Alaska Fish & Wildlife News

August 2024

Hunters help bear management and research

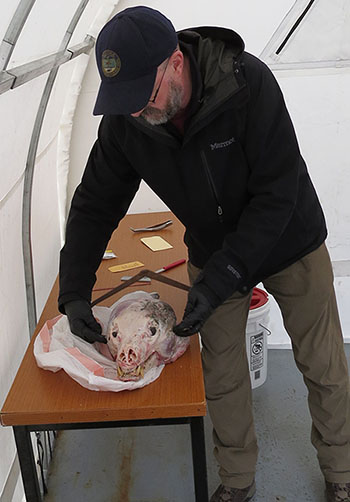

On a overcast Monday morning, Juneau hunter Dorian Hobbs shared the details of his successful weekend bear hunt with biologist Carl Koch. Wildlife biologists in Alaska talk with hunters all the time, but this rendezvous at the “sealing shed” in the parking lot of the Southeast Alaska regional office was more than a chat - Hobbs was providing valuable data to a wildlife manager.

Hobbs opened a black plastic bag and tugged out the edge of a thoroughly salted black bear hide, filling the shed with the smell of damp fur and fresh meat. He told Koch he and his friends had taken a boat to a semi-remote area and found several bears.

“We saw him on the beach and I went into the woods and they were everywhere,” he said. “We saw five on the beach in an hour.”

Koch pulled some hair for a DNA sample. Hobbs handed him the bear skull – the entire skinned head – and Koch measured it with huge calipers. As they talked, he pulled a small premolar tooth so the bear can be aged (the tooth is cross-sectioned and annual growth can be counted like tree rings). Hobbs told Koch he had hunted the bear, his first, because he wanted to eat it. He was giving the hide to a friend for tanning, but keeping the skull to clean and display. He was hoping for the best for bear meat. “If it turns out good, I will continue to hunt bears,” he said. “I don’t shoot what I don’t eat.”

Koch recorded the location of the hunt, how he got there, and the effort (the number of days hunted on this trip). He checked his license and documentation, and looked over the hide to check the claws and proof of sex. Another hunter stopped by with a brown bear and waited as they finished.

Successful bear hunters in Alaska, resident and nonresident, are required to bring the hide and the skull of all bears harvested to a Fish and Game office for sealing. It’s called sealing because back in the day a seal was affixed to the hide and skull, these days it’s a locking metal tag or band. Harvest locations are not shared with the public, but general statistics are available.

Sealing data allows wildlife managers a view of trends over time, often many years. The hunt effort offers insight into the status of the bear population. If hunters are spending 10 days to get a bear, versus four or five in previous years, that may be an indication that fewer bears are available.

Biologist Charlotte Westing, based in Cordova, manages black bears in Prince William Sound. She said knowing the age of bears harvested is particularly useful.

“Biologists look at age data for insights on what the population has done and what it’s going to do,” she said.

Prince William Sound has experienced years where cub survival was exceptionally low, such as 2011, and that’s reflected in the harvest data. In subsequent years that age class (as determined from that extracted tooth) is almost non-existent in the harvest. For a wildlife manager, that also has an implication for adult female bears. Since it is illegal to harvest a sow with cubs, a bear with cubs on her heels is protected. A solo female may be harvested – eliminating a bear that could have helped rebuild the population and coinciding with a time when the population is experiencing a downturn in recruitment. And that might also coincide with a period of increasing hunting effort – more hunters hunting fewer bears.

“People are always wondering what we can learn from skull size and teeth data,” Westing said. “Knowing the age of bears harvested, and being able to look at how a specific age class, like how a big year for cub production moves through the harvest over multiple years, is important and useful.

Bill Dunker is a state wildlife biologist on Kodiak Island, home to Alaska’s famous Kodiak brown bears. He said sealing bears allows wildlife managers to maximize the amount of information that can be gained from a harvested animal and provides a good opportunity to meet with hunters.

“I love the sealing process,” he said. “I get to see the bears, talk with hunters, ask them, ‘what did you see, where did you go, what were the conditions on the ground?’”

He said there have been a number of roe-on-kelp herring spawning events in recent years on the Kodiak Archipelago, which provides a major food source for bears in the spring. Hunter reports of bears cruising the shoreline and congregating in specific areas is good information, “drivers of harvest,” and insight into how the hunt unfolds in a given year.

Dunker said Kodiak biologists are hoping to use tissue samples for a “close kin mark recapture,” a technique that provides insights into population abundance. They’re also planning to do stable isotope analysis of hair samples, which provides insights into diet composition throughout the year, and the timing of the availability of food resources – such as that herring roe in the spring. As the strand of hair grows over the course of a year, the pulse of a dietary staple such as salmon in later summer, and winter fasting during hibernation, can be detected in the hair.

Biologists also look at how sealing data correlates with data from other sources, such as anecdotal information – observations by biologists and hunters, and even wildlife watchers.

State bear biologist Anthony Crupi collaborated with a graduate student looking at changes in black and brown bear populations in northern Southeast Alaska. DNA from tissue samples provided insights into distinct population groups for both species in the region, and researchers looked at how barriers like fjords, waterways and icefields affected the bears’ movements and “gene flow.” Close to 30 years of harvest records provided insights into shifts in the two species’ densities in specific areas – how brown bears might be increasing in areas where black bears had previously been found in greater numbers.

Brown-Grizzly bear hunting in Alaska

Bear Hides: Skinning and Field Care

Prince William Sound bear management

Subscribe to be notified about new issues

Receive a monthly notice about new issues and articles.