Alaska Fish & Wildlife News

February 2022

Tracking Flycatchers

An Epic Journey Powered by Bugs

In my two months of birdwatching in wetlands around Anchorage last summer, I never actually saw one of Alaska’s most unassuming songbirds, the Olive-sided Flycatcher. Their gray and olive plumage camouflages them well in their evergreen environment and I found myself scanning the scraggly treetops in vain for the little perching bird. That isn’t to say they weren’t there, though; I heard their trademark call of “Quick! Three beers!” quite often and quite clearly, considering it can carry from nearly six football fields away.

While many Olive-sided Flycatchers nest in Alaska, their range extends across two continents, from boreal Alaska to Bolivia. Yet their recognizable call has been fading worldwide, with a steep population decline of 78 percent since the 1970s. The species is considered “Near Threatened” globally and a “Species of Greatest Conservation Need” in Alaska. Each year birds return to breed in boreal Alaska and Canada, and down both the east and west coasts of North America. Then, during the fall, they migrate south through Mexico and central America to spend winter months in South America, where they set up winter territories in mountain and riparian (riverside) habitat in places like Ecuador, the Andes, and western Brazil.

Staving the loss of migratory songbirds like the Olive-sided Flycatcher is becoming increasingly urgent. North America has lost one in four birds since 1970, which totals nearly 3 billion breeding adult birds across all ecosystems, with boreal forests experiencing some of the most dramatic losses. Bird species in general play ubiquitous roles across natural habitats, controlling insect populations, acting as pollinators, and dispersing seeds, to name just a few. In addition to being central to every food web and ecosystem, birds also improve quality of life for many people through birdwatching, bird feeders, birdsong, and the presence of their intact habitat.

Where to start?

Conserving and managing North America’s migratory birds starts with identifying the threats and the drivers of the decline for each species. What then is causing the Olive-sided Flycatcher’s decline? Is it their insect food source? Their nesting habitat in Alaska? Perhaps an issue on the wintering grounds? Or something during migration? And how is it possible to best track and quantify this information across trans-hemispherical boundaries?

These were just the sorts of questions that Julie Hagelin and her team at the Threatened, Endangered, and Diversity Program of ADF&G wanted to answer, in an effort to keep Alaska’s species intact and off the endangered list.

Out in the Wetlands

To tackle these big questions, Hagelin’s team needed to start by capturing Olive-sided Flycatchers on their breeding grounds in Alaska. This was easier said than done, as these birds are annoyingly smart, good at evading capture, and tend to be elusive inhabitants of buggy bottomlands, which may explain why not much is known about them. But, thankfully, pioneering research in the 1990’s by another ADF&G biologist, John Wright, had helped determine some basic biological information for Alaska, including when breeding flycatchers are most likely to call during summer. Wright’s preliminary work proved to be a reliable method for efficiently surveying areas to detect study animals—a task that would have otherwise taken long hours with many unknowns. The team even experimented with decoys made on 3D printers to entice birds closer to nets.

The hard work paid off. Hagelin’s team captured almost 100 birds and deployed tiny tracking devices, called geolocators, on their backs. These remarkably lightweight devices (which weigh about as much as a dollar bill) stayed on each small songbird throughout its annual journey to South America and back. Geolocators are a game-changing technology for documenting songbird migration. Unlike satellite-based Global Positioning Systems (GPS), which require heavy batteries to talk to satellites and relay an exact point, geolocators collect data on the intensity of sunlight, which requires very little battery weight. Combined with an on-board clock, light-level data can roughly indicate a bird’s location.

It turns out that many birds, including flycatchers, may suffer their greatest losses during migration, so finding important locations that birds use while migrating is a critical first-step in managing a declining species. Over the course of a year, the team gathered information on where the flycatchers spent most of their time on their migration, what commonly used places were most important for birds to rest and refuel, what routes birds favored, and generally looked to answer where exactly the flycatchers spent the other two thirds of the year when they were not in Alaska.

Doing well in Alaska

During summer captures for the geolocator study, the team also measured the nesting success of breeding flycatchers as well insect prey abundance near nests. What they found was encouraging. Olive-sided Flycatchers seemed to do very well in Alaska, even better than populations in other parts of the breeding range, in fact. About 75-90 percent of Olive-sided Flycatcher nests in Alaska successfully reared chicks each year, compared to reports of 50 percent or less in other breeding locations, such as the Pacific Northwest.

Julie Hagelin detailed why places outside of Alaska, during the flycatcher’s non-breeding period, is a prime suspect of their steep decline. “Our multiple years of field data suggest that birds do quite well on the breeding grounds in Alaska,” she said, “provided they can make it all the way back! Here in Alaska they have broad expanses of intact breeding habitat, and they time their chick-rearing to coincide with the peak of the summer insect pulse. The danger to Olive-sided Flycatcher populations in Alaska, may actually be more about birds suffering high levels of mortality during migration and wintering, and less about successful reproduction.”

Retrieving the geolocators from the birds also proved another challenge, as the bird needed to be re-captured, in order to access the data, and the flycatchers were smart enough to often evade capture a second time. In due course, though, a number of geolocators were recovered and the migratory route of the Olive-sided Flycatchers in boreal Alaska, the first for any population in North America, was finally revealed.

The Journey South

Astonishingly, the little gray birds with barely a 12-inch wingspan were found to fly 14,000-16,000 miles annually down to wintering areas in Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, and Bolivia and back again. They were undertaking one of the longest songbird migrations in North America, an epic journey powered solely by bugs!

Analyzing the migration data also involved the real challenge of how to objectively identify areas “important” to birds. It turns out this involved developing a new method for data analysis. Hagelin’s team collaborated with Dr. Mike Hallworth, a bird migration expert at the Vermont Center for Ecostudies. Dr. Hallworth helped develop, “a new way of analyzing geolocator data, which is also applicable to any type of tracking data for any animal,” said Hagelin.

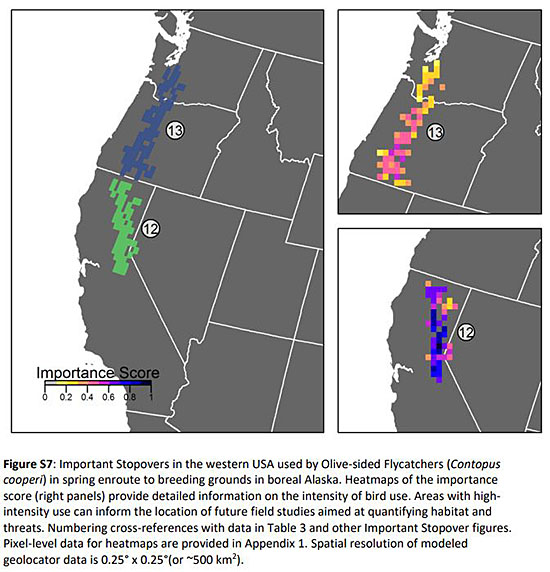

She detailed how they overlaid the tracks of each bird (which indicated the number of birds using an area) and combined this with their length of stay (which likely reflects the amount of resting, feeding). The combined score quantifies intensity of bird use throughout the migratory pathway. This allowed the researchers to generate a “heatmap” of bird use across North and South America, throughout their migratory period. The process specifically revealed 13 “hotspots,” where above-average numbers of birds spent above-average periods of time during migration, sometimes spending over 30 consecutive days. These 13 sites are therefore the most “Important Stopover” regions for boreal-breeding Olive-sided Flycatchers, where individuals spend a preponderance of time of time resting and refueling during their amazing migration across the Americas.

What Next to Reduce Decline?

Important migratory stopover sites are valuable for conservation and management of at-risk species, because they enable managers to target their actions and limited resources at key “pinch points” scattered over vast areas, where birds appear to be most vulnerable. Specific habitats at important stopover locations can be evaluated to understand which resources are critical to Olive-sided Flycatchers, and reveal where trouble may be lurking, in terms of immediate threats to the bird’s survival. For example: Where do the largest populations of flycatchers occur and when? What habitats or natural resources do they rely upon the most? Do any other declining species also use the same stopover areas in large numbers? How can we sustainably manage or maximize resources where birds need them most, thereby reducing threats that may contribute to their decline? Finally, important stopovers provide targeted, management opportunities. For example, if land conversion is occurring in an area, how can we work to retain key habitat features, such as perches of standing dead trees, that birds typically use for feeding?

These are all questions and opportunities for the future. For now, identifying key sites of high-intensity Olive-sided Flycatcher use has been the most important and exhaustive first step in conservation, an incredible accomplishment almost a decade in the making. The paper “Revealing migratory path, important stopovers and non-breeding areas of a boreal songbird in steep decline” has just been published in the journal of Animal Migration as an invited paper, along with many other scientific studies of “extreme migrants” that come and go from boreal and Arctic regions. This research not only addresses future needs for flycatchers and provides a new analysis method for tracking data, it also contains tips for other field researchers wishing to work on this species, including guidelines for how to locate, capture and recover the tags.

Hagelin wryly recalls the buggy wetlands and how difficult the flycatchers were to work with, but that, “people can learn from our collective experience now and have an easier time of it.” This paper is a treasure trove of new collective knowledge, considers other declining long-distance migrants and suggests future work for the conservation and management of North American birdlife and ecosystems.

When I am tromping through the Alaska wetlands again this summer and hear the trademark “Quick! Three beers!” call of the Olive-sided Flycatcher, I feel that I can better appreciate how this tiny bird has flown from Fairbanks, Alaska down the coast of the entire continent and perhaps into Peru. Spending more than half its life in both mountainous and tropical regions, before moving back up through the boreal forests of the Pacific Northwest and into the scraggly wetland forests of the sub-arctic tundra to raise another generation of adventurous, hemisphere-hopping songbirds.

Arin Underwood is a wildlife biologist with ADF&G’s Threatened, Endangered, and Diversity Program. She works with citizen science projects and supports research on birds and small mammals in Southcentral Alaska.

Find more information on the Olive-sided Flycatcher project on the TED website. To support wildlife research and education in Alaska, purchase the brand new 2022 conservation stamp featuring one of Alaska’s rarest songbirds, the Bluethroat.

Follow the TED Program on Facebook and Instagram for updates on current non-game species research.

Subscribe to be notified about new issues

Receive a monthly notice about new issues and articles.