Alaska Fish & Wildlife News

May 2024

Ask a Wildlife Biologist: May is for Migration

Q) What Alaskan animal migrates the farthest?

Q) What Alaskan animal migrates the farthest?

Question from 8th grade students at Birchtree Charter School - Matanuska-Susitna Borough School District

A) To start - what is migration, anyway? A simple explanation: migration is animals moving between different habitats, usually in a seasonal cycle. Animals generally migrate to find food, breed, give birth, raise young, or escape predators and/or unfavorable conditions. Alaska is unique in that it hosts animals that make some of the longest airborne, oceanic, and overland migrations in the world. While there is a clear winner for “farthest” migrator, many other species deserve consideration for the most interesting, the most difficult, or the longest migration per mode of travel.

Longest overall and flight migration: Arctic terns (Sterna paradisaea)

Arctic terns fly from the North to the South Pole region and back every year, which is the longest migration of any animal on Earth. On average it is something like 25,000 miles round trip, but the longest recorded track for a single tern within a single year was 59,650, which is twice the distance around the Earth! Arctic terns eat small fish and insects from and around water bodies they encounter while migrating, breeding, and summering. They weigh around 100 grams (think a single banana), and can take advantage of oceanic winds to cover more distance efficiently.

Arctic terns fly from the North to the South Pole region and back every year, which is the longest migration of any animal on Earth. On average it is something like 25,000 miles round trip, but the longest recorded track for a single tern within a single year was 59,650, which is twice the distance around the Earth! Arctic terns eat small fish and insects from and around water bodies they encounter while migrating, breeding, and summering. They weigh around 100 grams (think a single banana), and can take advantage of oceanic winds to cover more distance efficiently.

Longest land migration: Caribou (Rangifer tarandus), especially Porcupine caribou herd

Caribou have the longest known terrestrial (or land-based) migrations on the planet. Caribou in large Arctic herds can walk more than 2,000 miles each year, a distance that often adds up to walking the distance of the diameter of the earth within their lifetimes. Caribou migrate to find optimal forage, to reduce exposure to insects in the summer, to avoid predators, and females migrate specifically to give birth to calves on calving grounds in the early summer, especially in larger herds. Biologists have recorded the longest migration tracks (using GPS collars to follow animals in the herd over time) for caribou in the Porcupine herd of Northeastern Alaska and Northwestern Canada.

can walk more than 2,000 miles each year, a distance that often adds up to walking the distance of the diameter of the earth within their lifetimes. Caribou migrate to find optimal forage, to reduce exposure to insects in the summer, to avoid predators, and females migrate specifically to give birth to calves on calving grounds in the early summer, especially in larger herds. Biologists have recorded the longest migration tracks (using GPS collars to follow animals in the herd over time) for caribou in the Porcupine herd of Northeastern Alaska and Northwestern Canada.

Longest oceanic migration: Gray whale (Eschrichtius robustus)

The Eastern Pacific stock of gray whales migrates from the lagoons of Baja California, Mexico all the way into the Arctic waters of the Bering and Chukchi Seas. This swim is 5,000 to 7,000 miles each way - 10,000 to 14,000 miles round trip. Gray whales calve in the warm waters of Baja in winter (December to April). They then migrate to feed in the nutrient-dense North Pacific, Bering, and Chukchi Seas around Alaska in the summer (May to October) before returning south. They feed in northern waters and grow fat reserves to last them through both directions of their migratory loop and the calving season – which means they eat rarely or not at all for at least half of the year. Gray whales are the only species of baleen whales that feed by scraping relatively shallow muddy and sandy ocean bottoms and filtering the sediments using their baleen to feed on crustaceans.

Longest freshwater migration: Chinook salmon (Oncorynchus tshawytscha)

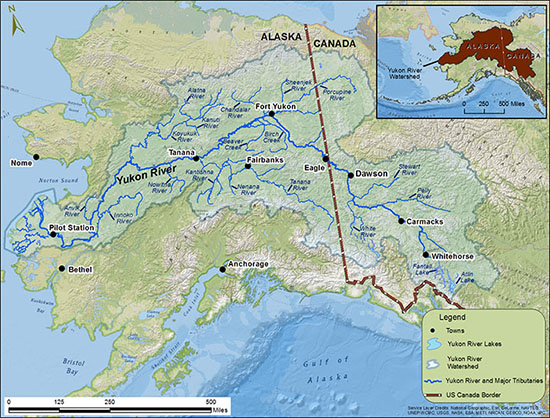

There are five species of Pacific salmon, the largest of which is the Chinook or king salmon. King salmon are anadromous, living both in fresh and saltwater for different parts of their lives. Mature adults swim upstream to lay eggs, the eggs hatch into juvenile fish that make their way back to the ocean in 1 to 2 years, mature into adults in the ocean in 3 to 5 years, then return to their natal stream or river to spawn and eventually die. The distance king salmon migrate varies depending on the tributary they spawn in, but king salmon that swim the full distance of the Yukon River (all the way across Alaska into the Yukon) can swim over 2,000 miles in one direction. This is the longest known freshwater migration in Alaska.

The Yukon River and its enormous watershed in Alaska and Canada. Chum salmon also migrate up the Yukon, and coho salmon migrate more than 1,000 miles up the Yukon and up the Delta Clearwater River south of Fairbanks (Near the center of the map).

Other migrations that are worth considering

There are many animal migrations to and from, within or near the state of Alaska that are remarkable, even if they aren’t the farthest or longest. Many deserve honorable mentions.

Numerous examples of the most impressive migrations are avian - more than 250 bird species migrate to and from Alaska each year to take advantage of the short and productive summers.

The longest recorded continuous flight thus far belongs to a four-month-old bar-tailed godwit (source: USGS juvenile bar-tailed godwit flight) that flew non-stop from the Kuskokwim Delta to Tasmania, Australia in 11 days. This was 8,425 miles in total…without stopping at all!...which is somewhere around 750 miles a day. Many migrating shorebirds are unable to land and swim well in water, and thus must complete continuous flights to reach their migration destinations.

The longest recorded continuous flight thus far belongs to a four-month-old bar-tailed godwit (source: USGS juvenile bar-tailed godwit flight) that flew non-stop from the Kuskokwim Delta to Tasmania, Australia in 11 days. This was 8,425 miles in total…without stopping at all!...which is somewhere around 750 miles a day. Many migrating shorebirds are unable to land and swim well in water, and thus must complete continuous flights to reach their migration destinations.

Sandhill cranes (Grus canadensis) can fly up to 35 miles per hour and cover 300 to 500 miles per day (with a good tail wind), with a one-way migration distance often over 5,000 miles. These cranes are among the largest winged migrants and often fly more than two miles off the ground (regularly up to 13,000 ft.) by taking advantage of the lift created by thermals, or rising columns of air coming off the ground warming from the sun. They also might be among the most recognizable symbols of migratory seasons in Alaska, along with swans, geese, and duck species that arrive in spring.

Olive-sided flycatchers have one of the longest migrations of any North American songbird at 6,000 to 7,000 miles each way between Alaska and South America. Olive-sided flycatchers have also declined 78% over the past 40 years, and mortality during migration is especially detrimental, as this species also has one of the lowest reproductive rates among songbirds. Long migrations take a lot of energy and resources, and migrating species can be vulnerable to environmental conditions along the entirety of their migratory routes. In addition to shedding light on the migratory route of individuals and species, studies that track animal migrations are one of the best ways to identify the biggest challenges facing threatened species, and to propose management solutions for recovery.

The smallest migrators are some of the mightiest. Too small for GPS tags, and a tenth of the weight of a  flycatcher, the 3 to 4 gram (think a single penny) rufous hummingbird is the most widely spread hummingbird species in North America. Rufous hummingbirds generally winter in Mexico and maybe even into South America, and yet have the northernmost breeding range of any hummingbirds in the world. A male hummingbird banded in Florida was caught six months later in Alaska, 3,530 miles away!

flycatcher, the 3 to 4 gram (think a single penny) rufous hummingbird is the most widely spread hummingbird species in North America. Rufous hummingbirds generally winter in Mexico and maybe even into South America, and yet have the northernmost breeding range of any hummingbirds in the world. A male hummingbird banded in Florida was caught six months later in Alaska, 3,530 miles away!

However, birds are not the only impressive migrators. Many fish, marine mammals, and terrestrial mammals deserve mention. Sheefish, large whitefish that can weigh up to 60 pounds, have the second longest freshwater migrations in Alaska, traveling up to 1,000 miles in northern and interior Alaska rivers to lay as many as 400,000 eggs.

Humpback whales travel thousands of miles from the sub-tropics to the Gulf of Alaska, Bering, and Chukchi Seas, and back. Populations of walrus, bowhead whales, and beluga whales migrate seasonally with the growing and receding sea ice pack, which despite being more localized to northern waters, requires swimming several thousands of miles each year.

Elevational migrations: Sitka black-tail deer, Dall sheep, and mountain goats migrate seasonally by ascending and descending in vertical elevation with the growing and receding snowpack, food availability, and movement of predators.

Alaska is home to species with a diversity of migratory patterns, routes, and behaviors. These are only a few of the many migratory stories in the state. Find many species’ profiles on our website, articles from the AFWN archives about the species mentioned, and an issue of our K-12 student magazine, Alaska’s Wild Wonders: Mighty Migrators, for more information and lots of fascinating details. Thanks for the question!

Jen Curl is the statewide Teacher Resource and Youth Education Specialist for the ADF&G Wildlife Outreach and Education program, and works out of the Fairbanks office.

Longest recorded track for a single tern within a single year (2016) Newcastle University study tracks longest ARTE migration

A Tern of EventsAlaska's Stately Sandhill Cranes

Long-distance hummingbird sheds light on migration

Alaska’s Wild Wonders: Mighty Migrators

Subscribe to be notified about new issues

Receive a monthly notice about new issues and articles.