Alaska Fish & Wildlife News

April 2016

White-nose Syndrome in Bat

Shocks Researchers with Arrival in Washington

Since it was first detected on the east coast of the United States nearly a decade ago, a devastating disease — White-nose Syndrome — has been ravaging little brown bats as they hibernate in huge groups, killing tens of thousands in a single winter. In March, the disease was detected for the first time in one little brown bat on the West Coast.

For researchers in Alaska and beyond, this is not good news.

According to a news release from the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife in late March, a hiker in Washington State found the bat unable to fly near a forested trail on March 11 near North Bend, a community 30 miles east of Seattle. At the time, the sick bat was collected for rehabilitation and taken to the Progressive Animal Welfare Society for care. The bat died two days later and had visible symptoms of a skin infection — the same type of symptoms associated with WNS. A test later confirmed the bat had indeed died as a result of the fungus.

This development doesn’t sit well with bat researchers like Karen Blejwas, a wildlife biologist with the Alaska Department of Fish and Game. Since 2011, Blejwas has studied the six species of bats that live in Southeast Alaska, including the most prevalent — Myotis lucifugus, the scientific name for the little brown bat.

“Nobody expected this to happen,” she said. “This just means to me that it can show up anywhere.”

WNS has spread quickly among bats in other affected areas, and the death toll has reached more than six million since it was first documented. That’s a big blow to a species that plays an important, insect-eating ecological role.

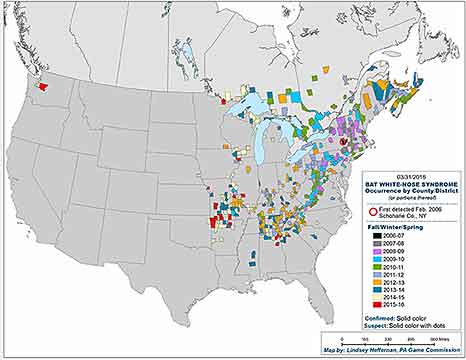

First seen in North America in the winter of 2006/2007 in eastern New York, WNS has now spread to 28 states and five Canadian provinces. David Blehert, a microbiologist with the U.S. Geological Survey, first identified the known fungus, Pseudogymnoascus destructans, which causes the disease. WNS is named for the fuzzy white fungal growth that is sometimes observed on the muzzles of infected bats. The fungus invades hibernating bats’ skin and causes damage, especially to delicate wing tissue, and causes physiologic imbalances that can lead to disturbed hibernation, which in turn causes an increase in the use of fat reserves, dehydration and eventually death.

Scientists believe the fungus originated in Europe, but there’s no mortality associated with bats in Europe who contract WNS. And, the fungus has also been detected on other bat species, like big-eared bats for example, Blejwas said. But those bats don’t ever develop the disease.

“There’s a longer list of (bat) species who have had the fungus detected on them, than have actually developed white-nose,” she said.

Moreover, scientists believe there might be multiple strains of the fungus, but currently the genetic testing of the spores is still underway. Researchers hope this information might lead to clues as to why North American little brown bats are more susceptible to the disease. They are also considering environmental factors, such as humidity, Blejwas said.

As scientists dig deeper into the make-up of the WNS-causing fungus, one looming question still remains: How did the fungus make a 1,300-mile jump across a major geographic barrier like the Rocky Mountain Range? Or did it …

Blejwas finds that possibility unimaginable.

“It’s perplexing,” she said. “Bats of this type don’t range that far.”

“We have no evidence in the West that they are moving that far, but there have been long distance movements recorded back East, up to something close to 600 kilometers, but that still wouldn’t put a bat from the East into the West.”

Little brown bats that spend the summer in Juneau’s Mendenhall Valley, or Fish Creek, for instance, are the same bats that will hibernate in Fish Creek or the valley, Blejwas said.

“In the fall, they will do these kind of wandering movements that are probably related to mating. And I don’t know how far they go then,” she said. “But the genetics suggest that the (little brown bat) populations are more geographically restricted in the West than they are in the East.”

This is because of the way they hibernate. In the eastern part of the U.S., little brown bats congregate in huge hibernaculums — often in caves or mines which are aplenty — and numbers of bats spending the winter together can number around 100,000. In Southeast Alaska however, bats hibernate in areas that stand out in stark contrast. Blejwas said they can be found singly or in very small groups — certainly less than a dozen — roosted up in root wads, moss-covered boulder clusters, or simple holes in the ground that can wind meters below the surface.

That means that should WNS ever make its way north from Washington, the chances of it spreading as rapidly as it has in eastern U.S. states is unlikely. Still, the arrival of the disease on the West coast is of grave concern for researchers like Blejwas.

“Before this happened, I would have thought we would have years, maybe even more than a decade …” she said.

Perhaps one of the most perplexing facts in this unsolved mystery is this: The bat infected with WNS in Washington was not an eastern bat; instead, it was a sick western bat. In other words, it’s not an eastern bat with an eastern disease, it was a western bat with an eastern disease.

“Up until now, evidence has strongly suggested that WNS moves through bat-to-bat transmission,” Blejwas said. “It just makes no sense when considering what we know about white-nose up until this point. That it would show up in a western bat, over that long of a distance, there’s no way that little browns from the east are flying that far.”

Blejwas said she hopes the genetics of the fungus will hopefully tell people whether or not the disease came from the East, or if it was a possible introduction from Asia. She said the latter scenario is entirely possible considering how many shipping containers arrive in large port cities like Los Angeles and Seattle.

One bat researcher in British Columbia might have a lead on how the Washington bat became sick. Cori Lausen, who has a Ph.D in the landscape genetics and roosting ecology of bats, told Blejwas a story of, “A flock of bats that escaped from the hold of a Chinese cargo ship in Vancouver, BC, back in November 2012.” As the story goes, the crew of the ship noticed a group of bats flying around the cargo hold. One was captured, and sent for testing. That bat was not tested for the fungus that causes WNS and was later destroyed. Unfortunately, the cargo hold door was left open and the rest of the bats were never recovered.

“This incident suggests that the most likely source of WNS in Washington arrived from Asia via the port of Seattle,” Blejwas wrote in an email. “It will be at least a couple of months before they can genotype the fungus on the Washington bat and determine if it is a European, North American, or Asian strain (and yes, there is a difference), but in my mind this is the only explanation that makes any sense for WNS showing up in western Washington.”

As data is analyzed, there’s still plenty researchers and the general public can do to ensure this deadly bat disease is monitored closely.

“We don’t have any caves or mines that we can go to where we know that we have hibernating bats,” Blejwas said. “And so the disease was detected because there was a bat found on the landscape and turned in by a member of the public and was sent for testing, luckily.”

She said that’s probably our best means of detecting it relatively early in the West — by a member of the public chancing upon a sick or dead bat and turning it in for testing.

Now, in the spring, is when little brown bats are emerging from hibernating and now is when it’s most important to be on the lookout for infected bats. Blejwas said this is because any infected bats will clear the fungus shortly after they become active again. In no time, it will be too late to detect the fungus. This year, the bats came out earlier than normal in Southeast Alaska — in early March instead of early April, Blejwas said.

“The fungus only grows on hibernating bats,” she said. “If the disease does not kill an infected bat over the winter, they will clear the fungus and repair their tissues.”

Despite the devastating effects of this disease, Blejwas said there are some bats surviving back East in small numbers. Today, researchers are starting to look at why, and what characteristics the surviving bats carry.

If you find a sick or dead bat

Should someone in Alaska find a dead or sick bat, the first rule is never touch it with bare hands, Blejwas said. Use gloves or if you don’t have any, turn a baggie inside out to pick up the bat. If the bat is dead, double bag it. If the bat doesn’t smell or isn’t in a moderate state of decay, don’t freeze it. Just keep it cool. The individual should then immediately contact the Alaska Department of Fish & Game, either Blejwas in Southeast or Marian Snively, for the rest of the state.

“If they can’t get a hold of one of us,” Blejwas said, “they should contact their local Fish & Game office. Basically, the bat would then be sent off to a vet for additional testing and screening.”

And a sick bat isn’t hard to recognize. If you find it during the day out in the open, it’s probably an unwell bat, Blejwas said, because bats will roost during the day in a tree, or crack, or house or in a secure location. And, chances are, she said, you’re not going to find it. They will occasionally fly during the day, but that’s not a sign that something is wrong.

For more information on how to handle a sick or dead bat

To contact Karen Blejwas: karen.blejwas@alaska.gov

To contact Marian Snively: marian.snively@alaska.gov

For more information on White-nose Syndrome

Alaska's Bat Monitoring Program

Little Brown Bat species profile

For more on bat research in Alaska

Alaska's Bat Monitors - How to be a Citizen Scientist

Bat video:

Bat Captures in Southeast Alaska

Abby Lowell is a contributing writer to Alaska Fish and Wildlife News and serves as an education specialist with the Alaska Department of Fish and Game’s Division of Wildlife Conservation. She is based in Juneau.

Subscribe to be notified about new issues

Receive a monthly notice about new issues and articles.