Alaska Fish & Wildlife News

September 2021

Muskox Research in Alaska

Muskox shared the open tundra of ice-age Alaska with mammoths and mastodons, steppe bison and caribou. Herds of stocky, shaggy muskox faced off Beringian lions, short-faced bears, wolves and scimitar cats. As a species, muskox outlived most of their Pleistocene contemporaries; although they suffered a setback in the 19th century, today close to 4,000 muskox live in Alaska.

Biologists with the Division of Wildlife Conservation have monitored muskox for decades, but in 2018 a position was dedicated to muskox research, based in Nome. Brynn Parr, who had been working in Juneau as the state’s permit biologist, was selected. Nome is on the Seward Peninsula, home to almost 2,100 muskox.

“As a department, we know a lot about animals like moose and caribou, but there’s a lot we don’t know about muskox,” said wildlife biologist and pilot Tony Gorn. He’s lived in Nome since 1997; he served as the area management biologist and is now the regional supervisor for Northwest Alaska.

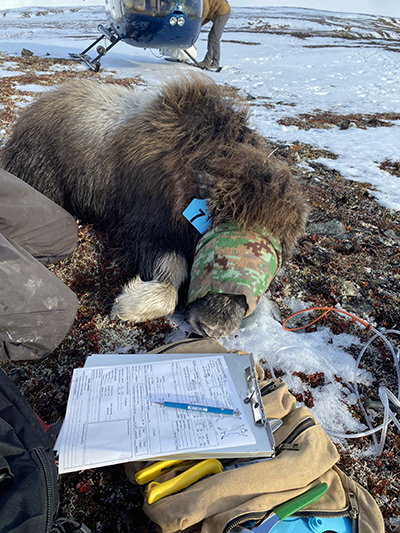

Parr moved north and embraced a challenging list of muskox questions. Collaborating with a team of colleagues, they’ve handled hundreds of muskox over the past few years, capturing more than 200 animals and equipped them with tracking collars. They’ve investigated kill sites to learn how and why muskox die, and collected tissue samples and hair to learn how nutrition, stress, and weather affect the animals’ health and population growth. Much of the research is groundbreaking, using new technology and tools, and biologists are fine-tuning their methods as they proceed.

“Muskox are such unique animals,” Parr said. “They’re so different from moose and caribou, and other ungulates up here. They’re a herd species, and there’s so much to learn.”

The nature of muskox

Parr described their temperament as pretty laid back. “If you really get up in their personal space they can get defensive, but they are not an aggressive animal,” she said. “It’s an almost daily occurrence to see muskox around Nome in summer.”

“They don’t look at people as a threat,” Gorn said. He sees them in his backyard, eating his rhubarb, his grass, and his wife’s flowers.

“We commonly watch muskox eating, resting and occasionally fighting in our backyard, just a few feet from our back deck,” he said. “You can hear the sounds they make … they are incredibly vocal. They roar, almost like a lion. There’s a bellowing sound they make that comes from deep within their chest. Every now and then they’ll really let out a roar, seems to be a communication, like “where is everybody at?”

They can be intimidating, he said, and although some people enjoy viewing muskox, some people dislike them.

“It’s not uncommon for Nome residents to see muskox just feet from their porch, and that can really catch people off guard whether it’s early in the morning or at the end of a long day,” he said. “It’s more troublesome during fall time when it’s dark during morning hours before school and work.”

For some people a bull muskox standing feet from their porch can be a scary and intimidating situation. As much as muskox are at peace with people, they dislike dogs. Gorn said over the years there have been some unfortunate muskox and dog encounters and some dogs have been killed, which is a hard thing to deal with. “It seems like people and muskox have a long-term love-hate relationship.”

Mating is in August and September, and the rut makes them less laid back. Bulls are mature at four years but don’t typically mate that young. One bull, typically a 5-7-year-old in his prime, will attempt to dominate and create a harem, breeding as many cows as he can. Others become satellite bulls or form bull-only groups. Parr said outside the rut, there doesn’t appear to be a hierarchy.

“Other than that, there doesn’t seem to be a dominant animal in a herd. One cow might lead one day, another on another day, and they follow this one or that one, no rhyme or reason to it that we’ve been able to discern.”

“You find groups of muskox that are only bulls, bachelor groups, some call them; or a solo bull, or a couple,” she said. “Cow groups might have a two- or three-year-old young bull.”

Cows are considered adult at three years and Parr said 70 to 80 percent will get pregnant, that rate is even higher once they reach four years of age. Young are born in late April, May and into June and adults are protective of the calves. Muskox are known for their tendency to group up or form a line and face a threat, their formidable bulk and hooked horns discouraging an attack. They also charge and flee as well. They aren’t quick over distance, but they can sprint.

“You don’t want to get too close or frustrate them,” Parr said. “They are these giant animals that take their time doing things, getting up, lying down, or feeding. But they are surprisingly agile if a predator comes around or if people or dogs come too close. If they’re near a road and a car comes by going too fast, that’ll get them running.”

The Nome animals are familiar with people, Parr said, but even animals not habituated to people are pretty tolerant. “Not unless you get close do they get up and all start facing you.”

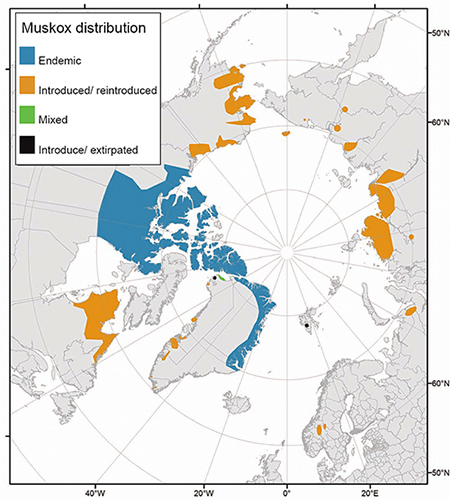

That behavior serves muskox well when bears and wolves approach – and presumably those prehistoric predators as well. It is ineffective against hunters with firearms, and over the 1800s and early 1900s muskox were extirpated from Alaska. A few dozen muskox from Greenland were transported to Alaska in the 1930s, and numbers grew steadily, especially on Nunivak Island (where they were first released to the wild) and on the Seward Peninsula, where Nunivak muskox were introduced in the early 1970s.

“A really healthy population”

One research project focuses on Nunavik Island muskox. The large, volcanic island sits off the Yukon-Kuskokwim Delta in southwest Alaska west of Bethel and 300 miles south of Nome. The island is home to 500-550 muskox.

“That population has no sign of slowing its growth, and it’s extremely productive,” Parr said. “There are no natural predators on the island. We use hunting to manage that population. They provide a way to see what a healthy, not-growth-limited population looks like.”

Hunters harvest about 85 muskox a year on the island and provide biologists with tissue samples. The animals’ nutritional condition is one focus, and the femur (legbone) offers clues. The amount of fat in the bone marrow of the femur is an indicator of overall condition – if it’s depleted an animal is starving or close to it. “Their bone marrow is extremely fatty, so they’re in good shape,” she said.

Hair from the shaggy coats supply a wealth of information. The long “skirt” hairs reach 400 mm (about 16 inches) in length – and knowing the growth rate for that hair (about four years) provides insight into years of that animal’s life. Stable isotopes of carbon and nitrogen can be detected, correlating to seasonal changes in diet. Reproductive hormones like progesterone are detectable and may indicate pregnancy. The presence of steroid hormones such as cortisol correlate to stress.

Shawna Karpovich is a state wildlife physiologist based in Fairbanks. She collaborates with researchers, applying this relatively new technology to learn about wolves, caribou, moose, seals and muskox. She flew out to Nome last summer and participated in a muskox field camp, but much of her work is in the lab, gleaning insights from seal whiskers, wolf claws, moose hooves and muskox skirt hairs. She recently acquired hair from 11 captive muskox with known reproductive histories, from the University of Alaska Fairbanks’ Large Animal Research Station, and she’s looking at hormone concentrations along the length of the hairs. She said identifying progesterone spikes associated with known pregnancies in captive animals will strengthen the ability to interpret what is measured in wild muskox.

Karpovich said the fresh green plant growth that wild muskox eat in the spring is more nitrogen-rich than their winter diet. When detected as stable isotopes of nitrogen in a length of hair, this graphs on a timeline as seasonal peaks and valleys.

Parr said events like a pregnancy or a stressful winter (identified via hormone fluctuations) can be sequenced on a timeline and correlated with other information. Comparing weather data – deep snow and harsh winter conditions – to cortisol levels can indicate how environmental conditions might affect the animals.

“The main purpose is to get baseline information,” she said. “What does a really healthy population look like? Down the road we could do a comparison study or look at trends in the same population.”

She added that Nunivak offers a great hunting opportunity; residents and nonresidents are allowed to hunt bulls through a draw hunt and cows through a registration hunt.

Population dynamics and mortality

A project on the Seward Peninsula looks at population dynamics and calves in particular. While the birth rate is good, there are not as many one- and two-year-old juvenile muskox as biologists expect to see. Researchers want to know how many calves are being born, when they are dying, and what they are dying from. Parr has looked at well over a hundred kill sites and currently has about 75 collars out. The collars are designed to expand as the calves grow and come off if they get too tight.

“We’re capturing and collaring neonatal, newborn calves and then tracking them over the first year or two – as long as the collar lasts,” she said. “Definitely the first year, and we’ve had good luck with collars lasting two years. When we detect a mortality signal we investigate.”

Lack of movement triggers the mortality signal, so the first question is, did the collar just fall off or did the calf die? “If it was a predator, we look for tracks, scat and other signs,” Parr said. “Wolves and bear leave a different kill site - bears will cache it, they scrape everything around the carcass into a mound. Wolves are more doglike, they dig a hole and put everything in it, or scatter things widely.”

Other ways to die

Bears are the primary predators of calves on the Seward Peninsula. Parr has not confirmed wolf mortalities in her work on the peninsula, but they are a main predator elsewhere. After bears, calves face an assortment of perils.

“Adults get irritated with calves and might hook them with a horn and toss them out of the way, and that could puncture the underside of the calf and get infected,” Parr said. “We had two (mortalities) we are pretty confident were wolverines, if they weren’t kills they were heavily scavenged by wolverines.”

Necropsies conducted by ADF&G wildlife veterinarian Dr. Kimberlee Beckmen confirmed the cause of death for two other calves.

“In 2019 we had a couple golden eagle kills, that was pretty fascinating,” Parr said. “We found the carcasses and sent them to Fairbanks. Kimberlee did the necropsy, she skins them out and does a thorough investigation, finds the exact puncture marks from talons. One eagle used its talons above the spine and punctured a lung; another one went after the face and crushed the calf’s skull with its talons.”

Muskox sometimes drift out to sea on ice floes, dooming them to drowning. One of the more unusual Advisory Announcements periodically issued reads: The Alaska Department of Fish and Game is opening a resident hunting season for muskoxen that are stranded on free-floating ice floes completely surrounded by salt water.

“It seems to happen every two or three years,” said Patrick Jones, the area biologist for the large region of southwest Alaska around Bethel that includes Nelson and Nunivak Islands. “The group size varies, usually one to four, there was one substantial group of about 35 one year.” Those animals were from Nunivak Island. Jones said muskox will wade up to their bellies, but they aren’t swimmers. “They don’t swim very well and not by choice,” he said.

Muskox have drowned during ice break-up on the Colville River, and in February 2011 an unusual wind-driven ocean tidal surge on the northwest edge of the Seward Peninsula pushed water and massive plates of sea ice ashore, overwhelming and killing a group of 52 muskox.

Tony Gorn, the biologist/pilot, knows of two incidents of muskox caught in avalanches, one involving 14 animals. Flying over mountainous terrain tracking collared animals, he’s seen them on really steep mountainsides.

“I’ve seen them places you wouldn’t believe they could be,” he said. “They’re big prehistoric goats.”

From the air he once saw tracks in the snow showing where a group of muskox had moved along a slope, then up on a ridge, and then out onto a cornice – which gave way, plunging them to their deaths.

If a muskox survives to adulthood, it can live eight to 12 years on average. Parr knows of a couple cows that are documented to be at least 18 and possibly more than 20 years old. A mature bull at the Musk Ox Farm in Palmer turned 24 this year.

Catching calves

An important component to answering muskox questions requires catching calves and tracking them over their early years. Alaska biologists have been collaring moose, bears, and caribou for years, but muskox present new challenges.

“When Brynn got the list of all these questions we had…she had to start from the ground floor, including, ‘How would you even catch a baby muskox?” Gorn said. “Muskox have a wide time period when they drop calves. Moose and caribou do a big baby dump, suddenly the landscape is covered with baby caribou. With muskox, it’s April, May and June, any time there. And unlike moose and caribou where there’s a mom and a neonate, with muskox there’s mom and a whole bunch of relatives. ‘How do we get in there and put on a collar or tag?’ Brynn has learned a lot over past years, working on methodology, trial and error.”

Parr and her colleagues have developed what’s likely the world’s best wild muskox calf capture method. She said they tried ground-based captures early in the project but found helicopter capture to be more efficient. This involves flying low over a group of muskox, which runs. The adults run ahead of the calves, then the helicopter drops down low over the calves and a biologist jumps off the skids and grabs one.

“The process is quick - about 16 seconds from time you first lay hands on it until you let it go,” she said. “You just slip on the collar, we don’t take blood samples or weigh them or anything like that. It’s about five minutes total: coming over the group in the helicopter, capturing, and then re-uniting calves with adults. We wear gloves and disposable leg coverings because the calves are pretty squirmy, and we want to minimize any human smell on the calves.”

Another step minimizes odors that might contribute to stress. “I go out a week or so before the capture and put some tundra in a Ziplock bag,” she said. “Blueberry and willow branches, moss and other vegetation, then put the collars in the bag so they smell like tundra.”

Two biologists are in the helicopter with the pilot, and only one jumps out. The second biologist is in the front seat taking notes, using a stopwatch to time the person handling the calf, and helping the pilot keep an eye on the rest of the herd. Roles switch as the day and season progress.

Parr said the adult muskox typically run away from the helicopter, but occasionally a mother will be super protective and turn back and charge. “So the helicopter is always staying right behind me, and I can quickly jump back on the skid and have the helicopter lift up in the event a cow charges. That’s only happened maybe a dozen times; the majority of the time, the mothers and the rest of the adults are moving away from us.”

More questions

As a management biologist, Gorn noticed a pattern of selective harvest by muskox hunters. Moose and caribou hunters tend to be opportunistic, he said, they’re unlikely to pass up a legal animal on opening day. Muskox hunters are more like Dall sheep hunters – they target big, mature males. This raised questions: What are appropriate harvest rates for that age class? How long do bulls live? Since muskox appear to be social animals - what is the role of mature bulls in the group of muskox? Against predators? Do we need to reserve some mature bulls in the population?

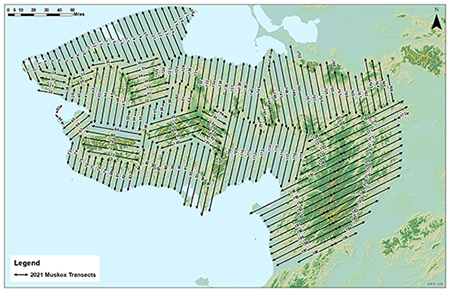

Flying surveys and observing muskox across the landscape raised other questions: Why do muskox move so much? And how might it relate to habitat?

“People think they just stand around out there,” he said. “There’s a lot of interchange from one group into another. They don’t make migrations like caribou, but they have the potential to move great distances. The Seward Peninsula covers 24,000 square miles, and our muskox seem to be all over the place. They might be down by Nome and then move north towards Kotzebue, then move from western to eastern portions of the game management units, or to different units. There are lots of questions about movements.”

Patrick Jones would like to know more about the movements of muskox in the area he manages around the Lower Yukon-Kuskokwim Rivers. There are around 200 muskox in that region (including areas upriver toward McGrath) and the population is growing; he said that if the population reaches the 350 to 400 range, it’s possible hunting could begin for a small percentage of bulls. “Before we get a hunt I’d like to understand their movements a little better,” he said. “We had one cow collared in the 1980s; she moved 150 miles north and then came back and was killed on Nelson Island in a legal hunt – she did this big 300 mile loop.”

He’s also curious about a discrepancy between pregnancy and birth rates on Nunivak Island. Counts in winter indicate 95 to 99 percent of the cows are pregnant, but in the following summer only 75 to 80 percent of the cows have calves. “What’s going on with the other 20 percent of the calves? Is it genetic defects? It’s not predators,” he said. “What is responsible for 20 percent failing to thrive? That might help us understand what’s going on in other places.”

The entire Alaska population is descended from just three dozen animals, a genetic bottleneck, and lack of genetic diversity could be a factor.

Gorn said biologists have developed a good understanding of how many moose a habitat can support but that’s not well understood for muskox. And there are other factors at play. Muskox are thriving on the Seward Peninsula, but further north, east of Kotzebue on the western North Slope, the numbers don’t compare. Why aren’t they doing better?

The Seward Peninsula is good muskox habitat, he said. It has the wide-bladed grasses and plants they prefer, and that other animals are not interested in. Muskox are not built for deep snow, and the peninsula has an abundance of relatively snow free areas; coastal areas, windswept areas that muskox need. But it’s dynamic.

“We continue to learn about changing climate,” he said. “There are warmer temperatures in the Bering Sea, sea ice is happening later, there’s open water instead of ice, schizophrenic snowfall, ice-on-snow and freeze-thaw cycles creating perhaps more difficult conditions for muskox. But muskox are survivors.”

Caribou and moose calving – “the big baby dump” – swamping predators

Muskox hunting – Nunivak Island

Subscribe to be notified about new issues

Receive a monthly notice about new issues and articles.