Alaska Fish & Wildlife News

May 2015

Alaska’s Five Species of Pacific Salmon

Lifecycle and Identification

There’s an easy way to remember the names of each of Alaska’s five different species of Pacific salmon. It’s a method we often use when educating young kids about the different species and the salmon lifecycle. And it works.

We ask kids to hold one hand up and spread their fingers. We motion to the thumb and say, “Thumb rhymes with chum.” Then we ask them to use their pointer finger and point to their eye. “Point to your eye. Eye rhymes with sockeye.” The middle finger is the largest finger on the hand and, while there’s no catchy rhyme to remember, we say the largest of all of Alaska’s salmon is the king. Then we look at the ring finger and ask, “What color rings to some people wear?” Gold? No. What’s another color? Silver. Yes. The fourth species is a silver. And last but not least, there’s the pinky finger. Easy enough to remember that the fifth species of Alaska’s Pacific salmon is the pink.

Being able to name the five different species and knowing how to correctly identify all five is a little bit more complicated. And understanding how to tell an adult pink from a chum or a king from a coho begins with the salmon lifecycle.

And yes, there will be a quiz at the end of this.

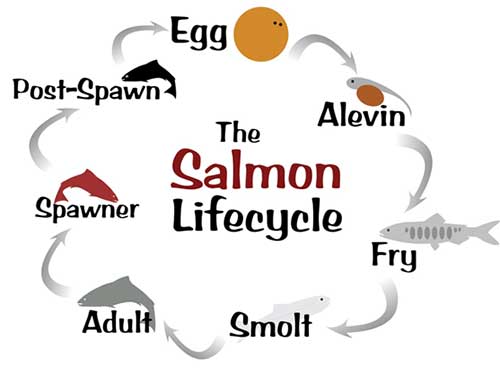

A brief overview of the lifecycle of Pacific salmon

All of Alaska’s salmon begin their life as a fertilized egg in freshwater. Depending on the species and water temperature, the eggs incubate for a given length of time in the safety of the gravel in a river or lake. As the salmon develops within the egg, it undergoes certain physical changes like the development of eyes, a spine and a tail. Eventually, the egg will hatch, leading to the next life stage called the alevin. Alevin are small and can be identified by the large orange yolk sac attached to the body. Alevin remain in the gravel, protected from predators and receive nutrients from the yolk sac. At this stage, small tails are present. As the alevin grows, the nutrients in the yolk sac are depleted and the salmon begins to develop mouth parts, as well as small, ovular shapes along each side of its body. This is the point when the fish begins to leave the shelter of the gravel bed and swim around in search of food. This stage is called the fry stage.

Most, but not all, salmon fry have parr marks along each side of their body. Pink salmon fry do not have parr marks. Parr marks act as camouflage, protecting the juvenile salmon from predation. While fry are strong swimmers, they will seek out refuge in slower-moving water where they are protected from predators and where they can find food such as insect larvae and plankton.

Each species of salmon fry will remain in freshwater for a determined length of time. Some, like sockeye and silver salmon, will stay in freshwater for a year or two. Others, like pink and chum salmon migrate to sea soon after emergence. King (or Chinook) fry typically remain in freshwater for approximately a year.

As the salmon fry prepare to migrate to sea, they lose their parr marks and enter the next stage of their life, which is the smolt stage. Smolt vary in size by species and normally rear in brackish water where the sea meets freshwater. Smolt grow rapidly and when the salmon reaches a certain size, it will begin its open-ocean migration, and thus enter the adult stage of its life.

Adult salmon will remain in the ocean feeding for a given length of time depending on the species. Kings can stay in saltwater for up to 6 years, while pink salmon are on a two-year cycle, meaning they return to spawn in freshwater as two-year-old fish.

Upon returning to freshwater from the sea, salmon undergo significant physical changes. Some, like sockeye, kings and silvers develop a deep maroon or red coloration. In Southeast Alaska, spawning king salmon are more of a dark brown or blackish color. Chum salmon develop calico bands along each side of their body. Males of each species develop large, hooked jaws, called “kypes.” In addition to developing a kype, male pink and sockeye salmon develop pronounced humps on their back. Consequently, pink salmon are often referred to as “humpys.”

Salmon returning to freshwater to spawn are called “spawners,” which is the next stage of their life. Pacific salmon spawn in the stream or lake they were born in; some spawn in almost the same location where they emerged from their egg. Each species enters freshwater at different times of the year. In many river systems, kings are the first species to return, followed by sockeye, pinks, chums and lastly silvers. Like most naturally occurring events in nature, Pacific salmon run timing isn’t always consistent year-to-year, and pinpointing the day or week of any given month when a particular species of salmon will appear in freshwater is speculative at best.

In their natal stream, salmon begin the migration upriver to reach their spawning ground. The length a salmon will travel to reach the spawning grounds varies by river and by species. There are chum salmon in the Yukon River in Alaska that migrate well over 2,000 miles to reach their spawning grounds.

Once the salmon has reached its spawning grounds, the female and male pair up. The female digs a bed in the gravel called a “redd.” This is where she will deposit her eggs as the male fertilizes them with his milt. After spawning, all species of Pacific salmon die, completing their lifecycle.

Identifying the five species of Pacific salmon native to freshwaters of Alaska

There are a few physical characteristics that remain consistent in adult and spawning salmon that can be used to more accurately identify the species. Whether you are an avid sport fish angler and plan to target salmon on rod and reel, or if you’re an Alaskan who takes to the river with a dip net in hand, these techniques may help in positive salmon identification.

It should be stated that these are common identification techniques meant to help educate anglers. Any angler who is not completely sure of the species of salmon they have caught should release the fish back into the water unharmed.

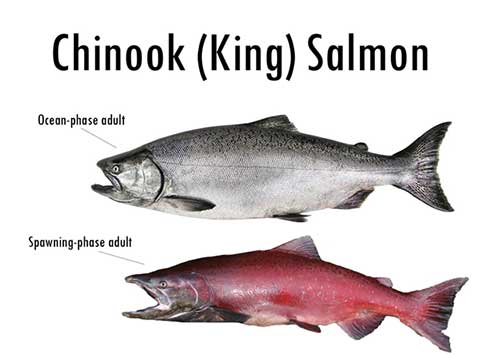

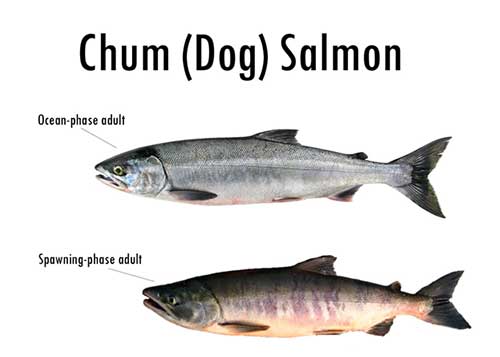

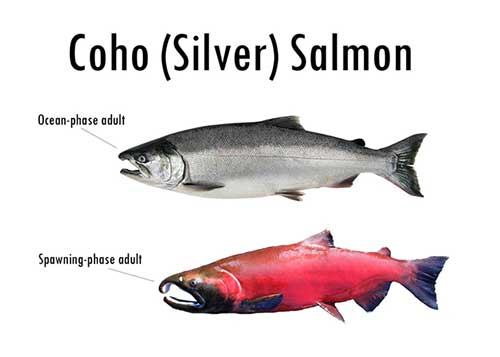

Pacific salmon in their marine or ocean phase can look very much alike. They are normally a bright silver color with almost no spawning coloration. Even adult salmon returning to spawn in freshwater will often have the bright silvery appearance, depending on how long they’ve been in freshwater. It’s usually after the salmon has been in freshwater for an extended period of time that they develop the strong physical characteristics of spawning salmon.

There are a few physical characteristics that do not change as the adult salmon begins its spawning migration. First, adult Pacific salmon that have spots on their back or tail do not lose them. Two species of Pacific salmon do not have spots on their back or tail at all. These are the chum and the sockeye. In very rare cases, and in very isolated locations, there have been a few sockeye and chum salmon identified with small spots on their back or tail.

Ocean-phase and spawning-phase salmon

Chum Salmon

An adult spawning chum displays the tell-tale calico bands along each side of its body. These bands are often deep purple, green, and dull yellow. Both male and female spawning chum salmon develop these bands. Spawning and ocean phase chums have a white mouth with a white gum-line. An ocean-bright chum can be difficult to differentiate from an ocean-bright sockeye. But unlike sockeye, chum salmon have a white tip on the anal fin, deeply forked tail and a large pupil.

Sockeye salmon

Male and female spawning sockeye develop a deep red coloration on their body. Their head turns a greenish color, while their tail remains devoid of significant coloration. The male develops pronounced shoulders and a large kype. Spawning and ocean-phase sockeye have a white mouth with a white gum-line.

Coho Salmon

Spawning coho (or silver) salmon develop a deep reddish or maroon coloration that covers their entire body – head and tail included. Ocean adults and spawning-phase coho have small black spots that run along the back and on the upper lobe of the tail. Coho also have a dark gray or blackish mouth with a white gum-line.

Chinook salmon

Ocean-phase and spawning chinook (king) salmon have a black mouth with a black gum-line. They have black spots on their back and on both lobes of the tail. Kings are different from coho in that their tail spots cover both lobes, whereas a coho has spots only on the upper lobe of its tail.

Pink Salmon

Pink salmon – ocean phase adults and spawners – are the smallest of all five species. Pinks have large, ovular spots on their backs and on both lobes of the tail. Spawning males have a very pronounced hump on their back. Their mouth is white with a black gum-line.

With a little experience looking closely at the mouth and tail of a Pacific salmon, you should begin to become more confident in your Pacific salmon identification skills. Ultimately, it’s an individual angler’s responsibility to know what species of fish they retain. And as stated before, if you are unsure of the species you caught, release the fish back to the water unharmed.

Now test your Pacific salmon identification and lifecycle knowledge by taking our online quiz.

And be sure to participate in the Five Salmon Family Challenge. More information on that can be found here: http://www.adfg.alaska.gov/index.cfm?adfg=fishingSport.fiveSalmonFamily .

Subscribe to be notified about new issues

Receive a monthly notice about new issues and articles.