Commercial Salmon Fisheries

Southeast Alaska & Yakutat Research: Taku River Salmon Research

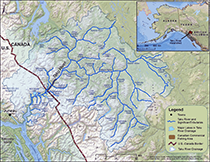

Figure 1. — Click for more Info

Figure 2. — Click for more Info

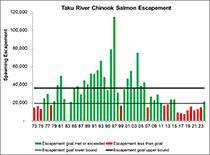

Figure 3. — Click for more Info

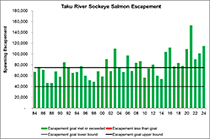

Figure 4. — Click for more Info

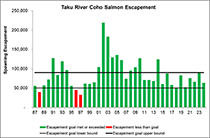

Figure 5. — Click for more Info

Figure 6. — Click for more Info

Figure 7. — Click for more Info

Figure 8. — Click for more Info

Figure 9. — Click for more Info

Figure 10. — Click for more Info

Figure 11. — Click for more Info

Figure 12. — Click for more Info

Figure 13. — Click for more Info

Introduction

The Taku River is a large, glacial, transboundary watershed originating in northwest British Columbia and draining into Taku Inlet about 25 kilometers (15 miles) east of Juneau, Alaska (Figure 1). The Taku River has runs of all five species of Pacific salmon, including the largest run of Chinook salmon in Southeast Alaska and northern British Columbia as well as some of the larger runs of sockeye and coho salmon in the region. Due to the salmon production capability of the Taku River drainage, it is no surprise it has been a significant contributor to numerous fisheries in the region over the years. Prior to statehood, historical harvest records for Taku River Chinook salmon are spotty but it is likely that sport fishers have targeted this stock for over a century. Commercial fisheries, mainly drift gillnet fisheries, have harvested Taku River salmon near the mouth of the river since the late 1800s with documentation of a "saltery" in Taku Inlet before 1900 and the opening of two canneries in the inlet in 1900. Tlingit people residing in coastal and inland communities of modern-day Alaska and the Canadian provinces of British Columbia and Yukon have relied on Taku River salmon since time immemorial.

Taku River salmon stock assessment was initially implemented before statehood by the Alaska Department of Fisheries in 1951, two years after being created by the Territorial Legislature. Salmon stock assessment work in 1951 originally focused on Chinook salmon (Valley of the Kings on Vimeo), but included sockeye, coho, chum, and pink salmon in future years. Several aspects of the salmon stock assessment work conducted in the 1950s are still in place today and include sampling adult salmon using fish wheels (Figure 2) near Canyon Island (approximately 4 kilometers below the U.S./Canada border) and sampling adult Chinook salmon by foot and with a weir on the Nakina River (Figure 3). Many of the methods used to assess the runs of adult salmon to the Taku River did not persist through the 1960s, though they were resumed in the early 1970s and have expanded and been bolstered since.

The aerial survey program to assess the abundance of large (essentially 28 inches and greater in length) Chinook salmon that is still used today was standardized in 1973, though aerial surveys go back to the 1950s. Current survey methods include counting large Chinook salmon using a helicopter flown at low speeds and elevation over five of the most productive Chinook salmon spawning grounds in the drainage (Nahlin, Dudidontu, and Nakina Rivers and Kowatua and Tatsatua Creeks; Figure 4). The carcass weir on the Nakina River that was used before statehood has been operated annually since 1973 to assess Chinook salmon returns. Two fish wheels in the vicinity of Canyon Island in the lower river have been operating each season since 1984 (Figure 5). The fish wheels are used for capturing adult Chinook, sockeye, and coho salmon that return each season for stock assessment purposes. The fish wheels were initially brought back to assess the run of adult sockeye salmon using mark-recapture methods in 1984 but later included coho (1987-present) and Chinook (1989, 1990, 1995-present) salmon.

Taku River salmon stock assessment for Chinook, sockeye, and coho salmon, along with the terminal fisheries that harvest these stocks, fall under the purview of Chapter 1 of the Pacific Salmon Treaty. The treaty commits Canada and the U.S. to conservation and allocation obligations for salmon originating in the Canadian portions of the Taku River. To fulfill treaty commitments, Canada and the U.S. maintain a highly cooperative stock assessment program among staff from the Taku River Tlingit First Nation (TRTFN), Department of Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO), and the Alaska Department of Fish and Game (ADF&G). Annual stock assessment information facilitates abundance-based management by the U.S. and Canada and includes preseason forecasts, inseason run abundance, escapement estimates, terminal harvest estimates, and postseason run reconstructions. Smolt abundance and marine survival are also estimated for Chinook and coho salmon. This stock assessment information is used by both countries to manage the Taku River salmon stocks responsibly and to provide maximum sustainable yield based on biological escapement goals.

Study Area

The Taku River drainage (17,000 square kilometers) is larger than the state of Connecticut in area, with roughly 90% of the watershed located in British Columbia, Canada. The Taku River's roughly 90 kilometer length is glacially-fed with the U.S./Canada border bisecting the river approximately 30 kilometers above the estuary where the river divides the rugged Coast Mountains. The river terminates in Taku Inlet just east of Juneau, Alaska. The Taku River splits (Figure 6) into two main branches, the Inklin and Nakina Rivers, approximately 50 kilometers above the international border. As the river travels north and east away from coastal influence, the biome quickly changes from a temperate maritime environment typical of Southeast Alaska to a much drier boreal clime typical of interior areas of similar latitude.

Adult Abundance

Chinook

Adult salmon start to return each spring to the Taku River by April when Chinook salmon begin to migrate into the river below the ice and before the river is open to boat traffic. Chinook salmon generally pass the lower river near the international border from April through mid-July each season. Since 1973, Taku Chinook salmon spawning abundance has ranged from 7,271 (2018) to 114,938 (1997) and averaged around 32,000 large Chinook salmon (Figure 7). Escapement estimates for large Chinook salmon were generated in 1973–1988, 1991–1994, 1998, 2011–2013, and 2021 using expanded aerial counts. Escapement estimates were generated through a two-event mark-recapture experiment in all other years starting in 1989 and is the preferred estimation method when sufficient data is available.

Chinook salmon are captured for stock assessment purposes in the lower Taku River each spring as fish migrate upriver to spawning habitat. A drift gillnet and two fish wheels in the vicinity of Canyon Island are used to capture migrating fish (Figure 8). All Chinook salmon captured are sampled for age, sex, and length and tagged with a uniquely numbered spaghetti tag inserted in the dorsal musculature of the fish. From late July through mid-September U.S. and Canadian crews sample Chinook salmon in six of the major spawning tributaries (Nahlin, Dudidontu, Nakina Rivers and Tseta, Kowatua, and Tatsatua Creeks) across the Taku drainage, examining all fish for marks and tags that were applied in the lower river. The combined tagging efforts below the U.S./Canada border, and the recapture efforts spread across the drainage above the border, are used to estimate escapement annually.

Sockeye

Returning adult sockeye salmon arrive in the lower river in late-May to early-June and continue to run through the end of September, with the midpoint of the run inriver by late July. Since 1984, Taku sockeye salmon spawning abundance has ranged from 33,104 (1987) to 155,192 (2021) and averages around 77,000 fish (Figure 9). The average harvest rate from 1984 to present for returning Taku River sockeye salmon is 55%, with the majority of the fish harvested by the District 111 drift gillnet fleet and the Canadian inriver commercial fishery. Like Taku River Chinook and coho salmon, sockeye salmon escapement is estimated annually using a mark-recapture experiment.

For the marking event of the mark-recapture experiment, sockeye salmon are captured in the fish wheels near Canyon Island each season as they migrate upriver. Sockeye salmon captured in the fish wheels are sampled for age, sex, and length and tagged (≥ 350 millimeters as measured from mid-eye to folk of tail) with a uniquely numbered spaghetti tag. The recapture event to estimate escapement occurs just above the international border where fish harvested in the Canadian commercial fishery are inspected for marks by DFO staff. The mark-recapture data is shared daily by U.S. and Canadian staff which allows for generation of weekly bilateral estimates of abundance that managers on both sides of the border incorporate into fishery management decisions.

Unlike Chinook salmon that return to the Taku River each season and spawn predominately in discrete, clear or lightly occluded glacial tributary reaches, sockeye salmon spawn in several lakes, rivers, and streams across much of the Taku drainage. The largest producing lakes are King Salmon, Kuthai, Little Trapper, and Tatsamenie Lakes. Though Taku River sockeye salmon are managed as an aggregate stock for PST purposes, DFO and TRTFN staff operate either a picket style weir or video weir on all four of the major sockeye salmon producing lakes to gather additional stock specific information on returning fish (Figure 10). There is no specific stock assessment for river-type sockeye salmon on the Taku River. The ratio of lake-type to river-type sockeye salmon that return annually to the Taku River can vary significantly from year to year. Through several seasons of radiotelemetry studies and genetic sampling, it has been determined that the ratio of fish can be over 70% either lake-type or river-type spawners in one season, but that ratio can flip from season to season.

Coho

Coho salmon are typically a month behind sockeye salmon and arrive in the lower Taku River around late June and peak in late-August to early-September each season. Since 1987, Taku coho salmon spawning abundance has ranged from 32,345 (1997) to 219,360 (2002) and averages around 87,000 fish (Figure 11). The average harvest rate from 1992 to present for returning Taku River coho salmon is 45%, with on average half the harvest coming from terminal fisheries. These terminal fisheries primarily consist of the Juneau sport fishery, the District 111 commercial drift gillnet fishery, and the Canadian inriver commercial fishery. Taku River coho salmon can also see large portions of annual harvest in the Southeast Alaska troll fishery. Taku River coho salmon escapement is also estimated annually using a mark-recapture experiment.

The annual mark-recapture experiment for returning Taku River coho salmon is very similar to sockeye salmon in which fish are captured using fish wheels and are sampled for age, sex, and length and tagged (≥ 350 millimeters as measured from mid-eye to fork of tail) with a uniquely numbered spaghetti tag. The recapture event also takes place just above the international border in the Canadian commercial fishery as well. If effort from inriver Canadian commercial fishery stops before the end of September, which simultaneously stops the recapture event, an assessment fishery is put in place to provide recaptures through the month. As with sockeye salmon, weekly bilateral estimates of abundance are generated that U.S. and Canadian fishery managers incorporate into fishery management decisions inseason.

Juvenile Abundance

Juvenile tagging studies for Chinook salmon were initiated briefly in the late 1950s and again in the late 1970s into the early 1980s in the attempt to learn more about marine harvest patterns of Taku River Chinook salmon. Cooperative studies among ADF&G, DFO, and TRTFN have occurred to estimate the abundance of juvenile Chinook and coho salmon in the Taku River drainage since 1991 and 1993, respectively. These juvenile tagging studies provide fishery researchers and managers with estimates of abundance, marine survival, and marine harvest which combined with adult stock assessment data allows for complete run reconstructions.

Chinook and coho salmon smolt outmigrate from the Taku River mainly in April and May each spring. During this time, crews capture Chinook and coho salmon smolt using minnow traps baited with disinfected salmon eggs and beach seines (Figure 12). Smolt capture is focused in mainstem habitat of the Taku River roughly ten miles on either side of the international border. After smolt are captured, they are transported back to camp and are anesthetized, marked, tagged, and held for 24 hours to assess retention of coded wire tags and ensure they are healthy prior to release (Figure 13). Most coho smolt are captured using minnow traps in April through early May, and as water temperatures and depth increase during May, larger numbers of outmigrating Chinook smolt are encountered and beach seines are used as the primary method of fish capture.

Information of the fraction of fish marked with adipose fin clips is used in combination with adult sampling information to estimate smolt abundance. In addition, the fraction of these fish possessing valid coded wire tag released in the Taku River is used to estimate adult harvests in the various marine commercial and sport fisheries. The estimated harvest of a particular parent (brood) year is coupled with estimates of the parent year spawning abundance to reconstruct the complete return. Finally, capture rates in the marine fisheries for fish possessing coded wire tags aid in fishery management and are used as inseason predictors of run strength and harvest rates.

Data collected from coded wire tag recoveries, when combined with adult spawning abundance estimates, allow parent year production estimates, including estimates of marine harvests, smolt abundance, and marine survival of the Taku River Chinook and coho salmon.

Selected Publications

Chinook

- Smolt abundance and adult escapement of Chinook salmon in the Taku River, 2022 (PDF 3,020 kB)

- Migration, tagging response, and distribution of Chinook salmon returning to the Taku River, 2018. (PDF 1,854 kB)

- Spawning abundance of Chinook salmon in the Taku River from 2008 to 2010 (PDF 2,461 kB)

- Spawning Abundance of Chinook salmon in the Taku River from 1999 to 2007 (PDF 14,413 kB)

- Spawning Abundance of Chinook Salmon in the Taku River in 1998 (PDF 510 kB)

- Spawning Abundance of Chinook Salmon in the Taku River in 1997 (PDF 1,906 kB)

- Spawning Abundance of Chinook Salmon in the Taku River in 1996 (PDF 2,006 kB)

- Spawning Abundance of Chinook Salmon in the Taku River in 1995 (PDF 2,145 kB)

- Abundance of the Chinook Salmon Escapement in the Taku River, 1989 to 1990 (PDF 299 kB)

- Optimal Production of Chinook Salmon from the Taku River through the 2001 Year Class (PDF 635 kB)

- Optimal production of chinook salmon from the Taku River (PDF 635 kB)

Sockeye

- Migration, tagging response, distribution, and inriver abundance of Taku River sockeye salmon, 2022 and 2023. (PDF 1,423 kB)

- Tagging response, distribution, and migration, of Taku River sockeye salmon, 2020. (PDF 3,191 kB)

- Migration, tagging response, and distribution of Taku River sockeye salmon, 2019. (PDF 7,068 kB)

- Mark-recapture studies of Taku River adult sockeye salmon stocks in 2012 and 2013 (PDF)

- Mark-recapture studies of Taku River adult sockeye salmon stocks in 2010 (PDF)

- Mark-Recapture Studies of Taku River Adult Sockeye Salmon Stocks from 1998 to 2002 (PDF)

- Mark-recapture studies of Taku River adult salmon stocks in 1995 (PDF 5,344 kB)

- Adult mark-recapture studies of Taku River salmon stocks in 1989. (PDF 3,231 kB)

Coho

- Smolt abundance and adult escapement of coho salmon in the Taku River, 2022 (PDF 1,795 kB)

- Estimates of a Biologically-Based Spawning Goal and Biological Benchmarks for the Canadian-Origin Taku River Coho Stock Aggregate (PDF)

- Production of Coho Salmon from the Taku River, 1996-1997 (PDF 1,954 kB)

- Production of Coho Salmon from the Taku River, 1995-1996 (PDF 2,569 kB)

- Production of Coho Salmon from the Taku River, 1994-1995 (PDF 2,985 kB)

- Production of Coho Salmon from the Taku River, 1993-1994 (PDF 3,000 kB)

- Production of Coho Salmon from the Taku River, 1992-1993 (PDF 2,906 kB)

- Production of Taku River Coho Salmon, 1991-1992 (PDF 3,173 kB)

- Production of Coho Salmon from the Taku River, 1997-1998 (PDF 1,607 kB)

- Production of Coho Salmon from the Taku River, 1998-1999 (PDF 2,953 kB)

- Production of coho salmon from the Taku River, 1999-2003 (PDF 706 kB)

- Production of coho salmon from the Taku River, 2003–2007 (PDF 4,935 kB)