Northern Flying Squirrel

(Glaucomys sabrinus yukonensis)

Printer Friendly

Did You Know?

The northern flying squirrel is strictly nocturnal, and is only active about an hour after sunset for a couple hours, and again about an hour or two before sunrise.

General Description

The northern flying squirrel (Glaucomys sabrinus yukonensis) is a gliding (volplaning) mammal that is incapable of true flight like birds and bats. There are 25 subspecies across North America with Interior Alaska being the most northern and western limit of the species' range. The generic name, Glaucomys, is from the Greek glaukos (silver, gray) and mys (mouse). Sabrinus is derived from the latin word sabrina (river-nymph) and refers to the squirrel's habit of living near streams and rivers.

There are several subspecies of northern flying squirrel in Alaska. The subspecies Yukonensis is the most widespread in Alaska and is found throughout the Interior. Zaphaeus is the subspecies most widespread in Southeast Alaska. Griseifrons is a subspecies found only on Prince of Wales and a few closely adjacent islands. Another subspecies, Alpinus, is found in B.C. and the Yukon and is also found in Juneau area — it is believed that animals came down the Taku River corridor and the dispersed.

Adult flying squirrels average 4.9 ounces (139 g) in weight and 12 inches (30 cm) in total length. The tail is broad, flattened, and feather-like. A unique feature of the body is the lateral skin folds (patagia) on each side that stretch between front and hind legs and function as gliding membranes. This squirrel is nocturnal and has large eyes that are efficient on the darkest nights. Eye shine color is a distinctive reddish-orange. Flying squirrel pelage is silky and thick with the top of the body light brown to cinnamon, the sides grayish, and the belly whitish.

Life History

Growth and Reproduction

Flying squirrels in Alaska may breed anytime from March to late June, depending on length and severity of the winter. The female can breed before 11 months of age and give birth at about 1 year of age. Gestation requires about 37 days, so the young are born from May to early July. One litter of two per year is probably the usual case for Alaska, but they are known to have litters ranging from one to six in other parts of their range.

At birth, the young flying squirrel (nestling) is hairless, and its eyes and ears are closed. Development is slow in comparison with other mammals of similar size. Their eyes open at about 25 days, and they nurse for about 60 to 70 days. By day 240, the young are fully grown and cannot be distinguished from adults by body measurements and fur characteristics. Mortality rate for flying squirrels 1 and 2 years old is about 50 percent, and few live past 4 years of age. Complete population turnover can occur by the third year.

Feeding Ecology

The flying squirrel is omnivorous. While little is known about its diet in Alaska, the food it consumes in other parts of its range include mushrooms, truffles, lichens, fruits, green vegetation, nuts, seeds, tree buds, insects, and meat (fresh, dried, or rotted). Nestling birds and birds' eggs may also be eaten.

Feeding areas preferred by flying squirrels may be in either young or old forests. Dried fungi cached in limbs by red squirrels are sometimes stolen by flying squirrels.

Those observed foraging in the wild in Interior Alaska ate mushrooms (fresh and dried), truffles, berries, tree lichens, and the newly flushed growth tips on white spruce limbs. In spring, summer, and fall the diet is mostly fresh fungi. In winter it's mostly lichens. Flying squirrels are not known to cache fungi for winter in Alaska, but they are known to do so elsewhere in their range. Witches' brooms and tree cavities would be likely places to find their caches.

Flying squirrels probably get water from foods they eat and rain, dew, and snow. Constant sources of free water (lakes, ponds, and watercourses) do not appear to be a stringent habitat requirement.

Hibernation

About November or December, when temperatures begin to drop sharply, flying squirrels move out of tree cavities and into brooms (clumps of abnormal branches caused by tree rust diseases). In the coldest periods of winter, they form aggregations of two or more individuals in the brooms and sleep in torpor.

Range and Habitat

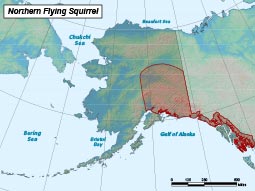

The northern flying squirrel occurs throughout forested areas of Alaska.

Flying squirrels require a forest mosaic that includes adequate denning and feeding areas. Den sites include tree cavities and witches' brooms. Tree cavities are most numerous in old forests where wood rot, frost cracking, woodpeckers, and carpenter ants have created or enlarged cavities. Witches' brooms, clumps of abnormal branches caused by tree rust diseases, are the most common denning sites of flying squirrels in Interior Alaska.

In Interior Alaska, most brooms and cavity entrances have southerly exposures. Nests in cavities are usually located about 25 feet above the ground but may range between five and 45 feet. Flying squirrels excavate chambers in witches' brooms and line them with nesting materials. A dray nest is a ball-like mass of mosses, twigs, lichens, and leaves with shredded bark and lichens forming the lining of the chamber. Flying squirrels build drays entirely by themselves or modify the nests of other species (e.g., bird nests, red squirrel nests). The dray is usually positioned close to the trunk on a limb or whorl of branches with its entrance next to the trunk. Most drays in Alaska are probably conifers.

In a year's time, a flying squirrel in Interior Alaska may use as many as 13 different den trees within 19.8 acres (8 ha). On a night foray, a squirrel may travel as far as 1.2 miles (2 km) in a circular route and be away from its den tree for up to 7 hours. It may change den trees at night and move to different ones more than 20 times over a year, staying in each for a varying numbers of days. Den trees with brooms are used more than twice as much as trees with cavities.

Fairly dense, old closed-canopy forests with logs and corridors of trees (especially conifers) that are spaced close enough to glide between are needed for cover from predators. High quality flying squirrel habitat can be a community mosaic of small stands of varying age classes in which there is a mix of tall conifers and hardwoods. Riparian zones provide excellent habitat in all coniferous forest associations.

Status, Trends, and Threats

Status

- NatureServe: G5

- IUCN: LC (Least Concern)

Threats

Logging for house logs, wood for fuel, and lumber, can have devastating effects on flying squirrel populations if clearcut size is too large or if some scattered tall conifers in large cuts are not retained as cover and for travel across the open spaces.

Fast Facts

-

Size

Weight: 75 to 140 g

Length: 275 to 342 mm -

Lifespan

1–4 years -

Range/Distribution

Throughout forested areas of Alaska. -

Diet

Mushrooms, truffles, lichens, fruits, green vegetation, nuts, seeds, tree buds, insects, and meat (fresh, dried, or rotted). -

Predators

Owls, hawks, and carnivorous mammals prey on flying squirrels. Primary predators are probably the great horned owl, goshawk, and marten due to their common occurrence and widespread range in Alaska's forests. -

Reproduction

Breed once per year. Females give birth to a litter of one to six offspring, where two is generally the average.

Did You Know?

- Individual Glaucomys sabrinus aggregate into single-sex groups for warmth during winter.

- The northern flying squirrel is strictly nocturnal, and is only active about an hour after sunset for a couple hours, and again about an hour or two before sunrise.

- Studies of flying squirrel population densities on Prince of Wales Island indicate two to four squirrels per hectare (2.4 acres) — comparable to densities of red squirrels in other parts of Alaska (there are no red squirrels on POW Island).

Uses

Flying squirrels are important to forest regeneration and timber production because they disperse spores of ectomycorrhizal fungi like truffles. Truffles are fruiting bodies of a special type of fungus that matures underground. They are dependent upon animals to smell them out, dig them up, consume them, and disperse their spores in fecal material where the animal travels. The animal serves to inoculate disturbed sites (e.g., clearcuts, burned areas) with mycorrhizae that join symbiotically with plant roots and enhance their ability to absorb nutrients and maintain health. The flying squirrel's ecological role in forest ecosystems, therefore, gives it economic value. In addition, they may be important prey for a variety of hawks, owls, small carnivores, and furbearers like marten, lynx, and red fox. Many Alaskans value flying squirrels just for their interesting habits and aesthetic qualities.

Management

Management should include retention of other squirrel species in shared habitats. Snags with woodpecker holes or other natural cavities and coniferous trees with witches' brooms must also be maintained in managed forests in order to provide adequate habitat for flying squirrels.

More Resources

General Information

- Northern Flying Squirrel — Wildlife Notebook Series (PDF 51 kB)

- Alaska Fish and Wildlife News article

Flying Squirrels - Night Gliders are More Common than People Realize