Alaska Fish & Wildlife News

November 2022

Become a Skull Detective

Finding animal bones, especially skulls, can be exciting! And everyone loves a good mystery. There are many fascinating things you can learn from animal skulls. Skull characteristics offer clues about animal diets and helps to classify animals into related groups.

Notice the mystery skull. Do you know what animal it is? To make solving this mystery a bit simpler we will focus on mammals only, though some of these concepts apply to other groups of animals as well.

What can we learn from this skull, even if we have no idea what animal it is? Here are a few key questions to ask: Where are the eye sockets (orbits) located? What do the teeth look like – are they all sharp or mostly flat? Does the jaw have a large space with no teeth? How long is the snout? Is the joint of the jaw loose or tight?

Teeth as tools

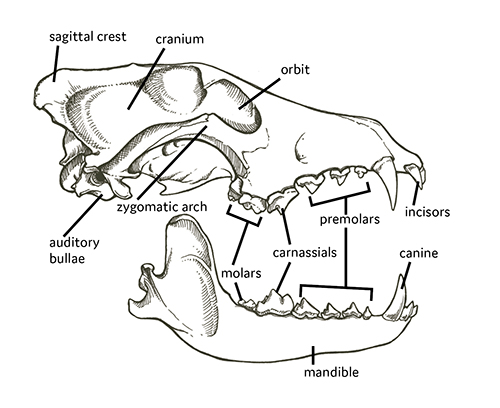

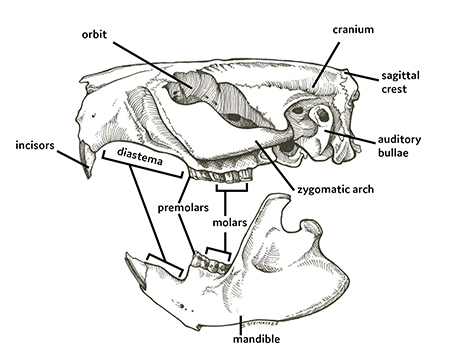

Teeth are among the features on a skull that we notice first. What can teeth tell us? It helps to think of teeth as essential tools that animals need to survive. The arrangement of teeth in the skull is called dentition, and it provides a lot of information about the animal that the teeth belong to. The shape and structure of the jaws are another clue.

Teeth and jaws can help decipher whether a mammal is a carnivore, herbivore, or omnivore. Carnivores, or meat-eaters, rely on canines, carnassial teeth, tight jaws that move up and down (and not side to side) to catch prey and consume meat. Carnassial teeth are specialized premolars or molars that are meant for tearing or shearing. Tight jaws and prominent canines help carnivores pierce and hold prey. Alaska has many notorious carnivores - lynx, wolves, fox, wolverine, weasels, and many marine mammals, to name a few.

In contrast, herbivores eat plants, and use incisors to cut vegetation. Their canines are either less noticeable than in carnivores or non-existent. There is a space between herbivore incisors and cheek teeth (premolars and molars) called a diastema, where vegetation can be held or carried. Premolars and molars are flatter and made for grinding. Their jaws are also strong, but the jaw joint is often higher than the cheek teeth, and the jaws are loose, allowing side to side movement to chew and grind food. Examples of mammalian herbivores in Alaska include rodents, hares, pika, and ungulates (e.g., bison, moose, goats).

Omnivores have both kinds of teeth – they have prominent incisors for biting and cutting, relatively long and sharp canines for piercing prey, and flatter molars for grinding vegetation. Omnivores generally have a tighter jaw joint that doesn’t allow much movement side to side, so their jaws are often more like carnivores than herbivores. Some omnivores have carnassial teeth (coyotes) while others have more cheek teeth made for grinding (bears). Humans are omnivores – what do you think the shape of your cheek teeth can tell us about human diets?

Returning to our mystery skull. Is it a carnivore, herbivore, or omnivore. Why?

It is all in the eyes

The placement and size of the orbits, or eye sockets provides important hints about the animal in question. Are the eye sockets on the side of the head, like caribou and other ungulates? Or are both in front, like a wolverine? Prey species rely on being able to detect the movement of predators to survive. Eyes are on the side of the head, and each eye can generally see close to 180 degrees peripherally around them, meaning prey species can fully monitor their surroundings.

Eyes in the front allow predators to have binocular vision, which means both eyes face the same direction and perceive a three-dimensional image of their surroundings. Binocular vision allows excellent depth perception for spotting and capturing prey.

If a mammal has particularly large orbits, it may indicate large eyes. What animals can you think of that need particularly large eyes? Perhaps animals that need to see in the dark – either at night or in dark or murky water - flying squirrels, cats, and seals/sea lions to name a few.

Orbits positioned high on the skull may indicate that the species spend time in aquatic environments, where their eyes can remain above water while most of their head/body is submerged. A beaver below is an example (skull overlay illustration by Sarah DeGennaro).

Where are the orbits on our mystery skull? Is it predator or prey?

Which mammals smell well?

The size of the snout and nasal passage, which houses the fragile turbinal bones that provide the structure for the olfactory (smelling) membranes, relates to how much a mammal relies on their sense of smell. The ursid and canid families (bears, wolves, coyotes, foxes, and dogs) are known for their smelling abilities, and have long snouts that allow more surface area for the membranes. You can see the network of fine turbinal bones inside this bear skull.

In comparison, the felid family (lynx, cougars) have much shorter nasal passages, and as mentioned above, large orbits – which might be a clue that cats rely more on good vision than their sense of smell. Compare the snout of the fox to the lynx.

Do you think our mystery mammal has a long, medium, or short snout?

Heightened hearing

Generally, it’s not really possible to identify a skull from the bones of the skull involved with hearing - but it can be a clue. The bones encasing the middle ear are called the auditory bullae. They are a pair of bumps - hollow chambers at the back and bottom of the skull, on either side of the big hole where the spinal cord enters the skull. If an animal has inflated or noticeably large auditory bullae, it is a good indication that the animal has a good sense of hearing. Hares have large auditory bullae, which are circled in the photo below – why would hares need to be sensitive to sound?

Classifying animals using skull characteristics

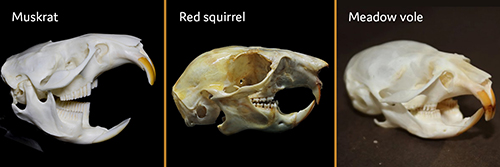

Prior to the modern age of using genetics to classify animals, scientists used physical characteristics to lump animals into related groups. Skulls played a big role in the classification of mammals. Many groups of mammals have skull characteristics shared across species within families, or even orders. For example, rodents comprise an order made of multiple families – squirrels, beavers, and mice/voles among them. All rodents share a distinct group of skull characteristics that help identify that they are rodents. A few of these characteristics include: rodents have no canines; most have large incisors with hardened, orange, enamel on the front; they have a large diastema, or space between their incisors and cheek teeth; and they have flat molars and similarly shaped lower mandibles that help them chew and grind their food.

If you haven’t yet solved our skull mystery – do you think it is in the rodent family? Why or why not?

Skull mystery - SOLVED

What is our mystery animal? We know that it has a diastema and flat teeth – so it is an herbivore. We know that the orbits are on the side of the head, meaning that it is a prey species. Our final hint is that our mystery animal has large auditory bullae. It’s not always possible to figure out exactly what species a skull you find in the wild is from these clues alone, but it does give you a lot more information to start piecing together the diet, habitat, and abilities of the animal in question.

Our mystery animal is a snowshoe hare (Lepus americanus) – did you notice the lack of enamel on the incisors? That was a hint that our mystery animal is not a rodent. Interestingly, hares and rodents share many of the same skull characteristics, but hares are in the order called Lagomorpha. Lagomorphs include hares, rabbits, and pika. Another obvious difference between rodents and lagomorph skulls is that lagomorphs have two sets of upper incisors! There is a smaller pair of incisors located behind the larger incisors. These are called peg teeth because they are shaped like a peg and not sharp like regular incisors. Look close, they are small but they are present.

We can learn a lot about animals from studying their skulls. ADF&G has some great resources for educators (or anyone!) interested in learning more about skulls and becoming skull detectives with students or kids. Also, please reference our previous article about if and when you can keep bones, antlers, and animal parts you find in the wild.

Alaska’s Wild Wonders – Skull Detective

Check out a skull education kit

If you are serious about learning more about skulls, you should consider this extensive skull guide:

Animal Skulls, A Guide to North American Species by Mark Elbroch.

Jen Curl and Mike Taras work for ADF&G in Fairbanks as part of the Wildlife Education and Outreach program, within the Division of Wildlife Conservation.

Subscribe to be notified about new issues

Receive a monthly notice about new issues and articles.