Alaska Fish & Wildlife News

December 2009

Tracking Alaska Owls

GPS backpacks provide owl updates

Each day when he shows up at the Alaska Department of Fish and Game in Fairbanks, biologist Travis Booms tracks down the short-eared owls he is studying.

Booms, the department’s non-game biologist, logs on to a Web site that details the movements of 14 short-eared owls he and other biologists are following with the use of tiny satellite transmitters they strapped on the backs of the owls this summer.

“Prior to this, we had absolutely no idea where Alaska short-eared owls wintered,” Booms said.

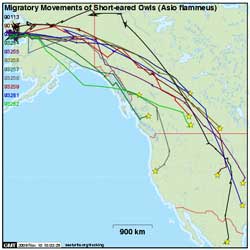

What biologists have seen so far is surprising. The 14 birds are spread out from central Canada down to northern Mexico. Several are in Midwestern states such as Kansas, Nebraska and Colorado, while others are in California, Oregon, Washington and British Columbia. One of the owls is in central Texas at last report, and one is now in central Mexico.

“We expected they would go someplace in the Midwest or Pacific Northwest,” said Jim Johnson, a migratory bird biologist with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service in Anchorage who is collaborating with Booms on the study. “But I didn’t think they’d go as south as Mexico.”

The bird in Mexico is almost 4,000 miles from where it was caught this summer in Nome. The fact the birds have traveled as far as they have is amazing, Booms said.

“Every day you’re watching these birds moving across the continent,” he said. “It really drives home the fact that what happens in northern Mexico effects birds breeding in Alaska.”

Dramatic decline

Short-eared owls are a “species of high conservation concern” in North America, Booms said. Multiple studies suggest that the population of short-eared owls on the continent has declined by 70 percent in the past 40 years, mostly because the grassland habitats they rely on are disappearing.

Short-eared owls have one of the largest distributions of any bird in the world. The only continents on which they don’t exist are Antarctica and Australia. They breed in Europe, Asia, North and South America, the Caribbean, Hawaii and the Galapagos Islands. Birds that breed at northern latitudes, such as those in Alaska, are migratory and move south in the winter.

A medium-sized brownish owl slightly smaller than a raven, short-eared owls are distinguished by their large yellow eyes encircled by black rings and whitish disks of plumage surrounding the eyes like a mask. They have big heads and a short, hooked bill. Short-eared owls are one of the only species of owl to nest on the ground. They are irruptive in that they will flock to areas with high rodent populations.

While not “super common” in Alaska, Booms said the owls have a distinctive flight while hunting that makes them easy to identify, especially because they are one of the more diurnal owl species there is. The birds fly over the tundra or grasslands similar to a butterfly or moth while looking for prey.

“They have a slow, lackadaisical, regular flap,” he said. “Sometimes they’re confused with northern harriers, which have a similar hunting style.”

As far as Johnson knows, there has only been one study done on short-eared owls in Alaska and that was in Barrow about 50 years ago.

“We know practically nothing about these owls in Alaska,” Johnson said. “What we do know is based on anecdotal information.”

It’s been less than six months since biologists put the transmitters on the owls and “we’ve learned a lot so far,” Johnson said.

Tough to find

Biologists were hoping to intercept and catch short-eared owls on their spring migration through the Interior, but that plan didn’t pan out, Booms said.

“We put on about 3,000 kilometers in road miles and failed to catch a single bird,” Booms said.

Fortunately, the scientists heard about an influx of short-eared owls that showed up in Nome in late May. The birds are nomadic in that they follow food sources

“We were starting to wonder if we were going to pull this off when we heard about a bunch of owls in Nome,” Johnson said. “Basically we bought tickets and were out there the next day. It couldn’t have worked out any better for us.”

Biologists used something called a bal-chatri noose trap to catch the owls. The trap, commonly used to catch raptors, consists of a small, hardware cloth box with a live mouse as bait. The mouse is protected in a cage at the bottom of the trap and snares of monofilament fishing line are tied on the top of the box.

The owls get their talons caught in one of the snares when they land to grab the mouse. The traps are weighted to prevent the birds from flying off with them.

“Then you just run up there and grab it,” Booms said. “You can’t let the boxes out of your sight or an owl can get caught and another owl or fox can come by and eat it.”

All the owls were caught between midnight and 6 in the morning, which didn’t pose a problem with the long daylight hours in June.

The fact that Nome has a relatively extensive road system for a Bush village helped make the job much easier, Booms said. They caught all the owls off the road system.

“According to people in Nome, this was one of the highest short-eared owl influxes they’d ever seen in Nome,” Booms said. “We were fortunate enough to be in the right place at the right time.”

Cutting-edge technology

The satellite transmitters, which Booms described as “cutting edge,” resemble a tiny backpack that fits on the birds’ backs. They weigh 12 grams and are solar powered.

“It’s basically a backpack,” Booms said. “The straps are Teflon-coated nylon tubular ribbon so there’s no edge to it. One loop goes over the bird’s head and the other loop goes around the waist and they cross over the center of the breast.

“We fit each harness to each individual bird,” he said. “Each one is a tailored fit.”

For the purpose of the study, only certain sized owls were fitted with transmitters.

“We didn’t want to put transmitters on birds that were too light to carry them,” Johnson said.

Unlike satellite and radio transmitters and collars put on other animals that are rigged to fall off at some point, the transmitters placed on the short-eared owls are meant to be permanent, Booms said.

The transmitters pinpoint a bird’s location to within about 750-feet, Johnson said. They are programmed to transmit a signal 10 out of every 50 hours.

“If it’s cloudy or the birds are roosting during the day where the sun doesn’t hit them we might not get a transmission,” Booms said.

Each transmitter costs about $3,000 and retrieving the data runs about another $2,000.

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service paid for the transmitters this year, and Booms is applying for a grant to continue and expand the study in the next two years, he said.

Migration routes

The birds began moving south in mid to late September. The birds appeared to take two different flyways out of Alaska from Nome. Some traveled through the Northwest and Yukon territories in Canada before heading south to the Great Plains while others followed a more coastal route through Southcentral and Southeast Alaska.

“One owl made it to the Kenai Peninsula and then made an over-water flight of 500 miles to the Stikine River (near Juneau),” Johnson said, adding that the bird is now near Calgary, Alberta.

At this point, biologists don’t know if they are going to stay where they are or keep moving.

“We don’t know if they’ll establish a home range in an area or just drift around for most of the winter,” Booms said. “My guess is they’ll find a place with good food and set up shop.”

Next spring, biologists are hoping the transmitters will tell them if short-eared owls are faithful to their breeding sites.

“One of the biggest questions we have is do they come to the same place in Alaska each year,” Booms said.

Depending on the life of the transmitters, which could be several years in a best-case scenario, biologists will be able to identify the migratory routes of short-eared owls from Alaska, as well as mortality and survival rates.

There is no way to age a short-eared owl, Booms said. The longest-known surviving short-eared owl in North America is 4 years and in Europe it’s 12.

Biologists can continue gathering data as long as the transmitters continue working and the birds don’t die.

“One of the major limiting factors is the life of these batteries,” Johnson said.

“It appears these owls are capable of migrating long distances with these transmitters.”

As winter sets in, biologists expect to get less information on the birds’ whereabouts, in large part because of the nature of the solar-powered transmitters.

“During the winter months when temperatures are cold and the days are shorter, the transmitters don’t charge sufficiently to gather data,” Johnson said. “Several of the owls have gone off the air, and in the spring, we’re hoping they’ll pop back on and we can track them again.”

This article by Tim Mowry was first published in the Fairbanks Daily News-Miner and is reprinted here with permission. Tim Mowry can be reached at tmowry@newsminer.com

The transmitters relay the birds’ locations to a public access website. Booms said anyone can sign-up for daily updates or view near-real time movements at the website directly for free: http://www.seaturtle.org/tracking/?project_id=419

Subscribe to be notified about new issues

Receive a monthly notice about new issues and articles.