Alaska Fish & Wildlife News

May 2023

Golden-crowned Sparrow

More to this songbird than meets the eye

Alaska springtime is marked by many signs, but my favorite is picking out the melodies of different songbirds. Their music is a welcome harbinger of new growth and renewal, marking that transition from dark days into longer and lighter ones. Springtime arrivals take many forms; there is the emergence of queen bumblebees as they seek out suitable nest sites, awakening bears, and arrival of Golden-crowned Sparrows.

The Blueberry Knoll Trail in the Government Peak Recreation Area in Palmer became one of my favorite lunchtime hikes. I was witness to all of its seasons, and was grateful that the well-kept trail allowed passage whatever time of year (being mindful, of course, not to hike while it was muddy). Last spring, I was listening to birdsongs, picking out melodies among the cascading calls when I caught sight of a butter-yellow flash amidst the low, squat shrubs below the trail. I did a double-take; sparrows generally wear browns and greys, and this sighting was a new one.

I’m glad I stopped to take a closer look. This particularly glorious springtime visitor wore the familiar brown-and-grey of Alaskan song sparrows, but with a strip of brilliance on the top of his head. The sunflower-yellow was bordered by two streaks of black, bringing to mind bees, as anything black and yellow often does with me. Like other sparrow species, they weigh no more than 35 grams (1.25 oz), a bit more than a one-quarter stick of butter, and measuring 15-18 cm (6-7 inches) in length.

This newcomer had not been part of the winter crew, which consisted mostly of chickadees and dark-eyed juncos braving the cold. Zonotrichia atricapilla, the rotund Golden-crowned Sparrow, may appear to materialize overnight. This is because they favor migration at night, so their movements aren’t seen by day. Their song is distinctive and opens with a three-note minor key descending melody; miners in the Yukon likened the call to phrases such as, “no gold here,” or “oh, dear me,” or “I’m so tired,” followed by “tee tee tee,” and other trills and whistles. A study published in The Auk, the journal of the American Ornithological Society, documented these sparrows as having different dialects across their geographic range.

Most of the classic work on song learning was done with Golden-crowned Sparrows close cousins, White-crowned Sparrows, which also have different dialects. Researchers found with both species, the longer the migration, the greater the variable dialect between birds, with birds singing various strings of trills, whistles, and phrases, but generally with the same introductory whistle. Ninety percent of the birds in the study shared one song in common – a descending whistle, flat whistles, and a trill. And much like many of us who might mistake lyrics the first time we hear a song, and discover years later that we had it wrong – birds that acoustically erred in their learning continued belting out the wrong melody if there weren’t others to correct them. The fifteen-year study also found that songs were sung consistently through generations, so once a song is learned, it more or less stays that way. Research on White-crowned sparrows indicates that a young sparrow learns songs in the neighborhood of its nest. These songs are learned in stages. Because these sparrows return to the same nesting grounds, these unique dialects are lasting.

There is a great deal of evidence as to why birds sing in the summer, but as to why they sing in the winter, there aren’t any answers that offer certainty on the subject. Male birds typically sing to attract a mate during breeding season when defending territory in the summer. Golden-crowned sparrows, however, sing throughout the winter, and that’s both males and females. They may be drawing territorial lines, or signaling food sources to other sparrows in an act of cohesion and community. Other theories have pointed to singing as a greeting or bonding ritual for familiar sparrows.

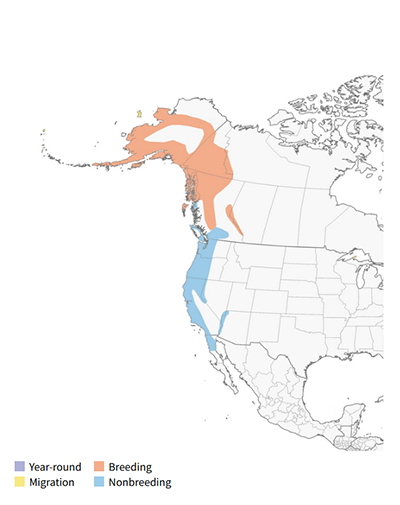

The quintessential snowbird, they spend more time in their southern habitats over the winter, and return to their northern breeding grounds in the spring and summer. Wintering grounds stretch from southern British Columbia to northern Baja, California. Summers are spent in Alaska and northwestern Canada. A friend of mine, a former Denali Park Ranger Interpreter, confirmed sightings in the National Park. They favor short conifers, alders, and willows for habitat when further north, and in the south, shrubby brush, often near rivers.

My first sighting of this lemon-tufted bird was in the shrubs, and so it seems right that they breed in shrubby tundra near the coast. To crown it all, they often return to the same nesting grounds as the year before, even within a 100-foot radius (which also reinforces the persistence of those song dialects).Their nests are often concealed on the ground, under shrubs, with males signaling territory from up high– so it is well worth being mindful of their singing. In Alaska, watch for them near alder, willow, and evergreen habitats, particularly dwarf willow, and often in the company of White-crowned sparrows or Dark-eyed Juncos.

Golden-crowned sparrows, interestingly, exhibit distinctly different social behaviors in the summertime, when they breed, and the wintertime, when they migrate south.

Given that the summertime is also the breeding season, it stands to reason that they are extremely territorial. They band together in pairs, and while generally monogamous, female Golden-crowned sparrows will mate with other partners. Males will often sing to defend territory, as much as 2.5 acres of land, while females collect nesting materials. They are less aggressive while foraging, given the abundance of food.

Their behavior is starkly different in the wintertime. Their time in the north is defined by squabbles and the drawing of territorial lines; when they move south they grow more neighborly. There is evidence of Golden-crowned Sparrows having a different, complex social structure in the winter, flocking with familiar birds of the same species. This “tethering” behavior is not dependent on kinship; these bonded birds are entirely unrelated to one another. They bond, forage, and alert one another to threats. These incredible winter relationships last a lifetime, but are absent during migration and when they return to their summer breeding grounds, resuming upon arriving in their wintering areas.

These birds also distinguish each other’s status and fighting ability through their most distinguished feature: their brightly colored heads. Researchers with the UC of Santa Cruz discovered that Golden-crowned sparrows could gauge each other’s fighting ability by their black-and-yellow stripes alone. Yes, as with professional wrestling, much is conveyed by the vibrancy of their masks. Brighter hues were more consistent with the better fighters, while birds with duller tones were less dominant. A 2018 study further showed that, among fellow neighbors – tethered birds – whether it was mustard yellow or lemon yellow, the tones didn’t determine the pecking order. Yellow plumage was a signal of social status only when worn by strangers.

The yellow stripe serves as “badges of status”, determining dominance without expending energy (or risk of injury) on physically fighting. Melanin – darker pigments – can be generated by amino acids in the body, while the brightness of the yellow coloration is directly related to carotenoids in their diet. Carotenoids are responsible for the hue of vegetables such as carrots and sweet potatoes, so it stands to reason that the intake correlates with the health of the bird. The brighter the color, the better-fed and nourished the bird, making for a more robust opponent. Biologists refer to this as an “honest signal” because it is reliably associated with the bird most likely to win a fight.

Researchers even painted bold colors onto birds, and found that it fooled birds that were unfamiliar with each other. Birds that banded together in the same community were more likely to chase away sparrows with duller shades on their crowns. These communal bonds improve chances of survival, with birds spending less time on aggression and more time on foraging. Not altogether different from us; we readily band together with our friends and may distrust individuals we don’t know well.

Golden-crowned sparrows mostly feed on seeds and insects. Winter diet consists of seeds from weeds and grasses, fruits like apple, grape, elderberry, grains like oat and barley, buds, flowers, and plant sprouts. Less is known regarding their summer diets, but is likely similar and includes spiders. They are known to eat wasps, bees, moths, butterflies, beetles, crane flies, and termites.

It’s safe to say that the outside world harbors thousands of small wonders. Birdsong that becomes as familiar as our alarm clocks, or the early light of Alaskan summers, may become part of a wider, textured sound we associate with the morning. Amidst that sound are a thousand stories, but each story offers incredible insights into the ecosystem that surrounds us. With Golden-crowned sparrows, this is no exception.

Subscribe to be notified about new issues

Receive a monthly notice about new issues and articles.