Alaska Fish & Wildlife News

November 2014

Kenai Moose and the Funny River Fire

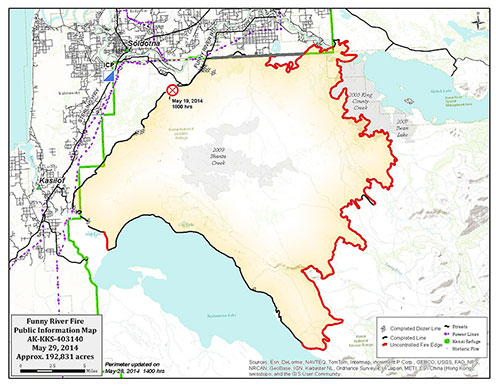

The Funny River Fire - Alaska’s biggest fire of the year - burned a huge swath of the Kenai Peninsula in the spring of 2014. Fish and Game is investigating how the fire may benefit moose in the area.

The Funny River Fire

More than 500 people were engaged in fighting the fire during the last weeks in May, as it burned through the Kenai National Wildlife Refuge and threatened the communities of Kasilof, Funny River and Sterling. Conditions were ideal for the fire. By the time the human-caused fire was reduced to smoking ash, the burn encompassed an area of almost 200,000 acres. Sue Rodman explains how and why the fire was so extensive.

“Most of the stands of black spruce in there were over 60 years old and they were prime for burning,” she said. “They’re 30 feet tall or more, they have limbs that go all the way to the ground, and the understory vegetation is cranberry and blueberry that burns really well.”

Rodman has a forestry background and works on landscape and fire-related projects for Fish and Game, sometimes using fire as a tool to enhance habitat in areas like the Alphabet Hills near Delta Junction. She said spruce are particularly flammable trees.

“Spruce trees have less moisture in them when they’re alive than most trees do when they’re dead,” she said. “You combine that low moisture content with the amount of volatile contents in the sap and needles, and they burn great.”

Many trees are mostly water. The materials that make up the wood and bark weigh less than the water inside the tree. Rodman said the moisture-to-weight volume is 200-300 percent in most live trees, a cottonwood, for example, is 300 percent, most of the tree’s weight is water. In spruce the ratio is about 60 percent.

The flammable spruce combined with three other factors: low humidity (20 percent), a dry wind from the north, and an abundance of dry grass. Rodman said in the wake of the Kenai Peninsula’s spruce bark beetle epidemic in the mid-1990s, there are a lot of dead spruce trees and Calamagrostis grass, a tall, reedy grass that can burn well under the right conditions.

“Grass is what’s called a ‘fine fuel,’” she said. “These fuel types give up and receive moisture very quickly, like within an hour, so when humidity drops from normal of 40 to 50 percent to 20 percent, they give up a lot of moisture.”

The fire ignited in the afternoon of May 19 on the south side of Funny River Road. Initially driven south by the winds, it burned all the way to the north shore of Tustemena Lake. Following the initial run, it burned east toward the Kenai Mountains and north, where it briefly jumped across the Kenai River.

“It was a human caused fire started in the grass, and it ran,” she said.

Not a Moonscape

“You hear 200,000-plus acres burned and you picture a moonscape – it’s not like that,” said wildlife biologist John Crouse. Crouse lives in Sterling, near the burn, and studies moose on the Kenai Peninsula. “The ground was still frozen in a lot of areas, and in some areas it just scorched the tops of trees. By July there was already green coming back.”

The area is not all spruce forest – there are wetlands, and stands of cottonwood, aspen and birch. Those trees have much higher moisture content than spruce, and the landscape itself in some areas is wetter.

“Because relative humidity is sensitive to depressions in the landscape, a lot of riverine or stream areas didn’t burn,” Rodman said. “So that’s part of why we ended up with a mosaic. The 2009 Shanta creek fire was in the middle of the Funny River Fire (area), and that modified the fire behavior. It created fire breaks; there were chunks of habitat that had already burned there.” (See map above)

Rodman said foresters are already seeing places where birch, aspen, willow and other hardwoods are regenerating. “There are a lot of places that might not have burned very deep into the duff layer. And where it did, bare soil is receptive to reseeding. It looks like there is going to be a nice mosaic of regenerating forage for moose. Moose love fireweed,” she said.

Moose and the Kenai Peninsula

The landscape at the northern end of the Kenai (north of the Kenai River) is quite different from the south (south of Tustemena Lake), and now there’s a big burn in the center of the Kenai. Biologists have been comparing moose in different areas of the Kenai, and the burn provides a new opportunity.

Moose researcher John Crouse is the director of the Kenai Moose Research Center near Sterling. He’s working with ADF&G colleagues Thomas McDonough and Dan Thompson to learn more about moose on the Kenai. They are particularly interested in the recruitment of young moose into the population and how the population is growing.

“For the past three years we’ve had 100 moose with VHF collars north and south of the burn,” Crouse said. “We’re tracking them to learn more about their health, birth rates and survival relative to the existing habitat conditions. On the north end of the Kenai big burns in ‘47 and ‘69 really benefitted moose there.”

But the benefits are short term, lasting perhaps a few decades after the fire. Crouse said the moose population has been declining in the north end of the Kenai (Game Management Unit 15a) since the early 1990s. The forest has matured and most of food made available through past fires has grown up and out of reach.

“Forty to sixty years post fire there’s not much difference in food availability to moose between burned and unburned (plant) communities,” Crouse said.

The south end of the Kenai (GMU 15C) is different, and so is the moose population. It’s largely spruce and willow habitat, there’s more variety in elevation and more subalpine landscape, and a different fire history. The moose population has been doing fairly well. Biologists are meeting management and harvest objectives, although there was some concern about bull:cow ratios. Around 2009 bull numbers had dropped to nine bulls per 100 cows, so managers reduced the harvest of young bulls. In recent years they’ve seen younger, breeding-age bulls recruited into the population, and the ratio is up to 20:100.

Wildlife biologist Thomas McDonough is based in Homer, and serves as the principle investigator for the Kenai moose studies. He said comparing moose in the north and the south ends of the Kenai provides insights into habitat quality.

“We have 50 adult cows in each area with VHF collars,” he said. “We capture a subset of them twice a year and assess their condition; in the fall, ostensibly at peak of their condition after summer, then again in March when they’re in relatively poor condition after the winter. Handling animals at both times of the year gives a really good measure of summer and winter habitat quality.”

The work is related to a Board of Game directive to conduct predator control those areas of the Kenai. “These studies are giving some baseline information to help guide those programs,” he said.

Moose in the Funny River Burn

“Now we have a 200,000 acre area impacted by a large burn in the middle of the Kenai,” said Crouse. “With this (upcoming) collaring effort we hope to learn how moose are responding to the disturbance caused by the fire.”

Crouse and his colleagues will be busy in November – they plan to capture 100 moose as part of their studies. GPS collars will be deployed on 25 moose in the burn area and on 25 moose north of the burn. The collars will record the animals’ location every 30 minutes and sensors on the collar will measure motion (acceleration) to allow biologists to determine activity associated with habitat use – was the animal bedded down or active and moving.

A subset of the animals will be equipped with a second monitoring device. Biologists plan to equip 30 moose with internal thermometers that will record and store body temperature every five minutes. Another 10 captive moose at the Kenai Moose Research Center will also be equipped with thermometers for comparison.

“We’ve got areas that are lightly burned, scorched, unburned and severely burned, within the perimeter,” Crouse said. “How are moose using that fire landscape?”

Researcher Dan Thompson will be looking at activity and location relative to the thermal environment, Crouse said. The fire opened up big areas that produce forage. But moose, being large bodied, respond negatively to high temperatures. Areas may not be available to moose if they have to stand out in the sun in warm weather. When moose heat up, at some point they need to stop being active, or dissipate that body heat. They get in lakes, and may go into cooler habitat, such as black spruce forest with cool, moist moss understory, and lay down in the shade.

Thompson hopes to evaluate habitat use based on the thermoregulatory costs to the moose. He’ll have their locations, the environmental temperatures, and the animals’ internal temperatures. Captive animals at the Kenai Moose Research Center, equipped with the same devices, will help biologists interpret what the wild animals are doing.

ADF&G is also looking at improving habitat in the north Kenai, creating fire breaks that will serve as a measure of safety for the public and a swath of regenerating forage that’s good moose food. In the summer of 2015, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service plans to conduct vegetation analysis on the Kenai National Wildlife Refuge, in the burn area, and the Forest service is planning to set up vegetation plots as well, to better understand the regeneration process.

Riley Woodford is the editor of Alaska Fish and Wildlife News

Subscribe to be notified about new issues

Receive a monthly notice about new issues and articles.