Alaska Fish & Wildlife News

May 2024

A Caribou Heritage

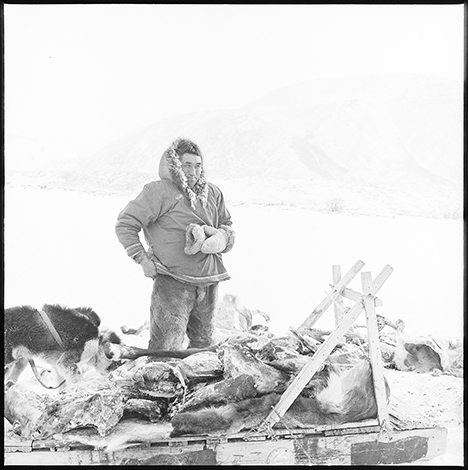

Anaktuvuk Pass Elder Charles “Sollie” Hugo

When the Alaska State Board of Game met in Kotzebue in January of 2024, public testimony focused on caribou. Specifically, proposed harvest limits of the Western Arctic Herd. Caribou are important to the indigenous Iñupiat living in northern Alaska, especially in Anaktuvuk Pass, where most of their protein comes from caribou. Among the many voices that testified, one stood out - Anaktuvuk Pass elder Charles “Sollie” Hugo. He told the board that for many residents of Anaktuvuk Pass, “The grocery store is what comes walking by.”

Sollie’s ancestors observed countless migrations, and understanding migratory patterns is critical knowledge, says Sollie. “You have to know when and from where the caribou will come. We are caribou people not just because we eat them - it’s because we have studied them for thousands of years. From studying their physiology, we learned how to tell which females were without calves. We also learned from other animals living among them, and they learned from us. An age-old question we have is did we learn how to corral caribou from wolves, or did they learn from us?”

Essential Knowledge

As a toddler, Sollie literally cut his teeth on the soft tendons from the front foreleg of caribou. At 6 or 7 years old, he learned what skin to use for drums. At 8, he learned how to keep the pack dogs quiet when the caribou were nearby. When the first caribou arrived, often a female followed by a small group, elders taught him not to disturb the first group because they were blazing trail for the many caribou who would follow. Once caribou had been harvested, he learned what parts needed to be put away quickly, and what could wait. In the spring, a harvested caribou could be brought to the cellars. The soft tips of antlers from caribou harvested in the spring when antlers were still soft were a delicacy to be savored. In the fall, when the weather is still warm, you had to make paniqtaq (dried meat) with the backstrap and ribs at the hunting campsite before the meat spoiled. Later in the fall, when it was cold enough, the caribou meat got placed under stones and boulders. Once the stones were set in place, water was poured over them, and once frozen, this ice encrusted cache would keep even wolverines away from the meat.

Life lessons Sollie took to heart. He learned by listening to elders and watching and following his older brothers. When he harvested his first caribou, he shared it with the elders. Like the overwhelming majority of Anaktuvuk Pass residents, Sollie is Nunamiut, and their way of life has depended upon this intergenerational exchange. Now an elder himself, Sollie works to preserve Nunamiut culture in his role as curator of the Simon Paneak Museum in Anaktuvuk Pass.

The Nunamiut are “people of the land” a group of inland Iñupiat whose main source of food has always been caribou - unlike most other Inupiat who live in coastal areas where marine mammals and fish are a large part of the diet. In addition to food, the caribou provided the Nunamiut with the clothing, shelter, and tools necessary for survival in the Arctic for millennia. Sollie describes caribou, or tuttut, as well-travelled with travel destinations dictated by the season. “Tuttut know when to travel and when not to travel,” he says. The caribou inhabiting the open tundra and mountains of Northern Alaska travel up to four hundred miles between their summer and winter range. Caribou migrate longer distances than any other land mammal on earth and for thousands of years the Nunamiut traveled with them. Knowledge of this migration gathered over thousands of years from all those ancestors who have come before, has been transmitted to successive generations.

Because their survival was inextricably linked to these caribou, the Nunamiut were a nomadic people until the middle of the 20th century, when they settled an area between the sources of the Anaktuvuk and John rivers. When the Nunamiut began establishing a permanent settlement at Anaktuvuk Pass in the late 1940s, it heralded the end of their nomadic lifestyle, but their relationship to and reliance upon caribou remained. Anaktuvuk is an anglicized variation of the Inupiaq “Anaqtuuvak” which loosely translated means “place of many caribou droppings.”

Caribou Heritage

Much of Sollie’s father Clyde Hugo’s early life was nomadic. In the early 1900s when the caribou populations in the Central Brooks Range crashed, his family spent time among the Gwich’in, the northernmost group of Athabascans living to the east of the Nunamiut who hunted the Porcupine Caribou Herd. Sollie’s family also spent time whaling in coastal Inupiat communities before returning to the Anaktuvuk Pass region in 1935. When Sollie was born in 1958 his family was among the last nomadic Nunamiut, but since the age of two he has lived in the permanent settlement of Anaktuvuk Pass an area traversed by the Central Arctic, Teshekpuk Lake, and Western Arctic caribou herds. Sollie remembers when the Porcupine Herd made their way through the mountains in the spring on their way to the calving grounds, but he says since the building of the Haul Road (Dalton Highway built in 1974), they no longer come.

Sollie’s earliest memory is still very vivid. He’s a little boy, probably 3- or 4-years old walking home from a hunting campsite during the fall migration. He says there really are no words to express his people’s connection to caribou. Quantifying the Nunamiut relationship with caribou, “is like trying to define human nature,” he said.” “The medicine man or medicine woman does not separate the person from the land, or the body from the spirit. We learn to dance before learning how to walk. We sing songs to make the caribou arrive.”

Deb Lawton is the Wildlife Education and Outreach specialist for West and Northwest Alaska, based in Kotzebue.

Photos courtesy Anchorage Museum of History and Art, Library and Archives

Subscribe to be notified about new issues

Receive a monthly notice about new issues and articles.