Alaska Fish & Wildlife News

May 2024

Harbor Porpoises Highlighted for Surveys

New tools aid study of secretive marine mammals

In February, Biologist Christi Bubac looked out the window of her office on the Juneau waterfront and saw a pair of harbor porpoises surface near the Juneau-Douglas Bridge. The water flowed like a river in the ebbing tide, and their dark gray backs broke the surface without splashing. Their timing was excellent: Bubac, a marine biologist with the Alaska Department of Fish and Game, is organizing a three-year, region-wide survey of harbor porpoises in Southeast Alaska. She called Seth Bartusek, a certified drone pilot for ADF&G, and Barb Lake, a marine biologist across the hall.

“Seth and Barb went outside and got footage of the pair,” she said, showing me the video. From 250-feet directly above, a fast, graceful porpoise arcs across the frame. The drone camera zooms in and the second porpoise materializes near the first. “This is right out here – look how tiny they are.”

Tiny is relative for a 130-pound animal, but it’s appropriate in the context of marine mammals. Since earning her Ph.D. in Ecology, Bubac has flown aerial surveys in small planes over school-bus-sized North Atlantic right whales off the Carolinas, and conducted shore-based studies of killer whales in Washington’s San Juan Islands. She studied gray seals in Novia Scotia (they can top 800 pounds), and even the loggerhead, green, and leatherback sea turtles she worked with outweigh these harbor porpoises.

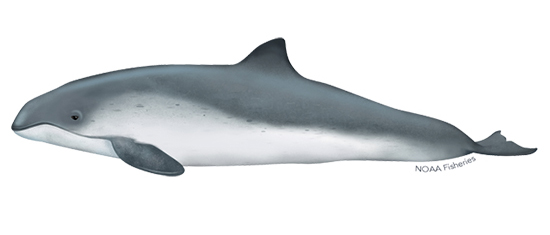

“They’re four to six feet long – that’s the size of me,” she said. “They’re the smallest cetacean in Alaska waters; in fact, the only one in the world that’s smaller is the vaquita, and they’re almost extinct.”

Harbor porpoises are common in Southeast Alaska’s Inside passage, a 400-mile-long network of glacial fjords and densely forested islands along the southeastern panhandle. Relatively little is known about them, and potential threats are raising concern about the animals. Biologists hope to get a better understanding of porpoise numbers, habitat use, and their genetic relatedness. Porpoises in different parts of Southeast may be genetically distinct, as existing data suggests they don’t seem to interbreed, migrate, or move across the region. How they are defined as separate stocks or populations will affect how they are protected and managed.

Prime Habitat for Marine Mammals

Harbor porpoises are federally protected under the Marine Mammal Protection Act (MMPA) managed by NOAA Fisheries. This federal law protects all marine mammal species from significant declines caused by human activities.

Bubac is based in Juneau, home to the largest whale watching fleet in Alaska, and an excellent place to study marine mammals. More than a hundred humpback whales reliably summer in these waters; some are whales identified in pioneering research done here in the ‘70s and ‘80s, others are their offspring and grandchildren. Sea otters, once near extinction, flourish in the region, and Steller sea lions are a common sight. Resident killer whales hunt salmon and other fish in these waters, while transient killer whales hunt marine mammals like harbor porpoises.

Harbor porpoises tend to get overshadowed by the charismatic megafauna referenced above. Their larger porpoise cousins, the Dall’s porpoise - also common in the region and eaten by killer whales - are better known, swimming alongside ships and boats and darting in and out of the wake, breaking the surface with a distinctive “rooster tail” splashing. Pacific white-sided dolphins are also found in these waters, less common but with more conspicuous surface behavior.

Bubac’s colleague, Fish and Wildlife Technician Barb Lake, considers harbor porpoises to be underappreciated. “On whale watching trips, the naturalists don’t even point them out to tourists,” she told me. “They are fast and hard to see, and as soon as you point in their direction, they’re gone.”

They favor near-shore waters, which puts them close to fishing activities. Salmon gillnetting can be a particular hazard. That’s one impetus for the study. A gillnet hangs in the water like a long curtain, and harbor porpoises can become entangled and drown. Studies have shown that gillnet fisheries can pose a risk to harbor porpoises, and previous surveys in Southeast have noted high concentrations of porpoises in areas important to this fishery. NOAA Fisheries has been conducting a study in Auke Recreation Area just north of Juneau the past three years to test pingers: an acoustic alarm system that can be attached to fishing nets. Pingers have been helpful in preventing humpback whales from becoming entangled in gear, and biologists are hopeful a modified version will work for porpoise as well.

Spotting Porpoises

Bubac is working with about eight state biologists, and the porpoise team has been training for the upcoming surveys. Beginning in mid-May, the team will begin surveys using various research platforms including manned and unmanned aircraft as well as vessels.

“We’ve been training their eyes,” Bubac said. “With aerial surveys over water, you’re not looking for animals, you’re looking for a disturbance in the water - something that doesn’t fit. Then your brain puts it together, ‘there’s a whale there!’”

Barb Lake offered a couple examples: “Whales have a large distinctive blow that can hang in the air, and you can see from a distance. Sea birds can be a clue to a whale’s presence as they will be in the air swooping on the ball of fish the whale has corralled to the surface.”

Harbor porpoises are difficult to spot. They are too small to produce a visible blow and are typically feeding on fish at depth. Small waves can hide their small, triangular dorsal fin, and they can travel in unexpected directions underwater until they next surface for air.

Lake said the February afternoon they flew the drone outside the Fish and Game office, she could see porpoises pretty well from shore, but they were much harder to see from above.

“Seth was looking from the drone-view down at the water, and I was directing him, ‘follow that long tide rip towards the bridge, they’re between those two rough patches.’”

They’ve been practicing out the road at Auke Recreation Area, a local harbor porpoise hot spot. Seth Bartusek is one of three on the project licensed by the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) and experienced with flying drones, and he said he’s still learning.

“I fly at 250-feet generally for harbor porpoises,” he said. “I’m still experimenting with what height works best, they’re so small and cryptic it’s easy to miss them on the drone. Sometimes I think I should be flying lower, but I have found that that can limit your field of view and higher is maybe actually better. We got out to Auke Rec twice this week and saw porpoise both days, but one day got totally skunked finding them on the drone. Figured that’s the first of many times they’ll outsmart me.”

The research team is authorized under a NOAA Research Permit to fly drones over harbor porpoise for their work. The noise and close proximity of drones can harass animals and cause stress, so pilots fly as high as possible within FAA regulations, and camera capabilities. NOAA Fisheries is currently developing national guidance for public drone operations near marine mammals. Until then, NOAA Fisheries recommends following the guidelines for viewing wildlife from aircraft and avoid harming or disturbing marine mammals protected by federal law.

The research team is authorized under a NOAA Research Permit to fly drones over harbor porpoise for their work. The noise and close proximity of drones can harass animals and cause stress, so pilots fly as high as possible within FAA regulations, and camera capabilities. NOAA Fisheries is currently developing national guidance for public drone operations near marine mammals. Until then, NOAA Fisheries recommends following the guidelines for viewing wildlife from aircraft and avoid harming or disturbing marine mammals protected by federal law.

In addition to drones, the research team will also do surveys from a fixed wing plane, bringing in some aerial-surveying specialists from Owyhee Air Research. A plane equipped with an infrared (IR) camera and two Fish and Game biologists will accompany the pilot and camera operator on the surveys. Bubac showed me images they photographed of sea otters that blend with the water surface – and pop right out in infrared photos. Infrared photography has potential with marine mammals in cold Alaska waters.

“If the harbor porpoises’ body is not warm enough to be picked up by the IR camera as the animal surfaces with cold water flowing over it, then we’re hoping the blow will be warm enough,” Bubac said. “Infrared sensors will not penetrate the water, so we will be relying on visual cues as animals surface. To our knowledge, this is the first time this has been tried with harbor porpoises, but it has worked well with other marine mammals including sea otters and narwhals. Narwhals are a larger-bodied cetacean, but other researchers have documented the heat signature of fluke prints, which is wild.”

Aerial surveys will continue through the end of June, and will include regular photography as well. The program has invested in some excellent cameras and lenses, and Bubac has been working with the new gear. She’s experienced at aerial surveys: she logged more than 500 hours of in-flight work on North Atlantic right whales, and in the past year in Alaska, she’s completed about 20 in-flight hours conducting Steller sea lion surveys.

“I flew last week,” she said. “We photographed a bunch of haul-outs. It was clear but pretty windy, a six-and-a-half-hour day.”

She showed me tack-sharp aerial photographs she’d taken of large groups of sea lions hauled out on rocky outcrops about 100 miles west of Juneau on the Outer Coast.

“With the right camera equipment, from a thousand feet up in the air it is possible to get a sharp, beautiful picture of a whale that pretty much fills the frame,” she said.

The aerial and boat-based observers will also be opportunistically photographing and documenting sea otters, killer whales, and humpback whales, making the most of the surveys. Photographs of humpback whales, showing the tail flukes or dorsal fins enable whale researchers to identify specific individuals.

The Stranding Network collects reports of stranded, injured, entangled, or dead marine mammals anywhere in the state. They can be reached on their 24/7 hotline: 877-952-7773 (save the number in your phone so you have it when you need it).

Fluke Prints and eDNA

In early June, the team will begin pilot surveys from a 70-foot liveaboard vessel as well as from a skiff with an observation platform to test differences of platform in porpoise detection rates. A protocol has been established involving line and strip-based transects, and the skiff will occasionally divert when there’s an opportunity to target porpoises to gather genetic material.

“We’ll be sampling the water for harbor porpoise environmental DNA,” Bubac said. Water samples are taken from fluke prints, “tracks” left on the surface of the ocean when a marine mammal surfaces to breathe. These tracks can be fairly distinct.

“You can often see the actual disturbance,” she said. “It looks like a circle, it might be a patch of smooth water or a ring of ripples. It has to be fairly calm to do any monitoring anyway. The moment you get whitecaps it gets really difficult to detect porpoise at the surface.”

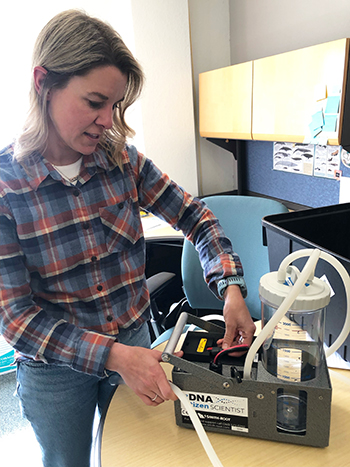

She showed me the eDNA collection device - a plastic flask with tubing and a small pump, culminating in a specialized funnel containing a silver-dollar-size disc of filter paper – collectively referred to as a self-preserving filter pack. The biologist scoops up water from the fluke print and the water is subsequently pumped through the filter. The disc of filter paper is dried and completely self-preserved until later processing. That water might contain just a few cells shed by the passing porpoise, but that’s enough.

“We will send the filters to a lab and they will isolate the DNA as if it was from a piece of tissue,” she said.

Environmental DNA may be used to identify an individual animal and to assess the relatedness between animals – for instance, if members of a group are more closely related than expected. Animals within a region can be identified by their genetic profile, and some evidence exists that indicates harbor porpoises from southern Southeast Alaska are genetically differentiated from porpoises in the northern area. These stocks are also referred to as demographically independent populations.

A decade ago, nine stocks of harbor porpoises were recognized on the West Coast, including three in Alaska waters: the Southeast Alaska stock, the Gulf of Alaska stock, and the Bering sea stock. In 2023, the once single Southeast Alaska stock was split into three additional stocks – a decision made following findings of fluctuating porpoise numbers, distribution patterns, and genetic differences between northern and southern Southeast Alaska inland waters and offshore regions. The upcoming surveys by ADF&G will build upon this research to provide contemporary population size estimates and thorough genetic sampling coverage.

All this matters, because management actions are directed at specific populations that may have implications on fisheries. The water Bubac and her colleagues scoop from fluke prints should provide important insights in combination with aerial and vessel-based abundance surveys.

Links

https://www.fisheries.noaa.gov/topic/marine-life-viewing-guidelines

Harbor porpoise species profile

Permit for the harbor porpoise study including drones, aerial surveys, and vessel surveys is: NMFS APPS No. 27993. The permit for photographing entangled or stranded marine mammals is NMFS Permit No. 24359

Subscribe to be notified about new issues

Receive a monthly notice about new issues and articles.