Alaska Fish & Wildlife News

June 2024

Salmon Ocean Ecology Program

When you think of projects designed to monitor salmon populations in Alaska, what comes to mind? Maybe a weir or a counting tower, a sonar project, or a spawning grounds survey? While these activities are crucial for sustainably managing our salmon populations, they share a common focus: they occur in the freshwater stage and monitor the spawning phase of salmon. However, there is another crucial part of the salmon life cycle – their time at sea! Compared to the freshwater stage, our knowledge about this period of their life is much more limited.

As salmon enter the marine environment, they reach a particularly critical phase of their life known as the juvenile stage. During this stage, they face significant challenges to their survival. Assessing and monitoring salmon during this crucial period is the core mission of the newly created Salmon Ocean Ecology Program (SOEP) at the Alaska Department of Fish and Game. Although the program is small, with just three scientists, we collectively bring over 40 years of experience in the Bering Sea and other marine research.

Given that we are currently a three-person team, our work relies heavily on partnerships and experience gained long before SOEP was established. Over the past decade, our researchers have collaborated with other ADF&G staff, federal agencies like NOAA, universities, and non-governmental organizations to conduct marine surveys to better understand the abundance, distribution, stock of origin, diet, and health of juvenile salmon. Additionally, these surveys employ various methods to examine the ecosystem, including the physical and chemical properties of juvenile salmon habitat, the food available to them, and their predators.

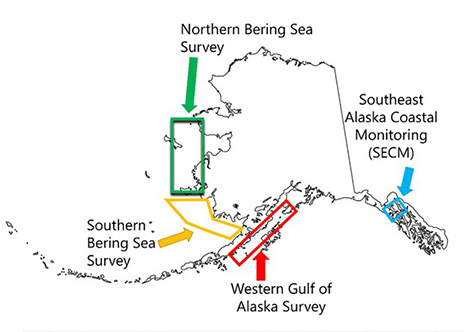

SOEP scientists assist ADF&G regional staff to support two longstanding surveys within Alaska – the northern Bering Sea survey and the Southeast Alaska Coastal Monitoring Survey (SECM). The northern Bering Sea survey primarily focuses on learning more about juvenile Chinook and chum salmon of Yukon and Norton Sound origin, and building adult return forecast models for these species, whereas SECM is primarily focused on forecasting pink salmon harvest in Southeast Alaska. These surveys take place during summer when juvenile salmon are distributed in the nearshore environment and the upper region of the water column – their prime habitat. These surveys use large marine vessels that can handle rougher seas and effectively tow a 600-foot net for 30 to 60 minutes at 3 to 5 knots speed. The net, a surface trawl, has a conical shape that guides the fish to the smaller-meshed end of the net called the codend. After a tow, the juvenile salmon and other fish are brought to the surface, sorted by species, and retained for various studies aimed at giving us better view of the first year of salmon life at sea.

The insights gained from these marine surveys have proven invaluable. In Southeast Alaska, researchers can predict, with a level of acceptable error, the number of pink salmon to be harvested the following year based on the current year’s juvenile abundance, their condition, and environmental conditions. This allows managers, processors, and stakeholders to plan operations accordingly. Similarly, in the northern Bering Sea, there are strong correlations between the abundance of juvenile Chinook salmon that survive their first summer at sea and the numbers that return as adults to the Yukon River. This indicates that the period from the adults’ return through their offspring’s hatching and early life in freshwater and marine environments is crucial in influencing adult return patterns for Chinook salmon - more so than mortality sources after the first summer, such as competition, bycatch, or predation. This strong relationship also allows researchers to predict Chinook salmon returns up to three years in advance!

In contrast, Yukon chum salmon have not shown as strong a relationship between juvenile abundance and adult returns, suggesting that later marine factors may have driven the lower returns observed over the past few years. The most plausible explanation for this finding is the impact of large marine heatwaves in the Bering Sea and North Pacific Ocean during the juvenile years associated with those lower returns (2016–2019). Compared to cooler years, juvenile chum salmon collected during this warmer period had very little stored energy, and more of their stomachs were empty. This combination likely spelled disaster for chum salmon heading into their first winter at sea when food is particularly scarce.

Our marine surveys also provide valuable information about salmon predators. You may recall a previous Alaska Fish and Wildlife News article that detailed our program’s salmon shark tagging efforts. Occasionally, the surface trawl will catch a salmon shark and we use satellite and archival tagging technology to track those sharks and better understand how they overlap with salmon distribution. To date, eight salmon sharks have been tagged as part of this program. We also document predator scars and marks on juvenile salmon as they are brought aboard so that those can be identified. Additionally, we collect water samples for environmental DNA analysis, which can tell us what predators were in the vicinity of our survey stations. This is important information because our nets are not efficient at sampling large predators, nor would we want to catch them! All these findings, for juvenile salmon along with information on their predators, are just a few examples of the previously unavailable insights we can gather from marine surveys.

So, what’s next for SOEP? Taking what we have learned from the northern Bering Sea and SECM surveys, we will be expanding juvenile salmon surveys into other important regions of the state. Our current focus is on implementing surveys in the southern Bering Sea, which will provide new insights into Kuskokwim River and Bristol Bay salmon stocks, and in the western Gulf of Alaska for Cook Inlet and Chignik salmon stocks.  There are questions and concerns for salmon stocks from these regions, and we have good adult return abundance estimates from ADF&G projects operating in freshwater locations within each region with which to evaluate patterns in juvenile salmon abundances. Our goal is to operate these projects annually so that we can better understand trends in these populations over time, monitor their health and status of their environment, and build successful forecast models of adult returns.

There are questions and concerns for salmon stocks from these regions, and we have good adult return abundance estimates from ADF&G projects operating in freshwater locations within each region with which to evaluate patterns in juvenile salmon abundances. Our goal is to operate these projects annually so that we can better understand trends in these populations over time, monitor their health and status of their environment, and build successful forecast models of adult returns.

Want to keep track of what we’re up to? Stay updated by following our Facebook page, where we post weekly updates on all things salmon (and sharks!) in the marine environment!

Ben Gray is a fishery biologist for ADF&G based in Anchorage and a team member of the Salmon Ocean Ecology Program.

Subscribe to be notified about new issues

Receive a monthly notice about new issues and articles.