Salmon Shark

(Lamna ditropis)

Printer Friendly

Did You Know?

Salmon sharks are closely related to great white sharks.

General Description

The skin is dusky gray above and paler below with white markings. A strong swimmer, it has a wide tail that has a double keel (a second, short ridge running along the upper part of the lower lobe of the tail). A double keel is unusual among sharks; the only other double-keeled tail is on the closely related porbeagle shark. Salmon sharks can grow to over 10 feet long, but the average is usually in the 6.5-8 ft range. Maximum recorded weights of salmon sharks are in excess of 660 pounds. Males mature at 5 years of age and females at 8–10 years. Salmon sharks have long gill slits and possess large teeth.

Life History

Growth and Reproduction

After spending the summer in the northern part of their range, the salmon shark migrates south to breed. In the western North Pacific they migrate to Japanese waters whereas in the eastern North Pacific, the salmon shark breeds off the coast of Oregon and California. Males mature at 5 years of age and females at 8-10 years. Salmon sharks breed in late summer to early autumn. The internal developmental period in salmon sharks last 9 months. Developing embryos will consume unfertilized eggs in the womb. The female give birth to live young. Once the sharks are born, they are completely independent, and they have to fend for themselves

Feeding Ecology

As an apex predator, the salmon shark feeds on salmon, squid, sablefish, herring, walleye pollock, and a variety of other fish. They have been seen taking other prey including sea otters and marine birds. In 1998, Alaskan salmon sharks consumed twelve to twenty-five percent of the total annual run of Pacific salmon in Prince William Sound.

Migration

Salmon sharks are highly migratory, with segregation by size and sex, and with larger sharks ranging more northerly than young. Migration for the salmon shark is ultimately dependent on the concentration of the available prey species. Adult salmon sharks migrate alone or in loose groups of 30 to 40 individuals, following schools of Pacific salmon — including Sockeye (Oncorhynchus nerka), Pink (Oncorhynchus gorbusha), Chum (Oncorhynchus keta), and Coho (Oncorhynchus kisutch) — as they swim along the great arcs of current flowing off the coasts of northern Japan and the Kamchatka peninsula, the Aleutian Island chain, Alaska and British Columbia. There is an annual north-south movement of salmon sharks in both the eastern and western Pacific. Many salmon sharks feed in the coastal waters of the Gulf of Alaska, in particular Prince William Sound, home to Pacific salmon spawning grounds. Some of these sharks rapidly migrate southeast towards the west coast of Canada and the US; however, some remain in Prince William Sound and the Gulf of Alaska during winter months despite the colder temperatures.

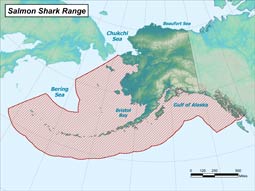

Range and Habitat

The salmon shark is widely distributed in coastal and oceanic environments of the subarctic and temperate North Pacific Ocean. Their preferred temperature range is 2.5 to 24 degrees Celsius. They range across the North Pacific from the Bering Sea and the Sea of Okhotsk to the Sea of Japan in the western Pacific, and from the Gulf of Alaska to southern Baja California, Mexico, in the eastern Pacific. This species is most common in continental offshore waters, from the surface down to a depth of at least 500 feet, but it has been known to come inshore - sometimes just beyond the breaker zone.

Status, Trends, and Threats

Status

The Salmon Shark occurs in the eastern and western North Pacific and its population appears to be stable and at relatively high levels of abundance. Currently there is no directed fishery in the Northeast Pacific, apart from a small sport fishery for the species in Alaska. Bycatch in the Northeast and Eastern Central Pacific appears to be at low levels and is not increasing at this point-in-time. Additionally, with the current ban on commercial fishing in Alaska state waters and fairly conservative sport fishing limits, it appears that the population is stable. By catch in the Eastern and Western Central Pacific has been significantly reduced since the elimination of the drift gillnet fishery and the population appears to have rebounded to its former levels. In addition, the most recent demographic analysis supports the contention that salmon shark populations in the Northeast and Northwest Pacific are stable at this time and it is assessed as Least Concern.

Threats

Overfishing is a main concern due to shark’s negative image as an abundant and low-value pest that avidly eats or damages valuable salmon and wrecks gear, which encourages fishers to kill it and add to mortality from finning and capture trauma. Knowledge of its biology is limited despite its abundance. Since its fecundity is very low, with no more than four to five pups per every two year reproductive cycle, and a slow maturation rate, this species probably cannot sustain current fishing pressure for extended periods. The North Pacific Fishery Management Council is currently considering closure of commercial fishing for sharks in Federal waters as no Federal Management plan exists specifically for sharks in the Gulf of Alaska and the Aleutian Islands. Currently, salmon sharks are allowed as bycatch, and are included in the commercial bycatch TAC (Total Allowable Catch) for Alaska Federal waters. Sport fishing regulations in Alaska include EEZ waters and are two sharks per person per year, one in possession at any time (one per day).

Fast Facts

-

Size

Maximum weight is over 660 pounds; Maximum length is over 10 feet, but the average is 6-8 -

Age

Maximum age is 25 years -

Range/Distribution

The salmon shark is widely distributed in coastal and oceanic environments of the subarctic and temperate North Pacific Ocean. -

Diet

Salmon sharks feed on sea otters, birds, salmon, squid, sablefish, herring, walleye pollock, and a variety of other fish -

Predators

Other sharks, humans -

Reproduction

Mating occurs in late summer to autumn. Females give live birth in the spring to 2-5 pups.

Did You Know?

- Salmon sharks are closely related to great white sharks.

- Salmon sharks have the ability to regulate their body temperature 14 to 20 degrees Fahrenheit above the ambient water temperature.

- Maximum age for salmon shark males is 25 years and for females 17 years.

- Salmon sharks are capable of speeds up to 50mph.

- Salmon sharks lack a swim bladder, but use their liver for buoyancy.

- A salmon shark’s liver can account for 25% of its total body weight.

- Developing salmon shark embryos will consume unfertilized eggs in the womb.

Uses

Commercial Fishery

The large numbers of salmon sharks observed in the mid-1990s in Prince William Sound gave rise to the idea of a commercial harvest. In 1996, a Cordova processor identified a market for salmon shark flesh. Using purse seine gear, fishermen were reported to have caught as many as 50 sharks in one set. However, the Alaska Board of Fish closed the commercial fishery and implemented strict regulations in the state sport fishery in 1997 due to a lack of biological information on salmon sharks.

Sport Fishery

Sport fishery charter companies have begun to specialize in salmon shark angling. Anglers looking for a new challenge have found it, with the salmon shark’s aggressive nature, large size, and fighting ability. Most charters operate out of Seward, Valdez, Cordova and Kodiak. Shark flesh has a high urea content, so bleeding and gutting must take place immediately. Properly processed salmon shark flesh is said to taste like swordfish, and freezes well.

Processing

The flesh is used for human consumption, where it is processed into various fish products. In Japan, the hearts are consumed as sashimi. Its oil, skin (for leather), and fins (shark fin soup) are utilized also.

Management

The Alaska State Constitution establishes, as state policy, the development and use of replenishable resources, in accordance with the principle of sustained yield, for the maximum benefit of the people of the state. In order to implement this policy for the fisheries resources of the state, the Alaska Legislature created the Alaska Board of Fisheries (BOF) and the Alaska Department of Fish and Game (ADF&G).

The BOF was given the responsibility to establish regulations guiding the conservation and development of the state’s fisheries resources, including the distribution of benefits among subsistence, commercial, recreational, and personal uses. The ADF&G was given the responsibility to implement the BOF’s regulations and management plans through the scientific management of the state’s fisheries resources. Scientific and technical advice is also provided by the ADF&G to the BOF during its rule-making process. The separation of rule-making and inseason management responsibilities between these two entities is generally regarded as contributing to the success of Alaska’s fisheries management system.

The ADF&G’s fishery management activities fall into two categories: inseason management and applied science. For inseason management, the department deploys a cadre of fishery managers near the fisheries. These individuals have broad authority to open and close fisheries based on their professional judgment, the most current biological data from field projects, and fishery performance.

Get Involved

- Alaska Board of Fisheries

- Fish and Game Advisory Committees

- ADF&G Internships

- Report Salmon Shark Sightings (PDF 216 kB)