Alaska Fish & Wildlife News

July 2024

Coastal Cutthroat Trout

The Phantom of Prince William Sound

My First Coastal Cutthroat Trout

Having grown up in Alaska, I’ve had the privilege of experiencing some of the world’s finest freshwater angling opportunities. Over the years, I've notched several 32-plus inch rainbow trout, Arctic Grayling over 20 inches, handfuls of (as I describe) “Dinosaur Dolly Varden”, and a decade-long streak of completing the Five Salmon Family Challenge; each catch has been a testament to the rich aquatic life that thrives in Alaska’s waters. While this might seem like opportunity for me to brag about some of my ADF&G Trophy Certificates, it is more meant to highlight a species that had eluded me for over two decades as an Alaskan resident– coastal cutthroat trout.

Being obsessed with all things fish-related since an early age, I studied the Alaska Trophy Fish Records more in depth than most school subjects in grade school. I could recite the location, date, angler name, and even weight- down to the ounce- for the record fish across every Alaska sport fish species. If you asked me “what is the largest rainbow/steelhead trout caught in Alaska?”, I would quickly respond with “42 pounds, 3 ounces” followed by way more information than you would ever hope to know about 8-year-old David White’s record catch from Bell Island in 1970. In my studies of Alaska fishes, there was one fish in the record books that piqued my curiosity the most and that was the coastal cutthroat trout. I remember asking my father, “where can I catch a cutthroat trout?” Disappointingly, he replied “they aren’t here,” and by “here,” he was referring to our home in Southcentral Alaska. As a result, I chalked-up cutthroat trout as species reserved for those that lived in Southeast Alaska, but looking back that couldn’t have been more wrong.

I began my career with ADF&G in 2014 as a senior in college. Ahead of my start date, I dove into as many books about the areas that I would be working in, which included Prince William Sound. To my surprise, each brochure, fishing book, and report time-and-time again referenced opportunities for coastal cutthroat trout in Prince William Sound. This flipped my understanding of the species upside-down, but in doing so, it fueled a fire. This whole time I hadn't realized that coastal cutthroat trout resided right in my backyard and now I was eager to encounter this species.

In my second summer, I was tasked with accompanying Area Management Biologists Dan Bosch and Mike Thalhauser on a five-day research trip in Prince William Sound to conduct deepwater release studies on rockfish species. This required us to catch a variety of species of rockfish, assess them for barotrauma and release them to depth-of-capture captive in 15-gallon barrels; this was meant to simulate deepwater release. After 48 hours, we would retrieve those barrels and assess whether those rockfish survived or not. Impressively, nearly every single rockfish survived, but that’s a conversation for another day.

During the 48 hours while the rockfish were submerged, we would spend time checking regulatory signs, building an outhouse, and completing the usual day-to-day field camp tasks at the ADF&G cabin in Eshamy Lagoon; most of these tasks wouldn’t fill 48 hours, let alone a full workday. To fill time, Dan and Mike often preferred to go on a hike, pick berries, or watch for wildlife; not me though, I always have fish on the brain.

Fortunately for me, during my pre-employment studying, the literature referred to Eshamy Lake as an excellent opportunity to catch coastal cutthroat trout. I knew this heading into the trip, so I snuck my 5-weight fly rod and every fly under the sun into my duffle bag before we left the office. As Dan and Mike went off looking for river otters or some other mammal without fins, I opted to stay back at the cabin with ulterior motives- catching a cutthroat. Peering out over the mouth of Eshamy Creek from the deck of the cabin, I could see school-bus sized schools of salmon smolt. Every few minutes, the school would part like the Red Sea as a harbor seal would swoop through and grab mouth full of juvenile sockeye. In doing so, the broken-up school would reveal large flashes that were much bigger than a smolt but smaller than an adult sockeye. “Bingo!”, I thought, “those have to be cutties.”

To start, I tied on a handmade mylar fry pattern; an abomination in the eyes of most purist flyfishers, I know. But any Alaskan fly angler is well-aware that (1) being a purist doesn’t always catch you fish and (2) it is hard to beat a “mylar fry” for imitating salmon fry and smolt. I slung my first cast and my fry pattern landed just on the opposite side of the school of salmon smolt. It was almost instant, boom! My line was taught, and I could see my flashy cutthroat trout slowly making its way towards me with much resistance. Standing on the barnacle and algae-covered boulders, I slid the fish into my hand net. I could see the trout-shaped prize; bright chrome, pink spots, and white fins… “Wait, pink spots?”, I thought. To my dismay, I had landed a sea-run Dolly Varden. Don’t get me wrong, I have a strong appreciation for Dolly Varden and often make dedicated Dolly Varden excursions, but my eye was one prize. I made my second cast, Dolly. Third cast, Dolly… that went on for a few hours. Finally, Dan and Mike called me up to the cabin for dinner, but I was determined; I still don’t remember to this day whether I went up to eat.

Twilight began to set in, which in the narrow mouth of Eshamy Creek happens quickly as the Prince William Sound rainforest blocks out sunlight. I knew my opportunities were numbered. The tide pushed in and forced me further into the creek, so I was no longer fishing tidal water but rather a rushing creek. I watched closely behind the water pillowing over the boulders, and in an eddy, I noticed something peculiar- a green and orange flash. It caught my attention because it was so distinct from the bright flashes of the endless Dollies before me. I roll-cast towards the boulder and immediately the turbulent water carried my fly away from the eddy and this mysterious flash. I knew there was too much moving water between me and this small pocket of water where I needed to present my fly. I marched upstream, carefully calculating the angle and distance where, when swung, my fly would spend the most time in this narrow window. I false cast until I knew I had the precise location for my fly to land, and then I committed. My fly line was just over the whitewater-covered boulder and my leader just beyond it. As the current dragged my line down, I knew my fly was in the zone, albeit briefly, but that was all it took.

Instantaneously, my fly line and the end of my leader that was cast into freshwater had zipped down into the saltwater lagoon that I had previously been fishing, and with it, my phantom fish. The fight was different: this fish pulled drag and made bulldog-like dives. Although, it wasn’t long before I claimed my prize and it hit the net. Immediately, I could see the leopard printing on every millimeter of this fish and the telltale, orange slash on its throat. I was graced by my first coastal cutthroat trout; not in Southeast Alaska, mind you, but less than 75 miles from my childhood home in Southcentral Alaska. For an angler, there are few moments that lead you to pack it up and end a high note, skipping the “one more cast” routine; for me this was it. I slide my rod into my quiver, snuck into the cabin, and climbed into the top bunk of the cabin. I slept well that night with the thought of cutthroat trout dancing in my head.

I still laugh to this day that it was rockfish, that ironically, brought me to my first coastal cutthroat trout.

Coastal Cutthroat Trout 101

Coastal cutthroat trout are a member of the genus Oncorhynchus. In fact, their scientific name is Oncorhynchus clarkii clarkii, receiving their namesake from William Clark of “Lewis and Clark,” the American explorers. The second clarkii in the coastal cutthroat trout’s scientific name indicates that they are subspecies of cutthroat trout. There have been as many as 14 described subspecies of cutthroat trout, which has been subject of debate. Regardless, coastal cutthroat trout are the only subspecies of cutthroat trout to reside in Alaska. Formerly, cutthroat trout were assigned to Salmo genus, which contain species like brown trout (Salmo trutta) and Atlantic salmon (S. salar). It wasn’t until fairly recently (1989) that taxonomists discovered that cutthroat and rainbow trout were more closely related to Pacific salmon, hence their classification as Oncorhynchus.

Coastal cutthroat trout are distinguishable from rainbow trout (O. mykiss) by the red or orange streaks under their lower jaws, hence the name "cutthroat." Overall, they tend to be smaller than their rainbow and Dolly Varden counterparts, typically ranging from 12 to 18 inches in length, although larger specimens have been recorded (I’ll come back to this later). Their bodies are adorned with spots, and their coloration can vary from silvery to olive green, blending perfectly with their surroundings.

Coastal “cutties” can exhibit various life histories. Coastal cutthroat can migrate to and from saltwater just like some populations of rainbow trout; however, sea-run coastal cutthroat did not receive a cool name like “steelhead,” which was assigned to sea-run rainbow trout. While coastal cutthroat can be anadromous, they do not die after they spawn; this is referred to as “iteroparous,” meaning they can spawn multiple times. Similar to rainbow and steelhead trout, coastal cutthroat trout are spring spawners, which has led to spawning protection during April and May in some regions of Alaska.

Coastal Cutthroat and where to find them

Coastal cutthroat trout range from the Eel River in California to Alaska. Coastal cutthroat are highly distributed and well-documented throughout Southeast Alaska with many known populations near larger towns such as Craig, Juneau, Sitka, Ketchikan, and more. The Coastal Cutthroat Trout Mapper is an excellent resource to find where cutthroat have been located throughout their range.

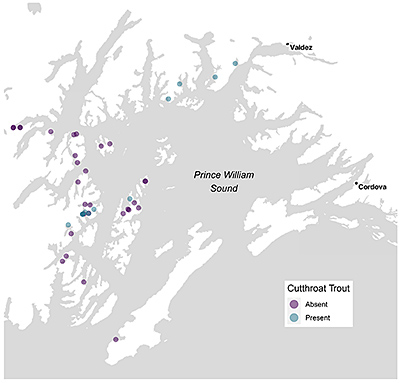

If we turn towards Southcentral Alaska, Prince William Sound, which represents both the northern and westernmost range for coastal cutthroat, documentation is much spottier. Referencing the Anadromous Waters Catalog (AWC), one can find that nearly every stream in Prince William Sound is documented with pink and chum salmon and in some cases, coho and sockeye salmon; however, it is very rare to find coastal cutthroat trout documented in the AWC. In part this is because some coastal cutthroat trout in Prince William Sound are only freshwater residents in lakes and streams, and are not anadromous, so these populations won’t necessarily be represented in the AWC. More commonly, they are not represented in the AWC because we simply just don’t know that the populations exist. There is thought to be over 750 anadromous waterbodies in Prince William Sound, and of which, less 10% had been sampled for coastal cutthroat trout prior to 2020.

Fortunately, our understanding of the rivers and lakes they inhabit in Prince William Sound is still growing. As a part of project in 2021-2023, ADF&G partnered with the Western Native Trout Initiative and anglers (just like you) to better document where this species inhabits at the fringe of their range. Anglers possess a wealth of knowledge and intimate experiences in remote locations of Alaska that can teach us so much about species. ADF&G tapped into that angler knowledge via social media, outreach events such as the Great Alaska Sportsman Show, and fliers to garner information on the whereabouts of coastal cutthroat trout in Prince William Sound. The results were impressive! Around 15 anglers came forward with information from 12 different locations in Prince William Sound that are home to coastal cutthroat trout populations that were previously unknown to science.

For three years, we “sampled” (in other words, fished) 57 new locations for coastal cutthroat trout. But we didn’t just throw ‘darts at a dartboard’ when picking those sites to sample. We used characteristics from the places that we knew had cutthroat trout from previous studies and the locations suggested by anglers. As a result, we documented 19 new populations of coastal cutthroat trout in Prince William Sound. You might think “19 out of 57, that’s only finding one population of cutthroat populations out every three locations sampled,” and in which I’d respond, “well, it's still better than the MLB batting average.” You can only glean so much information looking at map and trying to predict where this phantom species might be, but truth be told, Prince William Sound isn’t that simple. For example, during the 1964 Good Friday Earthquake sections of land in Prince William Sound rose over 50 feet instantaneously, cutting off upstream migration for many streams. In the end, we figured out three main characteristics of a watershed that make it more likely harbor coastal cutthroat trout in Prince William Sound:

1. Watersheds with lakes- The more lakes, the better; coastal cutthroat trout need overwintering habitat that is safe from predators and requires low energy. The ocean tends to have lots of predators and streams tend to require a lot of energy, so a safe bet is to spend the winter in a lake.

2. Watersheds with low gradient- Coastal cutthroat trout need to colonize lakes and streams by migrating from one lake or stream to another. If it is too step, they cannot climb it and establish a population. This is why earthquakes and glacial static rebound play a big role in a species' ability to colonize a new system.

3. Watersheds near other cutthroat populations- This one sounds almost too obvious, but there is a reason why! Coastal cutthroat trout have been known to migrate only up to 100 miles in saltwater, which pales in comparison to the migration of Pacific salmon and steelhead. It’s a scary ocean with lingcod, tiger rockfish, and orcas- oh my! For a small sea-run trout species, it’s safer to stay home or not migrate too far.

During the study, we were able to push the known range of coastal cutthroat trout further five-miles to the west and from one spectacular angler report pushed the range about five-miles north. It doesn’t seem like much, but consider that coastal cutthroat trout do not like to stray too far from home. ADF&G continually receives cutthroat trout sighting from further west outside of Prince William Sound and as far west as Seward. It might seem like stretch, but we with enough time and exploration by anglers, it is a possibility. We are quarter of the way into the 21st century still learning the simplest part about a fish’s biology- where they live.

Trophy Coastal Cutthroat Trout

The current Alaska state record cutthroat trout was caught in 1977 from Wilson Lake near Ketchikan and it weighed 8 pounds, 6 ounces; that is impressive for any trout species, but especially a coastal cutthroat trout. Some might even consider that tiny compared to the coastal cutthroat trout’s cousin, the Lahontan cutthroat trout, which can tip the scale at well over 20 pounds. Since the creation of the Trophy Fish Program, there have been around 100 trophy coastal cutthroat trout submitted to ADF&G for trophy certification; of those, only one has been from Prince William Sound.

The sole Prince William Sound trophy coastal cutthroat measured 22.5 inches from the Martin River, a tributary of the lower Copper River near Cordova; it was estimated to weigh about 5 pounds. This is far above the average of around 12 inches with a range of 6-18 inches that we encountered during the three-year study. The Martin is an unusual river system as it is home to coastal cutthroat trout and both resident and sea-run (steelhead) rainbow trout, which can hybridize. A cutthroat and rainbow trout hybrid is also known as a “cutbow”, which tend to be larger than a coastal cutthroat trout. Determining whether this Prince William Sound trophy was a cutthroat or “cutbow” is impossible without a tissue sample to analyze its genetics.

Regardless, pursuing coastal cutthroat trout in Prince William Sound is not for trophy chasers or “hog hunters.” Fishing for coastal cutthroat trout is more about the journey: it is about stumbling across century-old, derelict canneries; it is about picking seemingly endless, vibrant salmon berries; it is about burning time while your shrimp pots are soaking; and for some, it is about getting to dance with a phantom for your first time.

Donnie Arthur is the assistant area management biologist for Anchorage, Prince William Sound and the North Gulf Coast.

Subscribe to be notified about new issues

Receive a monthly notice about new issues and articles.