both 2013 and 2015 were greater than the entire statewide commercial salmon harvest in every year prior to statehood except for 7 years (1918, 1926, 1934, 1936, 1937, 1938 and 1941).

In addition, there are no salmon “stocks of concern”, i.e., salmon stocks that do not regularly meet escapement goals, in Prince William Sound or Southeast Alaska, where most hatchery production occurs. This indicates that adequate escapements to wild stock systems are being met in these areas over time. Therefore, although hatchery production may comprise a majority of the harvest of a species in a region – chum salmon in Southeast Alaska or pink salmon in Prince William Sound, for example – this does not mean that it is at the expense of wild stock production. In fact, when fishing is open elsewhere to target wild stocks, the fleet may instead focus effort on hatchery returns at hatchery release sites, particularly when tender service (vessels that carry a fishing boat’s catch to a processor) is also concentrated there. Commercial fishermen can efficiently harvest hatchery fish and offload to nearby tenders, saving time and fuel in their operations. As intended, hatchery production is supplementing the healthy wild stock returns, and is a reflection of the state’s priority of conservation of wild stocks as the foundation of its salmon enhancement and management programs.

The Salmon Marketplace

The salmon marketplace has changed substantially since Alaska’s PNP hatchery program began. As the first adult salmon were returning to newly built hatcheries in 1980, Alaska accounted for nearly half of the world salmon supply, and larger harvests in Alaska generally meant that the prices paid to fishermen by the processor – called the exvessel price - was lower in larger harvest years. By 1996, rapidly expanding worldwide farmed salmon production surpassed the wild salmon harvest for the first time, and wild salmon prices declined precipitously as farmed salmon flooded the marketplace in the U.S., Europe, and Japan.

By the early 2000s, many Alaska hatchery organizations and commercial fishermen struggled to remain financially solvent during these years of low salmon prices. Several hatcheries suspended operations altogether. Processors placed fishermen on delivery limits because of limited capacity and a glutted market.

Alaska responded to farmed salmon competition by improving fish quality and implementing marketing efforts to define the differences between Alaska salmon and farmed salmon. By 2004, these efforts began to pay off through increasing demand and prices.

Part of Alaska’s marketing efforts was a message of sustainable fisheries management to a growing audience of discriminating buyers. In 2000, salmon fisheries managed by the State of Alaska were the first salmon fisheries certified as “sustainably managed” by the independent nonprofit Marine Stewardship Council (MSC) and remained the only MSC certified salmon fisheries in the world for nearly a decade. Alaska’s certification was MSC’s broadest and most complex, covering all five salmon species harvested by all fishing gear types in all parts of the state. Achievement of statewide certification was a reflection of the state’s commitment to abundance-based fisheries management and constitutional mandate to sustain wild salmon populations.

Strengthening trade ties with China also contributed to higher salmon prices. An increasing portion of Alaska’s harvest was headed, gutted, and frozen in Alaska, shipped to China for further processing to fillets and other product forms, and then shipped back to the US or other markets for sale or further value-added processing. According to the Alaska Seafood Marketing Institute May 2011 Marketing Bulletin, by 2010, roughly a third of all Alaska seafood was exported to China to be re-processed and re-exported to markets in the U.S. and Europe.

Today, Alaska typically accounts for just 12% to 15% of the global supply of salmon. Alaska’s diminished influence on world salmon production means that Alaska’s harvest volume has little effect on world salmon prices. For example, the price per pound for pink salmon trended upward in the first eight years of the past decade, despite large fluctuations in harvest volume, before declining from 2013 to 2015.

In recent years, the strong dollar, political action in Russia, and the record pink salmon harvest in 2013 harvest were key factors influencing price declines of pink and chum salmon, the two primary hatchery-produced species, according to the Alaska Seafood Marketing Institute Spring 2015 Alaska Seafood Market Bulletin. Russia, Japan and Ukraine are key markets for Alaska salmon roe, an important product impacting the overall value of pink and chum salmon. The Russian embargo on US Seafood Products, and lower currency values in Russia, Ukraine and Japan, influenced the pink salmon market, as did the large inventory of canned salmon from the 2013 harvest. Chum salmon value was similarly affected by the lower yen value in Japan. Japan is a major buyer of chum salmon roe. Since most fish farms do not rear salmon to maturity, wild salmon continue to dominate this part of the market. Roe typically accounts for about half of the wholesale revenue of chum salmon, and pink and chum salmon together provide the majority of salmon roe produced in Alaska.

Alaska PNP hatchery production is harvested primarily in the common property commercial fisheries, followed by the cost recovery harvest, which pay for hatchery operations. The sport, personal use and subsistence harvest are a small portion of the overall PNP hatchery harvest, but particularly important to harvesters in accessible locales such as Ketchikan, Juneau, Sitka, Valdez, Kodiak, Resurrection Bay, the Copper River, and lower Cook Inlet.

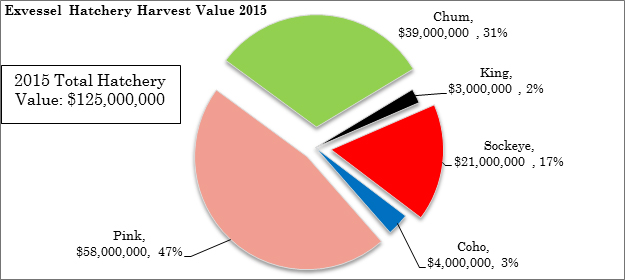

About 93 million hatchery salmon were harvested in the commercial fisheries in 2015, worth an estimated exvessel value of $125 million. Pink salmon comprised 47% of the total value, followed by chum salmon (31%), and sockeye salmon (17%).

By region, Prince William Sound and Southeast Alaska PNP hatcheries produced most of the hatchery production in 2015, followed by Kodiak and Cook Inlet areas.

The Fairbanks and Anchorage ADF&G sport fish hatcheries, paid for and operated using funds from the sale of sport fish licenses and federal excise taxes collected from the sale of sport fishing equipment, provide the Interior and Southcentral regions with sport fishery enhancement, stocking numerous freshwater lakes with Arctic char, rainbow trout, coho and king salmon, as well as several marine terminal fisheries with coho and king salmon. You can find out more about sport fish hatcheries and stocking at the ADF&G website.

Prince William Sound hatcheries produce the majority of hatchery pink salmon in the state. The Prince William Sound purse seine fishery, which harvests primarily pink salmon, was closed during the poor salmon returns years of 1972 and 1974, with minimal fishing in 1973. Fishermen and processors were anxious to get hatchery production on line quickly to aid in the recovery of the fishery, and pink salmon were both a targeted species and provided the quickest turnaround from egg take to harvest. Pink salmon were, and continue to be, the most abundant species in Prince William Sound, with an historic infrastructure in place for processing pink salmon. The Kitoi Bay Hatchery on Afognak Island near Kodiak is another substantial producer of pink salmon in the state.

Southeast Alaska hatcheries produce the majority of hatchery chum salmon in the state. Wild chum salmon runs return during the same period as sockeye and pink salmon runs, and chum salmon are the least abundant of these three species. ADF&G manages the salmon fisheries primarily to meet escapement goals for sockeye or pink salmon, with chum salmon caught incidentally. During the development of the hatchery program in Southeast Alaska in the early 1980’s, fishermen, processors and ADF&G assessed that chum salmon could be produced in hatcheries and that returns would be caught incidentally in the fisheries managed for wild pink or sockeye salmon. Hatchery release sites were selected so that chum salmon not caught in the sockeye and pink salmon fisheries could be caught at the release sites without a significant harvest of wild stocks.

Prince William Sound hatcheries produce the majority of hatchery sockeye salmon. The largest returns are to Main Bay Hatchery, where a sockeye salmon smolt program was developed to enhance the sockeye salmon drift and set gillnet fisheries on the west side of Prince William Sound to balance the pink salmon hatchery production that primarily benefits the seine fleet. Sockeye salmon are also produced from streamside incubators along the Gulkana River, a tributary of the Copper River, and these fish are caught primarily during the Copper River commercial drift gillnet, personal use dipnet, and subsistence fish wheel harvests. The Gulkana program was established in the early 1970’s as a mitigation measure from habitat loss during construction of the Richardson Highway.

Southeast Alaska hatcheries produce the majority of hatchery coho salmon. Southeast Alaska has the largest coho salmon commercial fishery in the state, accounting for about half of the statewide coho salmon harvest in 2015. Returning coho salmon are available to commercial hook-and-line salmon trollers in Southeast Alaska, the only region where commercial trolling occurs, from July through September. This is unlike other regions of the state, where coho salmon are commercially fished with net gear and targeted only during a few weeks during the fall return. Coho salmon are produced by hatcheries in Cook Inlet and Prince William Sound, as well, that are particularly important to the sport fisheries in Resurrection Bay and Prince William Sound.

Most king salmon hatchery production occurs in Southeast Alaska, where most of the state’s king salmon harvest takes place. King salmon hatchery production was largely developed after the Pacific Salmon Treaty (1985), which included funding for king salmon hatchery production in Southeast Alaska to mitigate harvest concessions made in the treaty. King salmon are targeted year round by the commercial troll fleet, and are important seasonally to the sport and net fleets.

PNP hatchery operations and employment make a substantial economic impact in Alaska as well. In 2014, the operation budgets for all PNP hatcheries in the state totaled about $50 million. By comparison, the statewide operating budget for ADF&G Division of Commercial Fisheries in 2014 for management of all state fisheries was about $70 million.

Hatcheries are not without controversy. Studies of hatchery effects on wild stocks and fisheries management in Lower 48 systems, where hatcheries operate largely to replace – not supplement – fisheries, regularly raise a healthy concern over Alaska’s hatchery program, despite the state’s long track record of sustaining wild stocks and providing additional harvest of hatchery returns. ADF&G has monitored straying of hatchery fish into wild systems in all areas of the state where salmon are released. Recently, a science panel composed of scientists with broad experience in salmon fishery enhancement, management, and wild and hatchery interactions from ADF&G, University of Alaska, aquaculture associations, and National Marine Fisheries Service was assembled to design a long-term research project to further study some of the questions of hatchery and wild stock interactions in Alaska. The study, entitled “Interactions of Wild and Hatchery Pink and Chum Salmon in Prince William Sound and Southeast Alaska”, is currently underway. The proposed study length is about eleven years, with four years initially funded. Study funding is provided by the PNP operators, salmon processors, and state of Alaska, and administered by ADF&G. Field work is conducted by the Prince William Sound Science Center and the Sitka Sound Science Center. The study will improve understanding of hatchery and wild stock interactions and provide Alaska-specific scientific guidance for assessing Alaska’s hatchery program.

Subscribe to be notified about new issues

Receive a monthly notice about new issues and articles.