Alaska Fish & Wildlife News

March 2025

Stalking Shorebirds on Alaska’s Remote Outer Coast

Researching Elusive Red Knots Part 3

The pilot season was featured in January and the first season in February

Jenell Larsen Tempel picks up the story as the project progresses

We saw dribs and drabs of one to five Red Knots during most of our surveys in our assigned polygons (study areas) during the 2022 pilot season, but the real numbers tended to show up at low tide far out from camp. It seemed like the mud in that area contained a good deal of Limecola balthica, a small clam that is a favorite of Red Knots. At low tide we would look for leg flagged birds and do scat sampling as well as our benthic surveys. The benthic surveys were conducted on randomly selected plots of the intertidal and the goal was to determine the different potential prey items in the bay. Within the plot we conducted four transects, which are straight lines that run parallel to each other. Then at set distances from the shore, along that transect line, we pushed a PVC pipe sediment corer into the mud and pulled it back up. We used a spatula to keep the tube of mud and sand from falling out of the pipe, placed the sediment core in a sieve and then walked to the nearest trickle of water or edge of the tide to wash out the mud. We would be left with tiny clams and marine worms. Each organism was placed carefully in a Whirl-Pak (a small plastic baggie) with a label including the date, exact location, sediment type and organisms present. Once back at camp we would fill these baggies with ethanol to preserve the organisms. Much later the organisms would be sorted in the lab to understand the types of prey that dominate Controller Bay and are available as shorebird dietary items.

Each organism was placed carefully in a Whirl-Pak (a small plastic baggie) with a label including the date, exact location, sediment type and organisms present. Once back at camp we would fill these baggies with ethanol to preserve the organisms. Much later the organisms would be sorted in the lab to understand the types of prey that dominate Controller Bay and are available as shorebird dietary items.

The Song of Knots

The list of challenges was long, but the rewards were also high. We did eventually get to see knots. They showed up a week after us and were generally only in very small numbers, nothing like that flock of 300 that I saw on Okalee Spit the year before. One of the really cool things we got to experience was Red Knots singing. Usually, shorebirds are only heard singing on their breeding grounds. They are absolutely vocal during other times of the year, having their own repertoire of calls when they are flying in a flock, calling out an alarm to others, or squabbling amongst themselves to better their positions while foraging. But the distinct courtship call that Red Knots make is beautiful. It is often described as flute-like. It starts off with see-saw notes low-high, low-high, low-high and then they raise the pitch completely and sing a series of notes that become more rapid and fluid. I could image them on the tundra singing the same song and dipping their tails up and down in courtship 10,000 years ago. To be able to experience what few people ever see or hear, because it takes place on their dispersed Arctic breeding grounds, was really special. They must have been practicing their dances and getting their voices ready, bobbing their tails up and down as they sang circling one another. On one occasion I even woke in my tent to the sound of them streaming overhead while singing their courtship song, the sunlight streaming through the alder branches above me. It is my most peaceful memory of my time out there that year.

Lessons learned

I probably don’t have to tell you that we didn’t return to the bear infested Edwardes Camp the following year in 2023. We also never set up another camp on Kanak Island and in fact I had that crew move locations completely during the 2022 field season because again, there were no knots over there, and the weather made surveying by boat to the other side of the bay impossible. The Kanak crew moved to the mouth of the Bering River, which turned out to have promising Red Knot habitat and a few days with flocks numbering 300-500 and one as great as 1,000! The crew camped out on Okalee Spit had the most success, saw consistently more birds, and recorded the most leg flags. In 2022 we recorded a total of 13 flags, but only nine were legible. The number of resights was too low to conduct the mark-resight methods I  planned to employ for estimating population size. Moreover, the leg flags that observers in the field recorded did not match the records of bands put out, resulting in a big issue of not knowing if these reports were the result of observer error, or if folks doing the banding were not submitting the band data to the federal Bird Banding Lab. This was problematic because we needed to be certain that the flags recorded were correct and could be correctly re-identified by another observer in the field. Our methods relied on that.

planned to employ for estimating population size. Moreover, the leg flags that observers in the field recorded did not match the records of bands put out, resulting in a big issue of not knowing if these reports were the result of observer error, or if folks doing the banding were not submitting the band data to the federal Bird Banding Lab. This was problematic because we needed to be certain that the flags recorded were correct and could be correctly re-identified by another observer in the field. Our methods relied on that.

Although we could not obtain an abundance estimate in 2022, we gained a slew of valuable information. We found that only working to survey birds bracketing the high tide wasn’t working. Sometimes it was beneficial to work them from the waterside when the tide was falling as they moved closer to you, sometimes you had to factor in the wind. Sometimes the ideal tide was very late or very early and didn’t allow for enough daylight or a long enough survey. We loosened up our survey timing. As long as each polygon was surveyed with the same amount of effort daily, the timing was a bit arbitrary. I took the count data we collected throughout the bay and worked with a GIS analyst to map out the Red Knot hot spots. Clearly there was a pattern that observers noticed in the field about where the knots liked to forage and areas where we never saw them. We mapped out the habitat use from these surveys and three obvious hot spots jumped out at us: the western half of Okalee Spit, the mouth of the Campbell River, and the mouth of the Bering River along the eastern edge. It was easy to decide where to put in camps for next year. We would focus on having larger crews at these frequently used locations. We would scrap the middle of the bay completely. The other decision I made that was a game changer, was to hire on dedicated photographers.

took the count data we collected throughout the bay and worked with a GIS analyst to map out the Red Knot hot spots. Clearly there was a pattern that observers noticed in the field about where the knots liked to forage and areas where we never saw them. We mapped out the habitat use from these surveys and three obvious hot spots jumped out at us: the western half of Okalee Spit, the mouth of the Campbell River, and the mouth of the Bering River along the eastern edge. It was easy to decide where to put in camps for next year. We would focus on having larger crews at these frequently used locations. We would scrap the middle of the bay completely. The other decision I made that was a game changer, was to hire on dedicated photographers.

In 2022 a Ducks Unlimited Intern, named Blake, was working for the summer with my Forest Service collaborator. He came out to participate in the Red Knot work and was stationed out at the Bering Camp for 10 days. Photo: From left, Fernando Angulo, Blake Richard, Aaron Bowman and Lyda Rees at the edge of the frame taking the photo.

In 2022 a Ducks Unlimited Intern, named Blake, was working for the summer with my Forest Service collaborator. He came out to participate in the Red Knot work and was stationed out at the Bering Camp for 10 days. Photo: From left, Fernando Angulo, Blake Richard, Aaron Bowman and Lyda Rees at the edge of the frame taking the photo.

He happened to be a professional photographer and took beautiful pictures of Red Knots foraging in the intertidal and even captured some crystal clear images of leg flagged birds. Unfortunately, some of these leg flags were completely blank (had no  alphanumerics or the ink was worn off), or so they appeared while in the field. But using the amazing photographs that Blake took, we could zoom in on the images and actually make out the engraved letters and numbers and determine that the ink had washed away. Having the photographs converted the flagged bird from being a useless but unique sighting to a now-useful piece of data and a bird that could be identified and resighted again so long as we had a decent photo of it. This completely changed my thinking about what type of people I should recruit for my field season next year -photographers. My hope was that by having permanent photographic evidence of the leg flag alphanumerics it would eliminate any observer error issues.

alphanumerics or the ink was worn off), or so they appeared while in the field. But using the amazing photographs that Blake took, we could zoom in on the images and actually make out the engraved letters and numbers and determine that the ink had washed away. Having the photographs converted the flagged bird from being a useless but unique sighting to a now-useful piece of data and a bird that could be identified and resighted again so long as we had a decent photo of it. This completely changed my thinking about what type of people I should recruit for my field season next year -photographers. My hope was that by having permanent photographic evidence of the leg flag alphanumerics it would eliminate any observer error issues.

Lastly, we adjusted our season to be one week later to better capture the peak migration. This decision was the toughest to make. Migratory shorebirds are notoriously difficult to study because they are inconsistent. They can  arrive weeks earlier or later in some years, and while some species have high site fidelity, others appear to use a variety of sites without any particular pattern, skipping some sites altogether in some years. I spent weeks trying to gather any data I could on historical peak migration dates of Red Knots in the general area of the Copper River Delta. I spoke with local birders, used data from eBird and worked with other biologists that had done GPS tracking on the species or recorded peak numbers in coastal Washington, the nearest known large stopover site. Using these bits of information across multiple years, I determined that the peak migration could be as early May 8, or as late as May 23. I decided on a season spanning May 4-27. We could always pull camp early, but we couldn’t do anything about arriving too late and missing them.

arrive weeks earlier or later in some years, and while some species have high site fidelity, others appear to use a variety of sites without any particular pattern, skipping some sites altogether in some years. I spent weeks trying to gather any data I could on historical peak migration dates of Red Knots in the general area of the Copper River Delta. I spoke with local birders, used data from eBird and worked with other biologists that had done GPS tracking on the species or recorded peak numbers in coastal Washington, the nearest known large stopover site. Using these bits of information across multiple years, I determined that the peak migration could be as early May 8, or as late as May 23. I decided on a season spanning May 4-27. We could always pull camp early, but we couldn’t do anything about arriving too late and missing them.

A knock-out year

Armed with a season of experience and a year of reflection we began again. I had many returning crew members,

We kicked off our work right at the start of the annual Copper River Delta Shorebird Festival. I had many returning crew members, and as it turned out, 2023 proved to be a knock-out year. Between the two camps we recorded 45 leg-flagged individuals and nine of them were seen across multiple days. Thanks to our amazing photographers, we had photographic evidence of every single one! We had just enough data to run our abundance estimate model. The results are still preliminary but suggest

Back at the lab

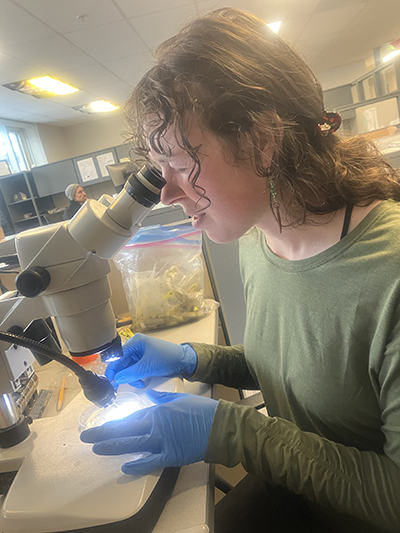

During the off-season I worked with two University of Alaska Southeast college students that were interested in

The results were not entirely surprising. Other studies that looked at the benthic community further north of Controller Bay, along the mouth of the Copper River also found low species diversity, though their numbers were higher for polychaete worms and amphipods. While we saw most species of shorebirds in the field pulling up polychaete worms (especially the black-bellied plovers and dunlin), none of our observers saw Red Knots physically eating polychaete worms. (Photo of a dowitcher flying with a polychaete worm in bill) Additionally, there was an event in 2022 when many shrimp washed up. It created a buffet for shorebirds, gulls and terns, however, the Red Knots did not seem be partaking in the feast. It

Shorebird foraging strategies

Part of this could have less to do with the bird’s preference and more to do with their foraging strategy or how they

Have you ever noticed that the bigger birds with long legs and long beaks are usually seen foraging in deeper water, while the birds with shorter legs and shorter bills are moving quickly across the sand pecking at things rather than

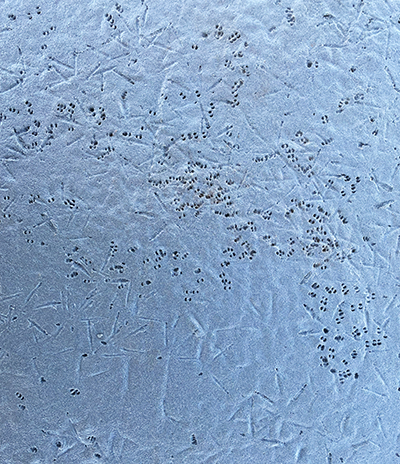

Scientists did experiments with Red Knots in captivity and discovered that in wet sand they can successfully find stones, buried centimeters under the surface. This was surprising. Unlike living animals, the stones are the same temperature as the sediment, do not move, produce no smell and have no electromagnetic field. This indicated that knots were not using any of the senses or mechanisms known in

Given all this information, it makes sense that knots specialize on bivalves, it is what they have evolved to locate, but we know that they are capable of eating other prey and taking advantage of locally abundant prey. Red Knots on the east coast of the US are famous for eating horseshoe crab eggs, which are soft and squishy and are found on top of the sand not buried under it. Researchers in Mexico have reported that Red Knots there may feed

Environmental DNA

eDNA has been employed for a great variety of uses. You may have heard of it being used to determine the species that are found in a certain body of water, or you may have read a previous Alaska Fish and Wildlife News article on how some of our biologists are using it to study harbor porpoises. Although it is often thought of as being used for water or sediment, it can likewise be applied to fecal matter. However, it is important to note that eDNA is not a silver bullet. It often requires having known prey items for the species in question and can be prone to issues like cross-contamination. As with everything else in 2022 we had some issues with our eDNA analysis. In order to save costs and increase the amount of samples we could collect we attempted to sample five Red Knot poops per vial. To do this, two observers went out together outside of the survey time and watched a small flock until one bird deposited a scat on the mudflats. One person kept the little bird scat in view of their scope. Once the birds moved on, or before the tide washed away the scat, the other observer went out to retrieve it taking directions from their partner at the scope. This was not as straightforward as it should have been. For one thing the bay is a shorebird mecca. There are bird poops everywhere. For another, the scale can be quite hard to judge. For example, it might appear to the person at the spotting scope that you are standing right on top of the scat, but you are looking down seeing no scat. In fact, you are 3 feet or 6 feet away  from where the scat was deposited. Most challenging was the wind. Even as your partner yelled at you and waved their arms wildly to the left or right it was hopeless to locate a pinky nail sized bird scat among dozens of others without the radios in the wind. And sometimes you were so focused on collecting the scats before an incoming tide, that by the time you turned back to where you left your gear and bike, it was all underwater. Above, the author recovers her bike and gear after it is swamped by the incoming tide.

from where the scat was deposited. Most challenging was the wind. Even as your partner yelled at you and waved their arms wildly to the left or right it was hopeless to locate a pinky nail sized bird scat among dozens of others without the radios in the wind. And sometimes you were so focused on collecting the scats before an incoming tide, that by the time you turned back to where you left your gear and bike, it was all underwater. Above, the author recovers her bike and gear after it is swamped by the incoming tide.

Although we did our absolute best to select only Red Knot fecal samples, about half of our samples came back indicating that there was also DNA present from other shorebird species (i.e., the sample was 50% REKN, 25% Dunlin and 25% Black-bellied Plover). These samples (the whole vial) had to be discarded because we could not differentiate what proportion of the prey these other species ate versus the knot. Some of our samples also contained contamination from the lab as species appeared in the results that were not even present in the area. And then for the ones that were ok, the lab didn’t have a prey library that was comprehensive enough to match any of the DNA in the fecal matter to prey species. This was  unforeseen, even by the lab manager. This meant we would need to physically collect the potential prey items from the bay. Something we didn’t do. It was disappointing. As with everything else, we made some changes for 2023. I found a new laboratory at a university that had experience extracting fecal DNA from Red Knots on the east coast and switched labs. I also found a biologist that was an expert in shorebird fecal collection methods. Alan could look at a bird track in the mud and tell you what species made the track and follow the tracks to identify scats. He was a one man show. No spotter, no shouting into the wind. While we focused on perfecting the survey protocol, getting those leg flag shots, he dedicated part of each day to carefully observing and tracking Red Knots and doing scat sampling.

unforeseen, even by the lab manager. This meant we would need to physically collect the potential prey items from the bay. Something we didn’t do. It was disappointing. As with everything else, we made some changes for 2023. I found a new laboratory at a university that had experience extracting fecal DNA from Red Knots on the east coast and switched labs. I also found a biologist that was an expert in shorebird fecal collection methods. Alan could look at a bird track in the mud and tell you what species made the track and follow the tracks to identify scats. He was a one man show. No spotter, no shouting into the wind. While we focused on perfecting the survey protocol, getting those leg flag shots, he dedicated part of each day to carefully observing and tracking Red Knots and doing scat sampling.

Next month: The Big Picture – the final installment brings the entire project together with an overview of what was learned.

More on eDNA, AFWN article from 2024 Harbor Porpoises Highlighted for Surveys - New tools aid study of secretive marine mammals

Crew members returning to camp on a rare sunny day in Contoller Bay.

All photos ADF&G, by Jenell Larsen Tempel, Blake Richard, Fernando Angulo, Ria Smyke, Tory Rhodes, Nick Docken, Arin Underwood, Evan Ward and Lyda Rees.

The Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) reviews programs and projects to ensure animal welfare. IACUC protocol numbers for work done for 2022: 0107-2022-25, for 2023: 0107-2022-25

Red Knot calls and sounds (The second-to-last song in the list, recorded in Alaska on June 22, 2014, by Andrew Spencer, is particularly cool.)

More on the Threatened, Endangered and Diversity Program at ADF&G

Subscribe to be notified about new issues

Receive a monthly notice about new issues and articles.