Alaska Fish & Wildlife News

March 2014

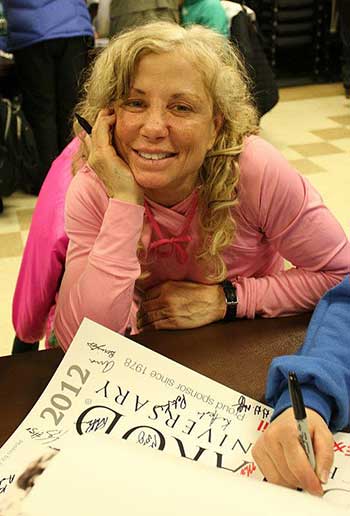

DeeDee Jonrowe

Iditarod Star and Fish and Game Legend

At age 17, she didn’t want to move to Alaska. Now, over forty years later, she’s the sweetheart of the Alaska state sport and an Iditarod favorite.

“I couldn’t think of any fun thing to do," she said. "We’d never really lived in cold weather, and I was bummed out and just wanted to get out of here as soon as I could. And by Christmas, I was so in love with the adventure and freedom of the state of Alaska that I never really ever considered leaving again. I just love this place.”

So began the saga of DeeDee Jonrowe, the world’s foremost female dog musher competing today. But before Jonrowe put in thousands of miles on the Iditarod Trail, she traveled thousands of miles by snowmachine, river boat, and canoe working for the Alaska Department of Fish and Game (ADF&G).

Those were the oil pipeline days, when most workers were flocking to high paying North Slope jobs. Many people tried to discourage Jonrowe from working for Fish and Game. At the time, there weren’t a lot of women working in biologist positions, nor were there female-friendly facilities in the field. Less people were going into resource management, and even less people were taking jobs in western Alaska. Jonrowe took the leap of faith and started out in 1974 as an entry level Fishery Biologist. That leap became the opportunity of a lifetime.

Jonrowe started working for Rae Baxter, where she struck mentorship gold. “Rae was a peculiar man, in a good way. He was determined to see women succeed because he had seen the struggles his wife had in being taken seriously in a male dominated field. So he was determined to not only have a competent woman on the payroll, but he wanted to teach me everything he knew, every wilderness survival trick in the book. I was a willing student.”

Not too long after, her love affair with dog mushing began. Jonrowe gathered a small dog team so she could better attend village meetings in the Bethel area, which were usually accessible by snowmachine. Her genuine respect for the culture she was working with earned her the respect from the locals. “Everybody has their own gift, and I felt like mine was to learn to relate to people, because I really love to work with people. For me, it was all about respecting the resources, being honest, and respecting the people we were working with. Working with the Native people in the Bethel area was just phenomenal. I loved the people out there, and it was while I was in Bethel that I met my husband, who was also working for ADF&G as a fisheries biologist.” She and Mike married in 1977.

Jonrowe balanced her active biologist career with running dogs in the evening and on weekends. Her time spent in Bethel and at ADF&G was remarkable preparation for the thousand-mile race. Jonrowe got her first top ten finish training out of Bethel, and she likely would have not been so well-prepared for a thousand mile race had it not been for her experiences at Fish and Game.

“I loved being a game biologist because I worked with the trappers tagging beavers, and in the summer I would float streams and do beaver cache counts. Commercial fishing management was my very favorite. I flew stream surveys and managed the fishery from inside a boat. Every time there was an opening, I was in the boat, running up and down the district, looking in people’s boats, talking to them, asking how it was going. I spent hundreds of hours on the water. I felt like as a woman, breaking in to this field, I needed to relate to them in a way they could look me in the eye and they knew I knew what I was talking about. That gave me validity. That gave me street cred – river cred – if you will.”

Whether it was with her field crew or her dog team, Jonrowe took the role of player-coach. “I didn’t ask crew members to do anything I wasn’t willing or hadn’t done myself. I worked closely alongside the crew to show I had the expertise to do what it was I was asking them to do.” Jonrowe’s motto was to lead by example and stay positive. “Rae and I built a 250 foot weir across the Holitna River, the first of the major weirs of its kind. We moved over 15,000 pounds of steel and 50 drums of gas, all by ourselves. Many nights I laid in the bottom of my tent with my back aching, but I was determined to not say a word. This was my golden opportunity, and I was so grateful.”

Jonrowe’s tenacity for the outdoors followed her to Mekoryuk, where she lived for one month monitoring walrus and muskox for ADF&G. “Snowmachining from Bethel to Nelson Island to look for herds of muskox was one of the trips I’ll never forget. I ended up with snowblindness and in the hospital for one week. All of that work was good training ground for the Iditarod. Nowadays, they make all the contestants run preliminary races. My preliminary races were at Fish and Game.”

Jonrowe stayed with the department until the fall of 1983 when her thirst for more adventure prompted her to seek other opportunities. “I wanted to spend even more time in the field. Many of us go into fisheries and wildlife management because we love to be outside, gathering the data and doing fieldwork. As biologists get more experienced, we usually get taken out of that environment and stuck in offices to write reports, when in fact that was never what we liked anyway.” After Jonrowe’s tenure with ADF&G, she commercial fished her own boat in Norton Sound, fished for salmon in Bristol Bay, and worked as a sport fishing guide in the Susitna River drainage.

To this day, Jonrowe looks back fondly at her time working for Fish and Game. “A lot of my success on the Iditarod has to do with what I learned from those jobs. I wouldn’t be the person I am today.”

When asked what advice she would give to young Alaskans who want to go into fisheries, Jonrowe said: “Have your education. That’s important. You’ve got to have the basis of recognizing what it is you are observing. Also, students need to realize this is not just resource management, this is ultimately people management. If you don’t have people skills and you don’t want to deal with people, then this truthfully isn’t [for you]. You’re going to be dissatisfied.”

Much of Jonrowe’s advice is appropriate, not just for the classroom, but those in the school of life. “Go in to work realizing you have something to learn from everyone you come in contact with. Realize that no matter who you are approaching today, there is something to learn from that person – maybe something not to do – but something at least. If you hold your tongue and wait a little bit to see where someone is coming from and their background, you can save a lot of conflict.”

Jonrowe continued her advice: “If you’re dissatisfied, sit down and make a list. What is it that’s ultimately at the core of your internal conflict? Then look at it and see how you can best modify those conflicts. Realize you’re going to be less effective if you’re unhappy. When I noticed I wasn’t excited or eager about something, it was time to look in another direction.”

The hallmarks that rang true for Jonrowe in the 1970s still stands today. Zest for adventure and courageous determination meshed with Alaska toughness and the spirit of teamwork make for both an Iditarod star and a Fish and Game legend. “I just love how you can invent yourself to be whatever it is you’ve dreamed of. It was true back in those days, and it’s true now. You just have to work hard at it.”

Interested in working for the Alaska Department of Fish and Game? Check out Your Career in the Last Frontier.

Candice Bressler is a program coordinator for the Alaska Department of Fish and Game and is based in Juneau.

Subscribe to be notified about new issues

Receive a monthly notice about new issues and articles.